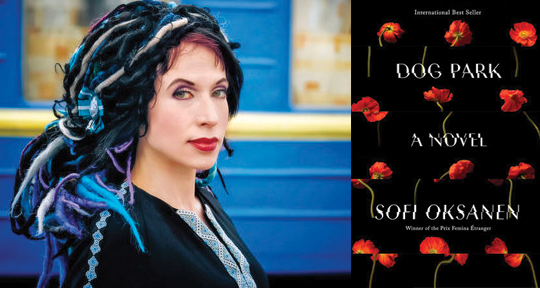

Dog Park by Sofi Oksanen, translated from the Finnish by Owen F. Witesman, Knopf, 2021

A woman sitting on a park bench, pretending to read to avoid unwanted conversation while gazing at people playing with their dogs in the park. Translated from the Finnish by Owen F. Witesman, Sofi Oksanen’s novel Dog Park begins with this image redolent of solitude, set to unravel the narrative that flickers between two main time-spaces filled with sociohistorical references. The year that marks the first scene of the novel is 2016, two years after the break of the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war over Crimea and the Donbas region of Ukraine. Afterwards, the author guides us back and forth between the 1990s–2000s and 2016, continuously indicating to which year and location each chapter belongs. The invisible third spaciotemporal layer would be, of course, the readers’—who are inevitably made aware that the weight of the narrative depends on their own year and location. In Dog Park, Oksanen deftly interweaves the lives of Ukrainian women in the mid-2000s, a happy Finnish family in 2016, and readers in 2021 through overlaps of intentions, memories, and citizenships.

So the story begins. The identity of the woman sitting on the park bench is gradually revealed. Then the narrative flashes back to the late 2000s when she matches potential donors to desiring would-be-parents who shop the eggs under the premise that they are genetically infallible, meaning their producers should be free of not only heritable diseases but also physical unattractiveness, mental health issues in the family, and experience of poverty. Our protagonist, Olenka, jumps into this line of business after failing to make a living as a fashion model in the West, having been desperate to leave her home in Snizhne, where her mother and aunt run a small poppy farm that produces compote (homemade heroine). She contrives a new life in Dnipro, which allows her much-desired urban extravagance and upward social mobility. In the process, Olenka gets reintroduced to a long-time family friend, contacts the Kravetes, a family from Ukraine’s upper echelon, and meets “you,” who is constantly addressed throughout the novel. How Olenka’s plans are laid out, at times successfully and at others catastrophically, keeps the narrative going until the end. There’s not a single moment when the novel leaves readers sure of what’s happened, happening, or going to happen. At the end of almost every chapter begins a new suspense, usually marked by Olenka’s gradual revelation of an unmentioned aspect of the main narrative. These mini-plot twists—a death, a birth, or a warped relationship—turn the pages to the very end.

The main narrative of Dog Park extends from three key concepts: social turmoil of post-Soviet Ukraine, the economic codependency between the peripheral East and the central West, and commodification of women’s bodies amid such social and economic unrest. Olenka’s family moved from Tallinn, Estonia, to Snizhne, Ukraine after the collapse of the Soviet Union, mostly for her father’s dream of scoring big in his rural hometown by operating kopanka, an illegal and hazardous coal mine. Olenka grows up to despise Snizhne because of her traumatic memory and the label of poverty associated with it. She strives to leave the town both physically and mentally, only to find herself unable to ever return even if she wanted. Having lived in Finland for a decade, Olenka keeps comparing the lives of the Finns with her own and of those who were close to her in Ukraine. The carefree lives in the safe, affluent states of the West are illustrated in stark contrast to the disorderly, corrupted, and murderous lives in Ukraine, mostly to emphasize her contempt toward her air-polluted home of Snizhne. Americans and West Europeans disguising themselves as tourists to buy eggs, Finns who can afford to be sympathetic to an immigrant woman, and the cutthroat yet glamorous fashion industry in Paris are sources and traces of Olenka’s desire for a stable life that once seemed to be within her reach. Deliberately retained in Witesman’s English translation, Oksanen’s use of Ukrainian terms and Slavic slang demonstrates the unrelenting grip of Olenka’s origins, which she can neither reclaim nor be completely rid of at any point in the narrative.

The question of the role of women’s bodies is central to Dog Park. When a system fails, along with its sustaining ideology and its people’s lives, how does the unstable society make use of its minority population, in this case women? “Selling” them is one easy answer, both history and the novel seem to tell us. All career paths laid out before Olenka focused on her physicality as a woman: modeling, commercial marriage, surrogacy, and egg donation. When she is promoted to coordinator, she becomes the one to select candidates for egg donation, scrupulously investigating and fabricating the girls’ backgrounds and assessing their commercial value to accommodate the Western clients’ eugenicist demands. The title Dog Park rings an ominous tone at this juncture, in which readers are faced with the casual gene-shopping that is all too familiar through dog breeding. At the beginning of the novel, Olenka watches the happy Finnish family, impressed by their perfect appearance: “Even the mad dash of their schnauzer when they let it free was a flaw-less performance. Its rare white coloration attracted attention; at dog shows, it always won.” Such an uninhibited desire for delusive perfection is repeatedly verbalized by many characters throughout the novel, from those at the dog park to the catalog of smiling women posing for selection as egg donors. Here, women are either easily replaceable commodities with product descriptions or those on the consumer side of the exchange. People in the periphery continuously provide goods or services to their urban, Western, and wealthier clientele. These consumers don’t seem to care if the donors are humans trying to sustain their lives, unless they disturb the comfort of their clients. The eggs the women produce are just one category of items the clientele can purchase, suggesting the faintness of each donor’s humanity.

Sitting on the park bench, Olenka watches not dogs but a beautiful, however illusory, human family. She imagines the child’s upbringing, supposedly ideal under Finland’s famous welfare system, and how different that would be from her own in Snizhne. This woman who blends in with the park’s peaceful landscape is one who has lost everything. What happened to the numerous egg donors is kept unsaid, except for a few cases including her own. This suspense adds to the emotional burden readers must bear from the beginning as this likely dystopia unfolds. Through the tales of the dead, the unborn, and want-to-be mothers, Oksanen’s robust storytelling brings to the fore in this ruminative thriller the capitalization of women’s bodies, on either side of supply and demand, happening then and now—in 2006, in 2016, and 2021.

Megan Sungyoon translates between languages and across genres. After graduating from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a BFA thesis installation of text, video, and sound, Sungyoon lived in New York from 2018 to 2020 to pursue an MFA in poetry and literary translation at Columbia University. Sungyoon’s work has appeared in The Toad Press International Chapbook Series, Asymptote, Columbia Journal, SAND Journal, The Margins, and Hypertext Review.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: