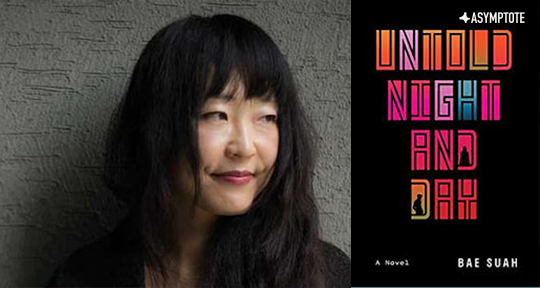

Today, we continue our four-part series on contemporary Korean Literature sponsored by Literature Translation Institute of Korea. Introducing our next title is scholar Jae Won Edward Chung, who last reviewed Yi Sang’s Selected Works (tr. Jack Jung, Joyelle McSweeney, Sawako Nakayasu, and newly annointed National Book Award winner Don Mee Choi).

The Secret Outside Us: A review of Bae Suah’s Untold Night and Day (tr. Deborah Smith)

Ayami, a former actress in her late twenties, works in an audio theater, takes German lessons, and fantasizes about the birth parents she never knew. One day, she has a disturbing encounter with a man loitering outside the theater. When he insists on being let in, their hands briefly meet over the opposite sides of the glass door. Buha is an aspiring middle-aged poet who has never written a poem in his life. He obsesses over a woman poet whose photograph he once saw in a newspaper. He appears to cross paths with her in the same audio theater where Ayami works. Is Ayami the poet? Here, too, their hands overlap without touching. But something is off. The poet woman should be decades older than Ayami. And we know—or think we know—that Ayami is not a poet.

On the surface, Bae Suah’s Untold Night and Day is about alienated city-dwellers stranded in their quest for connection and significance. The novel is filled with creative and intellectual types, most of whom have experienced varying degrees of failure. They discuss theories of photography and obsess about Max Ernst’s objets. Their lifestyle and banter may feel like familiar territory for some readers, but their journey is not without pathos, as we find ourselves in the thrall of the same yearning and fear that grip these artists as their lives unceremoniously pass them by. There are also scenes of levity. In the first section, we’re promised the appearance of a German poet. Seventy pages later, a detective novelist arrives instead, with hopes of taking an inspiring train ride up to Yalu River bordering China (Ayami has to remind him about North Korea).

As the introduction of this detective confirms, Bae is operating within the parameters of the postmodern noir. The balance of the surreal, the cerebral, the melancholic, and the grotesque puts Bae’s work in league with Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 or David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. And as in these works, it pays to be attentive to repetition and variation. Some recurrences are tender gestures, like the touch of a blind girl’s finger on the inside of another person’s wrist, as if taking a pulse. Some seem self-consciously overstuffed with symbolism, like the man in an alley carrying a kitten in a birdcage—a preacher known to slip scraps of Bible verses into other people’s pockets. And let’s not forget the gruesome tale of the cuckolded pharmacist who has a nail hammered into the crown of his head.

Then there’s Yeoni, who teaches German to Ayami and temps as a phone-sex operator. She tells Buha during one of his calls, “We’re looking for a place that has so far remained unknown.” (The word “unknown” here is derived from the same Korean for “untold” in the novel’s title.) She goes on to speak of the “three caves,” a cheeky reference to bodily orifices that also stand for our deepest desires for origin, otherness, and taboo.

Our sleep now flows into the third cave. We go forwards without looking back, our bodies given over to the cave’s energy. We are beside ourselves. We are captivated. Something sucks hard at our flesh and souls. We are no longer ourselves. We are one with the secret outside us, one body.

These lines blending sexual and metaphysical reverie exemplify how, throughout the book, Bae plants clues with which to make sense of the apparent disconnectedness of its characters and events. Another passage describes Ayami’s childhood memory of happening upon a “deep, gaping hole” leading to another world that exists simultaneously with hers. In that world, Ayami is both her future self and past self, existing at the same time. Divisions between fantasy and fact, night and day break down. The wayward details that cannot be resolved away into a coherent, linear temporality loom even more real by the end of the book, as if giving us a harrowing glimpse of ourselves in another life.

Despite the novel’s lithe and disciplined form, readers who prefer more straightforward realism may be frustrated. And even those who consider themselves intimately familiar with Seoul may not recognize their city in Untold Night and Day. On this last point, translator Deborah Smith warns readers against seeking out representative Koreanness in Bae’s works. Being a translator herself, Bae leans toward a conception of literature that might be best described as “non-national.” Hedayat, the Iranian author of Blind Owl, which Ayami uses to study German, was also a translator. There is obvious kinship between Bae and Hedayat. “In life—there are—wounds that—like leprosy—slowly—eat away—at the soul—in solitude.” This first line from Blind Owl appears just twice in Bae’s novel, but its warped echo across language and time casts a long piercing shadow over her work and us.

Jae Won Edward Chung is a writer, translator, and scholar based in New Jersey. He studied philosophy at Swarthmore College and Korean literature at Columbia University. He has contributed to Journal of Asian Studies, Boston Review, Asia Literary Review, and Apogee. He currently works as an assistant professor at Rutgers University. Visit him at jwechung.com.

Read more from the Asymptote blog: