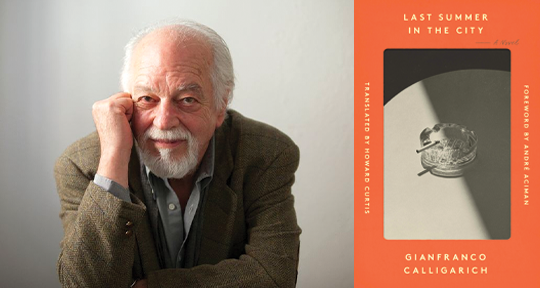

Last Summer in the City by Gianfranco Calligarich, translated from the Italian by Howard Curtis, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021

Gianfranco Calligarich’s Last Summer in the City tells the deceptively simple story of a young man drifting through life, searching for romance and success amidst the urban swelter. Newly employed at a medical-literary magazine, narrator Leo Gazzara moves from Milan to Rome—only to be fired a year later due to the publication’s imminent bankruptcy. As he bounces around various jobs and other heartless endeavors, brooding resignation and lethargy permeate Leo’s world; his life, utterly devoid of excitement, becomes simply a series of events to be accepted and passed through in their procession. For the most part, he is a drifter—a flâneur without the poetic possibilities of transcendence. Unambitious and apathetic as he might appear to be, however, the story of Leo is nevertheless one of delicate beauty that imparts the prevalent, existential angst that defined a generation of young men amidst the Italy of the 70s.

In the vein of postwar Italian neorealism, Calligarich spends much of the text on bringing texture and illustration to the humble details of everyday life, and the resulting cinematic effect can likely be referred back to the author’s experience as a screenwriter. Leo’s story counteracts the adulation of glamour and happiness in Fascist propaganda, which holds little to no concern for the personal difficulties of everyday life—boredom, failure, or grief. Instead of telling the simple, customary story of a powerful and desirable man amidst a cosmopolitan enchantment, Last Summer in the City presents a marginalized individual’s quotidian, melancholic tale in a provincial setting. The quiet, understated prose emanates an almost diaristic intimacy into the narrator’s mind, providing an avenue to access his inner vacuum of emptiness, and the terrible simplicity of his apathy.

Instead of actively involving himself in his surroundings, Leo sets out to stay on the sidelines and observe. But his desire to avoid the rat race instead culminates in the inability to connect with anything around him. Amongst the prominent evidence of this solitude is when Leo talks about his relationship with his father: what dominates it is, in fact, silence. His father responds with silence to Leo’s failure to succeed (in comparison to his elder sisters’ white-collar marriage), with the void stretching to engulf the two even when Leo leaves Milan for Rome. In a heavy instant, this stoic disposition is passed down from father to son: “We looked at each other in silence, as usual, but I realized that we were saying good-bye.”

While Leo is able to establish casual friendships in Rome, they all, in turn, leave the city one after another, handing down their possessions to Leo. Eventually, these leftovers make up the entirety of Leo’s possessions—composing, in their inconsistent nature, a synecdoche of Leo himself: a “leftover” person who is the exact opposite of society’s definition of success, having neglected the mandate to “graduate, get married, make money.” Essentially alone, Leo posits “we are what we are not because of the people we’ve met but because of those we’ve left.” As such, Leo’s position is one of the other people’s consequences, dejected at the margin of the Italian society.

The tides of Leo’s unspectacular life are narrated without any significant emotional resonance. When Leo first meets his future girlfriend, the astonishingly beautiful Arianna, he notes that her “perfunctory glance” made him feel like no more than a “handkerchief.” Upon learning his name, she remarks: “What a sad name . . . It sounds like a lost battle.” When he later attempts to consummate their relationship, he feels nothing remotely resembles love or desire:

I put my hands on her small, flat belly, but couldn’t move her. I was frozen and unhappy and there was nothing in me, not even a little of that warmth I would have liked more than anything else in my life, that all-consuming warmth that would have spread from my belly through my body so that in the end I’d be able to reach her. And that low, imploring voice of hers was even worse. Instead of bringing her closer, it made her even more distant, more unattainable, and I was ice cold, inert, filled with sadness.

Such dispassion follows him even through supposed passions, as if he possesses a depth of grief that can never be shared and articulated. He drifts through life in an utter lack of excitement or curiosity, and even for things that marginally tug at his heartstrings, all he feels is a boundless sea of sadness. Time and time again, he confesses—“I was at the end of my tether, truth be told.”

In its refusal to glamorize sorrow or romanticize depression, Calligarich’s narrative of despondence is not just a story that boldly presents the dreary underbelly of life under Fascism, but also a realistic portrayal of tedium as experienced in contemporary day-to-day life. The ripples in Leo’s life aren’t preceded by melodramatic signaling or discrepant foreshadowing; they simply happen without any forced spectacle. When Leo hears the news of his perpetually drunk best friend Graziano Castelvecchio’s death, he responds not with the searing melodrama of a performed tragedy, but only a numb narration of the proceedings. Together, Leo and Graziano had drunkenly evaded Graziano’s wife; Graziano had divulged his story of not being able to perform in the bedroom; they mocked in tandem the existence of God, but in the end, Leo simply handles death with the deadened professionalism of a police officer. Confronted with his best friend’s body, he only remarks that “[t]he cold of the marble was pleasant, and I lit a cigarette, looking at Graziano.” Though having kept up the appearance of being a good friend of Graziano’s throughout the novel, Leo’s relationships are still overarchingly defined by a strong sense of separation—no fond flashbacks of the times spent together, and certainly no uncontrollable displays of emotion at his friend’s departure from life. He finally comes to the realization of his helplessness at Graziano’s funeral, “It struck me as impossible that I couldn’t do anything else for Graziano. But there really was nothing more I could do for him. Nothing at all.”

At the very beginning of Last Summer in the City, Leo proclaims, “I’ve always loved the sea,” and theorizes about how his grandfather’s roots on Mediterranean merchant ships have left an imprint on him. The sea also draws Leo to Rome in the first place. Upon reaching the end of the novel, we discover his real thoughts about the sea: it is a burial place for everything that cannot be born and everything that has died. The sea, a symbol of death to Leo, is the only thing he ever loves or has feelings for—not his reticent father, not the beautiful Arianna, certainly not his best friend Graziano. Jaded in life, he is longing to discover the realm outside his day-to-day consciousness, the invisible sphere of the world that houses all secrets.

The relationship between the often dilapidated city and its residents is a common theme amongst Italian neorealist works. In this vein, our Leo—similar to his relationships with people—feels also nothing for his home city of Milan. Returning after a long wandering in Rome, he only remarks that “the streetcars are great,” while acknowledging that the familiar landscape “still didn’t arouse any emotion in him.” This only changes when he arrives at the street where his home is located, upon which he feels “sick to his stomach” about this place that has undergone zero changes but “ruined everything” for him. It is as if all his wishes to be an onlooker in life and the ultimate, inevitable failures at intimacy are rooted in this single void, one that has been there since he was a child, and one that has crushed any possibilities of emotional truth.

Calligarich’s Last Summer in the City, rendered in tones of rich grey, captures a young man’s stray existence in a city blind to the helplessness of its residents—a continual paradigm of loss and insecurity that pervaded the Italy of the 70s as well as the de-structured and precarious nature of our current times. It is a timeless work of watching life flow past, providing an alternate sea for both the ones who seek to escape the mainstream waters of progress, and those who have been forgotten and left in the wayside.

Ka Man Chung is a writer, translator and the Assistant Director of Outreach at Asymptote. Her translation of Taiwanese writer Chung Wenyin’s Over the Left Bank of the River is forthcoming in 2022.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: