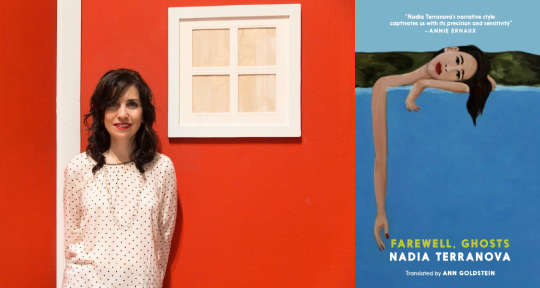

Farewell, Ghosts by Nadia Terranova, translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein, Seven Stories, 2020

Nadia Terranova’s sophomore novel—her first to be published in English—is a carefully crafted meditation on familial ties and the pernicious effects of unprocessed trauma on a woman’s sentimental education. Originally published in 2018, Farewell, Ghosts tells the story of Ida, a thirty-six-year-old woman who lives in Rome and makes a living by writing stories for the radio. One morning in September, she receives a call from her mother, asking her to come home to Messina—a city that Ida has ceased to think of as hers—to help prepare their house for sale. In sorting through the objects of her childhood, Ida will be forced to revisit the trauma that defined her life: the sudden departure of her father when she was thirteen.

Although we are told that Ida’s father, Sebastiano, suffered from severe depression, his disappearance is never explained, nor is it clear if he is still alive. His fate, however, is of little consequence to the novel, which instead lingers with the living—those left behind in the wake of abandonment. Years after the event, Ida’s emotional growth has been stunted by the failure to come to terms with her pain, a failure exacerbated by the lack of a body to mourn, or even the certainty of death. As a result, Ida has grown into a woman who meticulously and egregiously avoids emotion, preferring to reroute her suffering via the “fake true stories” that she writes. She carries herself—and her relationships—with a composure that betrays a tumultuous undercurrent of repressed feelings, acquired through years of conscious disassociation.

There is, for instance, her marriage—described as a “lame creature”—to the dependable-if-too-bland Pietro, perfectly named for his rock-like reliability and immutability. As Ida remarks at some point, “our bodies had stopped functioning together, stopped fitting together in sleep and the waking that precedes it; we had become shields for one another.” Progressively, the novel reveals that this extreme reserve comes from Ida’s adolescent years, in which her mother entrusted her with the care of her father while she went—or, as Ida saw it, escaped—to work. The pain of these years and the culminating abandonment drove a wedge between the two women. “If there was an art in which my mother and I had become expert during my adolescence,” Ida says, “that art was silence.” Even decades later, their relationship is entirely modulated by her father’s absence, governed more by the things left unsaid than those they are able to utter.

It is to Terranova’s great merit that she is able to capture trauma’s potential to stop time in such a limpid manner. Among the novel’s many metaphorical figures (the house and its crumbling foundations, for one) is the alarm clock that belonged to Ida’s father, frozen at 6:16 a.m. on the day he left. “The alarm clock said six-sixteen,” Ida muses, “[and] would say six-sixteen forever.” Victorianists and fans of Dickens will sense a reference to Great Expectations, specifically to the morbidity of Satis House, where all the clocks had been stopped at twenty to nine, the exact time when Miss Havisham realized she’d been abandoned by her lover. Conjuring the specter of Miss Havisham makes abundantly clear just how high the stakes are for Ida, and the extent to which she risks being trapped in the prison of trauma. And while Dickens’s depiction of a woman ravaged by abandonment was inflected by his extraordinary gift for the grotesque, Terranova makes a similar claim about the dangers of remaining stuck in the circuity of grief, even if she foregoes the hyperbolic, opting instead for nuance and realism.

But Great Expectations is not the immediate intertext here. Critics and readers alike will inevitably draw comparisons between Farewell, Ghosts and the work of Elena Ferrante, the pseudonymous Italian writer who achieved stratospheric levels of success after the publication of her Neapolitan Novels. Not only is Ferrante’s latest work, The Lying Life of Adults, being released this month as well, but both works come to us via Ann Goldstein, the superbly talented and prolific translator of much Italian literature these days. However, the reasons for such a comparison should, and hopefully will, extend beyond the fact of a shared translator and the unfortunate paucity of translated literature in the United States; there is a clear thematic and stylistic overlap between Terranova and Ferrante. While the magnitude of Farewell, Ghosts perhaps pales in comparison to the sprawling Neapolitan quartet, the novel does find a close companion in Ferrante’s early work, in particular her first published novel, Troubling Love (both, incidentally, shortlisted for Italy’s prestigious Premio Strega). The two novels center on a woman’s homecoming, both foregrounding the centrality of storytelling in the repression of trauma, and find fertile ground in the otherwise desolate landscape of absence. Both, too, are deeply rooted in their respective geographies—Naples for Ferrante, and Sicily for Terranova.

Terranova’s sense of space, in fact, is masterful. The novel invests much in domestic topography and the urban cityscape. From the symbolic weight conferred on Ida’s house and the repairs that its crumbling roof must undergo, to its keen musings on the intersections between place and identity, Farewell, Ghosts manages to be supremely situated in the Sicily of Greek origins, droughts, and seasonal winds while also speaking to the universal human experience of rootedness and its attending anxieties. “Every atom of me was made of the air of the house in Messina,” Ida says, “and for that reason I would have to leave it.” To Ida, Messina is inextricably entwined to the figure of her father, who, having no grave and being nowhere, is now everywhere. He is in the city itself, but Ida is also convinced that he has “returned to the water,” and that the rain constantly leaking from their faulty roof is another way for him to haunt the family he’s left behind. One must note as well the significance attributed to names: their last name, Laquidara, is a clear play on liquid, and Ida, according to some classical historians, was the daughter of Oceanus.

At thirty-six, past are the formative years of Ida’s life that would make for a traditional coming-of-age story. And yet, in many ways, this is precisely the territory that Farewell, Ghost treads, forming her return into an opportunity to confront past ghosts and close old wounds. A particularly welcome modification that Terranova makes to the lineage of literary works dealing with homecoming and trauma—and something that, I believe, distinguishes her work from Ferrante’s—is the fact that Ida’s emotional growth is measured not solely through her ability to confront her father’s abandonment, but more importantly, through the realization that, in allowing suffering to consume her world, she’s been made unable to empathize with others. If, on the one hand, Ferrante’s work attests to the power of storytelling as a remedy for the worst of ills, Terranova, on the other, displays a markedly more suspicious attitude to this enterprise. “I was the ruler of what I wrote,” Ida says, knowing full well that such autonomy does not translate into her life. In other words, the sovereignty conferred by being the master of one’s fiction is insufficient in the world of Farewell, Ghosts. It’s not solely through the rehearsal and repetition of one’s own story—a quintessentially Freudian scenario—that we can overcome trauma, but instead through a receptiveness to the alterity of others, their stories and pain.

Two relationships in particular drive home the realization that the immensity of her pain has blinded Ida and hindered the possibility of connecting with others. The first is with Nikos, the Greek man partly in charge of repairing the roof of Ida’s home; though she is over a decade older, Ida quickly develops a sense of intimacy with Nikos that will culminate in an eye-opening tragedy. Similarly, she will be led to reckon with episodes of her youth previously believed to be resolved when her old friend Sara meets her with cold reserve. The confluence of these and other events contribute to Ida’s understanding of empathy. They also absolve Farewell, Ghosts from the cardinal sin of many novels of this stock: the solipsism of personal narration. It’s an understandable limitation, perhaps, given the all-consuming quality of grief, but that Ida’s growth hinges not on an inward, but an outward look seems to me notable.

In the end, Farewell, Ghosts is a success. I mean this primarily in two senses. It is, first, a literary success: a tale of homecoming both so familiar and devastatingly new that it is sure to gain Terranova a robust following among English-speaking audiences. In another sense, however, a rarer one, it is a tale of success. Utterly immersed in Terranova’s lush descriptions of Messina and Ida’s fraught relationship to it, I kept returning to something Ferrante once wrote about her native city: “With Naples . . . accounts are never closed, even at a distance.” I was sure Ida’s would be an unresolved story, that she’d never be able to close accounts with Messina. And yet, making her way back to Rome on a ferry as the novel draws to a close, she drops a box with souvenirs from her father into the Strait of Messina, performing her own makeshift funeral for the paternal ghost. Then, she laughs, “and an epoch ends in the sound of a dive, in the sea that opens and swallows up without giving back. I laugh and laugh again, before a tomb that only I know; and at last the small watch on my wrist says six-seventeen.” The circular time of grief is broken.

In times like this, optimism seems like the braver choice.

Photo credit: Daniela Zedda

Victor Xavier Zarour Zarzar is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Comparative Literature at The Graduate Center, CUNY. His research focuses on narrative theory and the works of Elena Ferrante. He has articles forthcoming in journals including Modern Language Notes, Journal of Narrative Theory and Contemporary Women’s Writing. He is managing editor of the journal gender/sexuality/italy.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: