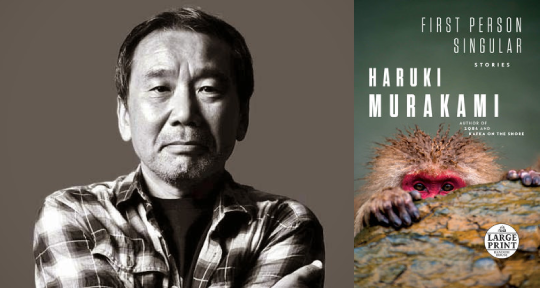

First Person Singular by Haruki Murakami, translated from the Japanese by Philip Gabriel, Knopf, 2021

In Haruki Murakami’s short story, “On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning” (from his 1993 collection The Elephant Vanishes), the archetypal Murakami protagonist—an unreliable, doubtful man—fleetingly encounters an unfamiliar girl on the street and suddenly realizes she is the 100% perfect girl for him, though he has never spoken to her, nor finds her particularly beautiful. Instead, this melancholic, gently absurdist piece concerns itself with what the narrator would have said had he approached the girl. After dismissing a number of ridiculous ideas, the narrator decides on a long fabulist story, in which a young girl and young boy meet, discover they are one hundred percent perfect for each other, and separate to test their feelings. While apart, however, both lose their memories, and when they eventually encounter each other again, both only briefly acknowledge that they are perfect counterparts, but still go on to forever disappear from one another’s lives.

The story, which later served as inspiration for Murakami’s novel 1Q84, employs the author’s recurring narrative device of intermingling reality and unreality in the minds of his narrators, largely applied to the fleeting but transformative romantic encounters between men and women—most famously evident in his early bestselling novel, Norwegian Wood. It also reflects Murakami’s longstanding thematic concerns of loss, estrangement, doomed love, and loneliness. Notably, the young girl and boy not only become estranged from each other, but also from themselves in the loss of their memories; this theme of disconnection unites the stories in the author’s latest release, First Person Singular, fluidly translated from the Japanese by Philip Gabriel. The collection is his first since the English publication of Men Without Women in 2017, and returns to Murakami’s perennial fixations with jazz music, baseball, and mysterious meetings with women and animals. They are all narrated by an aged writer—resembling Murakami himself—who wistfully reflects on loosely chronological formative experiences. In this way, the stories blur not only dream and reality but also author and narrator, playfully employing the lens of memory to grapple with how we transcend—or fail to transcend— the disconnections that occur between others and ourselves.

In classic Murakami fashion, the enigmatic narrators of these eight stories are all referred to only as “I,” except in the most autobiographical of the stories, “The Yakult Swallows Poetry Collection,” in which the narrator acknowledges himself as Haruki Murakami while ruminating on his love affair with the Yakult Swallows baseball team, and the early poems he wrote during the games’ lulls. Like this narrator, the others in this collection also ponder curious incidents that occurred in the recent or distant past. It has become a platitude to refer to Murakami’s plots as dreamlike, but the events described here are inexplicably odd, with illogical turns of events and fantastical details—such as a talking monkey or the appearance of a Charlie Parker album after the musician’s supposed death. Also consistent between these narrators is a psychological distance from these memories, often acquired through the passage of time; they appraise the significance of the incidents within the context of their lives, often by linking it with other thematically related occurrences or in consideration of its lingering moral and philosophical implications.

In the opening story, “Cream,” the narrator recalls an incident at eighteen when a girl—with whom he is barely acquainted—invites him to her piano recital. He arrives to find the concert hall completely deserted, never meets the girl, and instead encounters a man who advises him to discover the cream of life by envisioning “a circle that has many centers but no circumference.” The aged narrator retrospectively considers the significance of this, observing that whenever something disturbing happens, he returns to the idea of the circle, a riddle he has never solved but which remains an abstract comfort, like faith or deep compassion. Murakami places a lot of emphasis on the enduring qualities of memory, manifested in the abstract philosophical idea of “Cream,” texts like the poems in “The Yakult Swallows Poetry Collection,” or a music album in “With the Beatles” and “Charlie Parker Plays Bossa Nova.” In elegiac fashion, Murakami’s reminiscent method of narration meditates on the unlikely ways that memory endures against the inevitable passage of time.

Though the various narrators largely derive a sense of happy nostalgia from the memories recounted in this collection, they also catalogue the losses that arrive with estrangement, primarily of women who have been either lovers or friends. In “With the Beatles,” the narrator recounts his pleasant but ultimately unfulfilling romance with his high school girlfriend; one day, his girlfriend confesses to him that she is the jealous type, sometimes becoming so jealous that it hurts. The narrator admits that at the time, he could not imagine the feeling of burning jealousy, its causes, its consequences. His lack of empathy for his girlfriend suggests not only the emotional distance between them, but also the opacity of her character. The latter is further evoked when the narrator meets the girlfriend’s brother eighteen years after their breakup, and discovers that she has committed a tragic act, utterly unforeseen and incomprehensible. The girlfriend’s brother regrettably admits that “maybe he never really knew her. Never understood a thing about her.”

For Murakami, memory is always an imprecise instrument, throwing into question one’s initial understandings. In these stories, alienation develops when one encounters in others something strange and unknowable, and intensifies even further when the true nature of that encounter is obscured through the lens of memory. As the narrator of “On A Stone Pillow” asks, “Even memory, though, can hardly be relied on. Can anyone say for certain what really happened to us back then?”

Such estrangement, in this collection, occurs not only with others but also with the self, developing when the narrator experiences an incongruity between his mind and reality. This contradiction is playfully evoked in “Charlie Parker Plays Bossa Nova.” Its narrator recounts writing a celebratory article about an imaginary Charlie Parker album—one that couldn’t actually exist because it was allegedly recorded after Parker’s death. Fifteen years after the publication of the article, the narrator visits New York for business, and discovers the actual album he had imagined in a used-record store. Later, he dreams of Parker playing for him. When the physical copy of the imagined album is found, he questions his own perception of reality: “It felt like some small internal part of me had gone numb. I looked around again. Was this really New York?” As in many of Murakami’s works, the self is unstable, prone to becoming reconfigured and refashioned as it floats in a liminal zone between reality and unreality, aliveness and deadness, the existing and the disappeared. This instability is made apparent in the eponymous, final story of the collection, when the narrator resembling Murakami doffs a suit, visits an unfamiliar bar, and starts to feel alienated from the image he sees in a mirror: “The more I stared at my image, the more it seemed less like me and more like someone I’d never seen before. But if this isn’t me in the mirror, I thought, then who is it?”

The instability of both recollection and selfhood is also reflected by the narrator’s uncertainty in the writing process itself. At certain points in the collection, the distance between the author and the narrator narrows when the latter interrupts to question the truth of his own narrative. This postmodernist device is employed in “Confessions of a Shinagawa Monkey” when the narrator starts with a story-within-a-story, describing his encounter at a decrepit mountain inn with a talking monkey, who laments his own loneliness as his affections for human women cannot be reciprocated. The monkey confesses that he used to steal women’s names as a form of romantic love but has since abandoned the habit. Afterwards, the narrator questions the veracity of the monkey’s confession. He hesitates over narrativizing the encounter—it is too bizarre to write in realist style, but also lacks the thematic framework of fiction; this concern suggests his own unreliability as a narrator, and also comments on the fraught relationship between writing memory and truth. For the narrator of “Confessions of a Shinagawa Monkey,” the writing of his memory becomes a way of working out a truth, a sort of “theme,” from a baffling, incomprehensible encounter. He attempts to understand the Shinagawa monkey, his deep loneliness, and his filching of women’s names: “Ever since then, whenever I listen to a Bruckner symphony, I ponder that Shinagawa monkey’s personal life.” Of course—as always with Murakami—the narrator is ultimately thwarted at this understanding, later encountering a woman with a stolen name and left with the uncertainty at whether or not the monkey was being truly honest.

Nevertheless, throughout the collection, Murakami expresses faith in the writing of memory to approach a sort of truth, even if that truth remains ultimately inaccessible. In that sense, the writing of memory is akin to translation, seeking to recreate by interacting with—rather than perfectly reproducing—the original. This belief is most clearly articulated in “On a Stone Pillow,” when the narrator reflects with gratitude on the tanka poems left behind by his former lover, which did not reveal much about the poet, but illuminated the memory of a formative experience: “For the most part [the words] have small voices—they are shy and only have ambiguous ways of expressing themselves. Even so, they are ready to serve as witnesses. As honest, fair witnesses.”

The collection’s encounters with women do suffer from some of the limitations that have appeared elsewhere in Murakami’s work, most notably the problematic representations of its female characters, who can be thinly drawn and sometimes serve—or even sacrificed—as narrative conveniences for the narrator’s self-realization or transformation. This criticism has been leveled against the author by fellow Japanese novelist Mieko Kawakami, who has spoken of Murakami’s tendency to write “female characters who exist solely to fulfill a sexual function,” and for women in his work to be presented “as getaways, or opportunities for transformation.” Nevertheless, the collection does also feature female characters like T* in “Carnaval,” who are much more central figures and whose impenetrable complexity becomes the subject of the story.

Dominant in this mysterious collection are the slipperiness of time and writing as a means of comprehension. In this way, it functions as an autobiography in fragments for the Murakami-like narrator, chronologically weaving from his high school years in “Cream,” to his first publication during college in “Charlie Parker Plays Bossa Nova,” to the death of his father and the deterioration of his mother’s health in “The Yakult Swallows Poetry Collection.” The collection is also a unique contribution to the Murakami canon for its self-consciousness and playfulness with form, through which it scrutinizes the process of writing memory. Just as the self is constantly refashioned, remembering demands a constant refashioning of approach. Murakami’s concerns with the limitations of memory-writing recall those of the narrator from W.G. Sebald’s Rings of Saturn, who also laments the inadequacy of fiction at grasping the truth: “Perhaps that is why we see in the increasing complexity of our mental constructs a means for greater understanding, while intuitively we know that we shall never be able to fathom the imponderables that govern our course through life.”

When the narrator of “Charlie Parker Plays Bossa Nova” hears the music he had imagined fifteen years earlier, he feels as if “it was music that reached to the deep recesses of my soul, all the way down to the very core.” The narrator becomes certain “that kind of music existed in the world—music that made you feel like something in the very structure of your body had been reconfigured, ever so slightly, now that you’d experienced it.” By revisiting this baffling memory, he is able to reconfigure his relationship with music into one that is more deeply felt. In this collection, even as the writing of memory obscures one’s sense of the past, it also clarifies the present.

Darren Huang is a writer of fiction and criticism based in Manhattan. His work has been published in Kenyon Review, Harvard Review, Bookforum, Gathering of the Tribes, and other publications. He is an editor at Full Stop and an editor-at-large for Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: