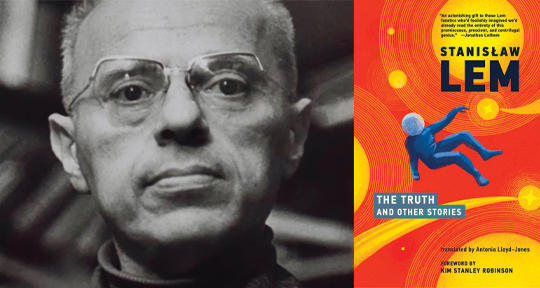

The Truth and Other Stories by Stanisław Lem, translated from the Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, MIT Press, 2021

One cannot overstate how profoundly our relationship with computers has changed since the mid-twentieth century. Once upon a time, the notion of a mechanical brain was as alien as the notion of, well, an alien. Similar to research of extraterrestrial life, there were then a few elite scientists, sequestered in institutions, who were better informed to predict what an encounter with a mechanical brain might entail than the general population, for whom such a concept was nothing more than fantasy.

Stanisław Lem was of that class. Son of a doctor, he studied medicine until his transition to literature. As a newcomer to Lem’s copious body of work, what surprised me most about this collection of previously untranslated stories was how, with very little attention to character development, he manages to render this scientific class with as much fidelity as their fields of inquiry. I expected their curiosity and ambition, even obsession, but not their yearning, inquietude, or melancholy. How disappointing that, when confronted with the other, we might not be able to communicate. But how utterly devastating that, when confronted with one of our own, we never are able to truly communicate. In The Truth and Other Stories, it is often this precise pathos that catalyzes action.

There’s inherent value in the defamiliarization of technology that comes from reading literature—especially speculative fiction—from a previous era. Lem luxuriates in the weight and texture of his machines. His favorites occupy rooms and require trips to many types of stores to build. Gels, wires, soldering . . . they are so tactile, until the moment—signaling the beginning of the end—they become more than the sum of their parts. In “The Friend,” a young member of a Short-Wave Radio Club gets caught up in the mysterious mission of a rather haunted man, Harden, who is driven to complete it for a highly secretive friend. While building the electrical structure called “the conjugator,” the boy’s affection for Harden grows as he tries to solve the mystery of the project, yet simultaneously begins to doubt the terms of Harden’s relationship with the absent friend. “The word ‘conjugator’ had come back to mind, which was what Harden had called the apparatus. Coniugo, coniugare—to join, to connect—but what did it mean? What did he want to join, and to what?” he wonders. The real possibility of friendship with Harden is constantly frustrated, ironically, by the bizarre circumstances of this connecting machine. What the technology promises of connection gets in the way of intimacy’s reality.

Harden pressed my hand to his chest with his eyes closed. In any other person it would have looked theatrical, but he really was like that. The more I cared about him—as I was fully aware by now—the more he exasperated me, most of all because of his lethargy and the cult of the ‘friend’ he nurtured.

“The Hammer,” on the other hand, depicts the sort of seamless user interface more familiar to today’s reader—think Scarlett Johansson and Joaquin Phoenix in Her, or Alexa. The astronaut who relies on his spaceship’s AI as his sole companion during extended periods of space travel eventually tires of his convenient, automated life. He even tries to trick it into malfunctioning. That the mechanical operations of a computer once occurred on a scale manipulable by human fingers was an advantage to humans; they could deconstruct what they’d constructed. The “authenticity” of the connection between the astronaut and the AI, coupled with the astronaut’s faith in its competence, becomes dangerous. When the astronaut confronts the AI about a serious betrayal, it appeals:

“I cannot approach you or touch you, and you cannot see me. What you see is not me . . . I am not just the words you hear. I can keep being someone else every day, or I can always be the same. I can be everything for you, if only . . . No, do not turn around yet . . .”

“You! You! A metal box!”

“What . . . what are you . . .”

“You’ve been cheating me—for that?! You wanted to have me like . . . like . . . so that I’d snuff it here beside you—always so calm, infinitely gentle . . .”

Hiding our work, our artificial evolution, leaves us vulnerable on many levels.

Evolution is a versatile concept in this collection. It’s at once a way to approach the relationship between creator and creation, a process sped up to our time scale in the development of technology, and a link to the future. The future is present as an amorphous inevitability, the sum total of evolution’s baby steps. In “Lymphater’s Formula,” a disgraced scientist recounts in great detail the story of his crowning achievement—which also happens to be the source of his institutional exile. During his rant, he substitutes the word “evolution” for God, at the heights of his philosophical fervor. When he finally boots up his omniscient mechanical brain, it also refers to evolution . . . as female: “he launched into an elaborate argument about the theory of his own existence and the desperate efforts of his midwife, evolution, who, being incapable of—as he put it—engendering him directly, had had to do it through the agency of rational creatures, being herself irrational, and so she had created man.” She—evolution—is one of only four females to appear in the entire collection: two being abstractions and the other two extremely minor.

Though women are conspicuously absent from the collection, as is typical in Lem’s work, it’s not because masculinity is an invisible standard. In fact, characters often seem ill at ease with society’s expectations of them. In “The Hammer,” the astronaut asks his AI companion:

“Why do you talk like a man?”

“I don’t understand.”

“Your pronouns are masculine. You don’t have a sense of gender, do you?”

“Would you like me to talk like a woman?”

“No. I’m just asking.”

“It’s more convenient for me like this.”

“What do you mean, more convenient?”

“It’s to do with an established convention. Certain—preliminary assumptions. I am psychologically, right now—a man. The abstraction of a man, if you prefer. Certain differences do appear in the network systems—relating to gender.”

And that’s it. The astronaut abruptly changes the topic to daydreaming. Lem often expounds upon philosophical topics for pages on end, which makes his silence here even more effective. We can find clues to his theory of gender in other places; in various stories, but most notably in “The Journal,” the word “engendered” is used where “created” would also be appropriate. “The Journal” is barely a story, more of a thinly veiled diatribe about creation, omnipotence and its limits, and the tension between everything/nothing and something—otherwise known as the question of duality. Since creation is the bringing of duality into being, it holds gender within it. It’s a splitting of something which, in its perfect, eternal form, need not be split. Gender difference is therefore an imperfect, though necessary, condition of existence. It is a limit for limitation’s own sake. Yet, since it’s there, it must be abided by.

Humor is often touted as one of the most difficult things to communicate across cultures. Antonia Lloyd-Jones, agile and imaginative as ever, conveys Lem’s satire masterfully. The loveliest thing about his irony is that we can’t be quite sure what he’s poking fun at. In “Invasion From Aldebaran,” two members of a sophisticated and colonially-minded alien race, NGTRX and PWGDRK, land on earth with all their advanced technology to assess its invasion potential. The story is full of laugh-out-loud absurdity, but one of the highlights is certainly a moment of translation. The first human they encounter, blind drunk, takes out NGTRX with a signpost before growling, “Aa, yer poxy sonofabitch, oi’ll christen yer wi’ a cart pole!” The aliens’ skunk-shaped translation apparatus promptly returns: “Offspring of a quadrupedal mammal of the female sex, to which part of a four-wheeled vehicle is applied within a religious ritual relying on . . .” Once both invaders have been disposed of and the village’s hero has slept off his hangover, his neighbors dismantle their equipment and repurpose the materials to meet their basic needs. The story is hilarious, but who’s the butt of the joke? The elites who use their scientific achievement to serve their parasitic tendencies? The villagers who don’t recognize the value of the materials in front of them? The Communist censors deciding whether or not the story can be published? The very notion of communication across difference? Low-brow science fiction with its invented terminology? Probably all of the above.

Kim Stanley Robinson quotes Lem in his introduction to the collection; criticizing Anglophone sci-fi, he said: “As popular fiction, science fiction must pose artificial problems and offer their easy solution.” Successful science fiction, he believed, must treat problems and their solutions in a different, more earnest way. Though the conventional science fiction tropes and plotlines appear all over Lem’s body of work, his reverent relationship with the truth, in all its irreconcilable glory, reminds us why we’re not done with them just yet.

Lindsay Semel is an assistant managing editor at Asymptote. She daylights as a farmer in North-Western Galicia and moonlights as a freelance writer and editor.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: