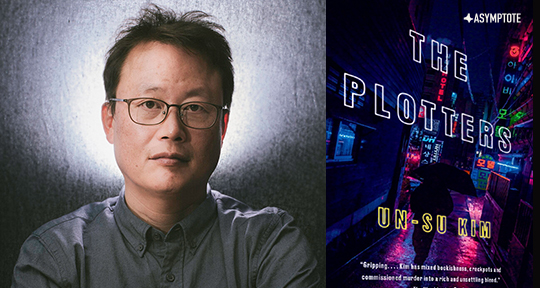

Prize-winning South Korean writer Un-su Kim was first introduced to English readers in 2019 via The Plotters, a hitman thriller that follows protagonist Reseng, a man raised by his mentor, Old Raccoon, to be an assassin. Comparisons have been made to numerous other gangster works, such as films by Quentin Tarantino and the John Wick series, yet Kim’s take on the genre is compelling and unique. After the death of a close fellow assassin, Reseng begins to question his place in this lucrative yet nihilistic industry, as the novel takes a more existential turn. In this review—the first of four in a series spotlighting Korean fiction in partnership with Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea)—Asymptote editor-at-large Darren Huang explores The Plotters as a political critique of Korean capitalism and considers whether it succeeds in subverting the gangster genre.

The soldierly heroes of literary and cinematic works in the gangster genre are often absorbed and then trapped within rigid political and cultural structures defined by their underworlds. In the 2019 Martin Scorsese film, The Irishman, Frank Sheeran, the hitman protagonist, played by a typically reticent and unsmiling Robert De Niro with his curled lower lip, is initially an outsider but assimilates into the Bufalino crime family by adopting the mobster ethos—cold-bloodedness, discreteness, and above all, unswerving loyalty to his superiors. He never seriously questions the instructions of his boss, even when they involve the killing of a longtime friend and mentor. In Mario Puzo’s crime novel, The Godfather, the tragic hero Michael Corleone at first renounces his family business of organized crime and detaches himself by escaping New York to settle in Italy. A number of incidents (including a car bomb explosion that inadvertently kills his wife and an assassination attempt on his father) compel him to return to New York, where he succeeds his father as head of the family organization. He expands his father’s dynastic empire and rises through ruthlessness and cunning to become the most powerful don in the country.

This entangled relationship between the gangster and his underworld is the subject of novelist Un-su Kim’s South Korean 2019 literary thriller and social comedy, The Plotters, adeptly translated into English by Sora Kim-Russell. Like Martin Amis’s London Fields, Kim’s novel centers on the existential journey of a cynical, self-aware epic hero in the form of a gangster. The thirty-two-year-old hitman protagonist Reseng was abandoned as a child in a garbage can on the curb of an orphanage and adopted by Old Raccoon, his foster father and leader of an assassins’ syndicate. Reseng was raised as an assassin in a library, which served as a front for the dealings between Old Raccoon and corporate and government contractors who hired his assassins for the killing of targets. Unlike the protagonist gangsters of The Irishman and The Godfather, Reseng was born into an underworld and destined for a career as an assassin, and, except for a brief stay in the countryside as a hideaway after a botched operation, he has never experienced a life outside of crime. He possesses no family outside of Old Raccoon, whom he considers a father, and a number of older assassins, with whom he trained and formed brotherly relationships. After the tragic death of one of his close assassin friends, he starts to question the senselessness of his life and whether he can escape the underworld. He repeatedly dreams of the ordinary life he tasted during his stay in the countryside, when he worked at a metal factory and happily lived with a factory girl. In the vein of Kafka and Dostoevsky, the novel is principally concerned with Reseng’s existential questioning of the life into which he has been born. Kim reinvents the gangster novel into a political and existential parable by uniquely positioning his protagonist as a questioning pawn within an apocalyptic world.

Like Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Haruki Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, Kim structures Reseng’s underworld in an alternative reality that is close to our own but with a number of distinguishing features in order to critique elements of society. The assassin industry functions as a free market where corporate, government, and even private individuals can hire contractors for the killing of targets as long as they provide sufficient capital. These contractors employ the services of plotters, who meticulously study the movements and lives of their targets to fabricate plots for clean, unsuspicious deaths, and hitmen, who must precisely execute the instructions of the plotters or risk losing their own lives if they fail to realize or deviate from their plots. The assassin industry is characteristic of the underworld in its hyper-capitalism, in its ethos based on the supremacy of capital to the exclusion of all else, including human life. In the underworld, the accumulation of capital and survival for the purpose of accumulating more capital supersede any considerations for morality and human feeling. The alternative world’s hyper-capitalistic structure is most clearly demonstrated by the novel’s meat market, where buyers can buy anything, including human lives and organs, which are the literal “meat” that is sold:

The meat market was the most capitalist of the markets, which meant you could buy anything as long as you had the cash. Nothing there was forbidden by law, justice, or morality. That wouldn’t fit with capitalist principles. You could buy anything here—from a human eyeball, a kidney, a lung, a liver, and other human organs . . . The only things not bought or sold here were cheap emotions that no one cared about (compassion, sympathy, resentment) and powerless, depressing words (faith, love, trust, friendship, truth).

The underworld, represented in this grotesque, exaggerated way, seems nightmarish, a dystopian strain of capitalism. At the same time, it is not implausible as an imagined destination, as a possible future for current forms of late capitalism. That is, the society of the underworld is more an alternative reality than a fantasy. The imagined degeneration of the South Korean system of capitalism into this longstanding hyper-capitalism is also in accordance with Mark Fisher and Frederic Jameson’s idea of capitalist realism, which proposed that capitalism would become the only viable political and economic system and that, eventually, we would not be able to envision an alternative.

In Kim’s novel, the symptoms of late capitalism are all present in hyper-evolved forms. Surveillance and the commodification of personal data have not only become norms but are ubiquitous and streamlined to such a point that any individual’s precise location can be tracked in a matter of days. Data files on an individual’s movements and personal history have become essential bargaining chips between rival contractors. It is also important that the assassin industry is determined by market forces controlled by corporate capital. Kim describes how the assassin industry becomes primarily financed by corporations as opposed to the state: “The boom really took off when corporations followed the state’s lead in outsourcing to plotters. Corporations generated far more work than the state, and the contractors’ primary clientele shifted from public to private.” In South Korean society, the chaebol, family-owned conglomerate corporations, such as Hyundai or Samsung, have long held political ties and been accused of abuses of power related to the running of the government. There have been reports of collusion between chaebol members and governmental officials, so that particular chaebol would receive preferential treatment from the government and contracts for major government projects.

Kim reflects this element of South Korean society when he suggests the hegemonic power of the corporation in his hyper-capitalistic landscape. The connection between the corporation and government is most clearly illustrated when Hanja, Reseng’s nemesis and the head of a conglomerate which contracts services in both assassination and security, seeks to influence the national election with a complex set of plots and killings. The fates of individuals like Reseng are determined by the higher-ups, or the heads of conglomerates, who assess whether his living or dying generates the greater profit. Hanja explicitly articulates the way that individual lives are subject to corporate capital when he warns Reseng, “‘You should care about [number crunching]. Killing you would net me quite a profit. As would killing your mate Jeongan.’” If Kim’s underworld represents a hyper-evolved form of late capitalism, it is one in which corporate capital reigns supreme. Kim also imagines a future in which the state and corporation are inextricably tied through capital, so much so that the failure of a conglomerate to financially back a political candidate results in its dissolution after the candidate and his party secure control of the government. Through Kim’s allegorical structure of an alternative South Korea, the novel becomes a way to think about living in a corporation-dominated late capitalist society.

Kim’s novel joins recent literature and film that offer critiques of South Korean capitalist society and class—most notably Bong Joon Ho’s 2019 blockbuster, Parasite, Bong’s Snowpiercer (2013), and Lee Chang Dong’s 2018 film, Burning. Like the three films, Kim’s novel is representative of Korean mass culture in its reliance on graphic violence and in its dramatization of the struggle between the powerful and the powerless. Parasite focused on the wide gap between the wealthy and the poor by tracing the epic rise and fall of an indigent family of four, which plotted its way into a wealthy household by duping its trusting husband and wife into hiring each of them as either servants or tutors. One of the central conflicts in Kim’s novel is also between the disenfranchised and the powerful in the struggle for power between Reseng, who was born in a garbage can and whose life can be ended at any moment if his murder is deemed sufficiently profitable, and Hanja, whose operation headquarters are located in the uppermost floors of a luxurious skyscraper in Gangnam and who can easily order the murder of Reseng or any of his family and friends and not be held accountable. Kim’s novel offers a critique of the gap between the powerful wealthy and disenfranchised poor in the caste system of the underworld, in which assassins are subservient to plotters, who must answer to contractors, and who are subject to the whims of all-powerful conglomerate heads. The classes of this caste system are differentiated by the extent of their autonomy, with the assassins possessing the least freedom, and their knowledge regarding the killing plots, with the hitmen knowing nothing except the instructions from their plotters. If the hitmen somehow acquire more information about their plots than intended for them by their higher-ups, then they become liabilities and most often exterminated. And if a hitman desired more information about a plot, even the one meant for his own death, he wouldn’t know from whom to seek guidance because the identities of the plotters are never revealed to the assassins. This system, reminiscent of Kafka’s plots in its intricate bureaucratic rules and shadowy oppressors, has been designed to keep the disenfranchised powerless and subservient.

The disparity in wealth and power is also illustrated spatially by the difference between Reseng’s library, which is in decay and freely accessible, and Hanja’s Gangnam tower, which is located in one of the wealthiest districts in Seoul and heavily fortressed. There is symbolic significance to these spaces: the deliberate, understated interiors of Hanja’s skyscraper suggest the corporate class’s inviolability and covert power. In Reseng’s library, unopened books that cannot be sorted are discarded into a fire and “sentenced” to the end of their lives, “the same way aging assassins were added to a list and eliminated by cleaners when their time came.” The discarding of the library books is symbolic of the powerlessness and expendability of the assassin class. A rigid caste system is also central to Bong’s Snowpiercer, where the remnants of humanity, in apocalyptic conditions created by global warming, live in a train segregated by class, with the wealthy elite in well-appointed cars at the front and the poor in derelict rear cars. Bong cleverly arranges the visual elements in his spaces to metaphorically represent class relations. In Parasite, the parasitic relationship between the rich and poor is made explicit in the way the poor occupy the basement of the opulent house owned by the wealthy family they infiltrate. What is common between Kim’s portrayal of the poor and rich and those of Bong is that the classes are firmly demarcated by physical and metaphorical boundaries. Both also pit clever protagonists at the bottom of the social ladder against rigid hierarchical structures designed to perpetuate class inequality.

It is important that in Parasite’s portrayal of class relations, the rich and the poor are differentiated on the basis of character. In the film, Bong sought to subvert conventions in Korean television dramas, Korean gangster films, and Korean cop-prosecutor films, which typically depicted a noble poor or working-class protagonist opposed to the cruel and oppressive wealthy, often with ties to the corporate world. Instead, Bong treated his poor protagonist family with a unique blend of empathy and repulsion, while the rich were represented as kind, innocent, and simpleminded. Bong resisted idealizing the poor or vilifying the rich. The poor are shown as morally questionable, somewhat animalistic, but also capable of human virtue. The protagonist family scuttles on the floors like “parasites,” viciously attacks a rival family, but at the same time, they demonstrate resourcefulness, courage, and selflessness for one another. In The Plotters’ depiction of class warfare, Kim falls into gangster genre type when he characterizes Hanja as a ruthless, self-serving villain. But like Bong, he subverts genre conventions by treating the assassins with a blend of empathy and repulsion. The assassins are also identified as animalistic—the library in which assassins are raised is nicknamed the “doghouse,” one of Reseng’s colleagues is nicknamed “Froggy,” and Reseng often “hides in the dark like a rat.” Reseng can murder an old man who houses him and kindly offers a meal but he risks his life on multiple occasions for the sake of murdered friends and to protect Mito, a plotter who promises him safety from Hanja and who conspires to overhaul the assassination industry. Kim explicitly illustrates the distinction between Reseng’s investment in friendship and Hanja’s cold-bloodedness in their exchange after the corporation head orders a killing of a man close to Old Raccoon. Hanja berates Reseng for improperly disposing the body of an important target, while Reseng shows his remorse for the murder:

“If you’d just turned over the body like you were told, I could have packaged it into something worth selling by now. The politicians and the press can do whatever they want with it after that. I don’t care.”

“He was Old Raccoon’s only friend!” Reseng shouted. “Not that a loser prick like you would understand that.”

In a world which places little value on human virtue, both the powerful and the powerless are morally questionable, but Reseng and the lower classes are the only ones to demonstrate qualities of faith, loyalty, and love.

Kim’s novel is absorbed with Reseng’s existential questioning of this hyper-capitalistic and hierarchical society. His philosophical wrestling with his current life is reflected in his name, which literally means “Next Life” (來生). In The Irishman and The Godfather, Frank Sheeran and Michael Corleone are typical among gangster protagonists in that once connected, they are incorporated into mob worlds, rise through a particular set of exterminating and political skills that extends the hegemony of their crime empires, and become paragon gangsters. Both films exemplify works in the gangster genre through their portrayals of outsiders welcomed into the fold, who become cogs in a machine. They remain committed for life to their crime families and unquestioningly adopt the gangster way of life for the sake of their survival and their organizations. Reseng’s emotional arc, unlike those of Sheeran and Corleone, involves him extricating himself from, rather than assimilating into, the gangster fold. What is unique about Kim’s gangster novel is the protagonist’s degree of self-awareness regarding the criminal life he has chosen. He is conscious of himself as a cog in a machine. His questioning of his role in a factory during a forced retreat from assassin work is suggestive of his thoughts about his place in society: “On his way out, he pictured the factory without him in it. What would change if he were not there? Probably nothing. With or without him, the machines would keep on whirring, day in and day out.” Sheeran and Corleone’s acceptance of their condition as gangsters is replaced in Reseng by existential doubt.

Despite Reseng’s consciousness of the inequalities of the underworld and his increasing sense of the meaninglessness of assassin work, he is haunted by his and his fellow assassins’ powerlessness within his society’s oppressive capitalist structures. Even when he is given the chance to live an ordinary life as a husband and a factory worker, he runs back to the assassin’s life. He is often visited by feelings of resignation to living within an oppressed social class until his life is uncontrollably taken from him by his superiors. In a conversation with Mito, he expresses his lack of agency and acceptance of his existential condition: “I don’t care what you’re thinking or what plot you came up with. I will live my ugly, cowardly, disgusting life, just as you said, until the day someone sticks a knife in me and I’m dead. But I don’t care. Because I’ve lived like a worm and I will die like a worm.” Reseng’s inferior position in an unalterable social hierarchy creates in him bottomless self-contempt and unfulfillment. He feels that whatever he does to extricate himself from his assassin life, “this life is already messed up” and that he cannot “escape this hell.” In Lee Chang Dong’s Burning, the manual laborer Jong-su finds himself powerless to obtain any answers from the wealthy, enigmatic Ben, who Jong-su suspects has killed his friend Hae-mi. In a less subtle but similar fashion, Kim demonstrates the oppression of the lower classes by the elite in a capitalist society, as well as the lower classes’ lack of agency to improve their condition.

In line with capitalist realism, Reseng is doubtful about the possibility of dismantling the capitalist structures that have limited his life to assassin work and a lower social class. He shows his skepticism in revolution when he questions Mito, “‘Will killing Hanja and Old Raccoon change the world?’ . . . ‘It’s just an empty chair spinning in circles. The moment the chair is empty, someone else will rush to sit in it. Killing them won’t make a difference.’” In response, Mito offers a philosophical alternative to Reseng’s resignation when she proposes a plan to remove the heads of the assassin industry and expose the crimes of the underworld. She admonishes Reseng for his doubtfulness and expresses her belief in reform: “‘The world is like this because we’re too meek. Because of people like you who believe in resigning yourselves to apathy, who believe that nothing you do can change anything.’” Though Reseng is not as committed as Mito to a belief in revolution, his questioning of the assassin way of life is in itself a type of resistance. Reseng admits to himself that he once lived “a cowardly life” and that “any life spent not asking yourself what you truly loved was a cowardly one.” But by the end of the novel, he has repeatedly asked himself “What do I want?” He rejects “a cowardly life” by not accepting the life into which he has been born. He disobeys the instructions of his plotters and joins Mito in acting against Hanja. Reseng remains skeptical of Mito’s plans, but his existential questioning leads him into active rebellion against the gangster underworld.

Kim’s novel is not able to envision a future beyond its hyper-capitalistic present. A reformed society lies at a point in time beyond the imagining of the novel. We shouldn’t fault Kim for not supplying this future. This gangster novel transcends the limitations of its genre to create both an incisive political critique and a mirror reflecting the underside of capitalistic society. And one of the defining characteristics of this society is the seeming impossibility of an alternative. Whilst The Plotters doesn’t imagine the revolution of an unjust capitalistic system, at least it offers a powerful vision of resistance.

Darren Huang is a Manhattan-based writer of fiction and criticism. His work has been published in Bookforum, Music and Literature, Gathering of the Tribes, Hong Kong Review of Books, and other publications. He is an editor at Full Stop and editor-at-large for Taiwan at Asymptote.

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: