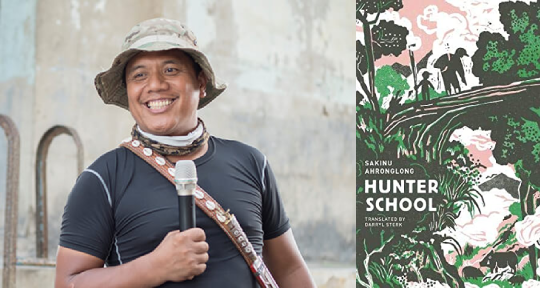

Hunter School by Sakinu Ahronglong, translated from the Chinese by Darryl Sterk, Honford Star, 2020

“I’m dumb,” I told an editor to whom I had shown an essay. “I haven’t read much, and the things I write nobody reads. I can’t write essays like other people.”

“Sakinu, why would you want to be like anyone else?” she said. “Everything in you is literature, things other people don’t have and can’t imitate. Sakinu, let everyone know all the things you keep hidden, let your life story, and Paiwan history, come flowing out of your pen.”

Translation specializes in the improbable, bringing faraway stories to unlikely audiences. The English-language translation of Hunter School (superbly crafted by veteran translator Darryl Sterk) goes further than most in this regard, because although Hunter School was originally written in Chinese, the author has no Chinese heritage, and his people have until recently had no voice in the world of Chinese-language literature, despite being part of the Chinese world; his name is Sakinu Ahronglong, and he is an indigenous man of the Paiwan ethnicity.

Like all of Taiwan’s many indigenous ethnicities, the Paiwan are an Austronesian people more closely related to the Maori of New Zealand than to the Han Chinese who now compose the majority of Taiwan’s population. Though their voices have been marginalized, they remain inheritors of living wisdom, passed from mouth to ear for millennia. Now, Sakinu’s stories have made the quantum leap, first from fireside storytelling to Chinese text, then finally into English, and they are here to show us a new way to relate to our planet and to people who have lived closest to nature for the longest time. This book is a fighter. It had to be. It has fought its way tooth-and-claw through the brambles of oppression—cultural cleansing, intolerant Christians, economic exploitation, etc. etc.—and against all the odds, here it is.

Hunter School begins with the author, Sakinu Ahronglong, in school. Flying squirrel school. Getting to class isn’t a simple commute. Luckily, young Sakinu has a guide in the form of his father, a consummate hunter who holds deep compassion for the animals he meets on his forays, and who teaches Sakinu many things, like the names of the bigwigs in local monkey society. The early chapters are short, leading readers on a tour of Sakinu’s mountain forest childhood and his wilderness education. As the book progresses and Sakinu’s world expands, the chapters stay short. They weave a sequence of life stories, crossing and re-crossing the frontier between a wild ancestral homeland and modern life in a globalized, post-industrial country. In the wilderness, we get to know a world that, for all its wildness, is still very much lived-in (and has been for thousands of years before the Han Chinese arrived in Taiwan in the sixteenth century). These stories show us a new way of imagining the wild realms of mountain and forest, which many of us are only acquainted with (and fond of) from various ventures into the “backcountry.” Of course, it’s only the “backcountry” if you don’t live there. In these pages, we see how people like Sakinu’s grandfather used to live entirely civilized lives in the wild before the time when much of the world’s nature was cordoned off from human society, emptied of most of its indigenous residents, and divided up into national parks, commercial forestries, and mines.

In the translator’s introduction, Sterk writes: “To Sakinu, there is nothing wild about a Paiwan hunter, who is every bit as civilized as you and me, if not more so.”

As young Sakinu ventures wide-eyed out to the big city for the first time, we see glimpses of how indigenous people in Taiwan have suffered. They have been stripped of their humanity and wealth, spat at, and called “savages” to their face. But as Sakinu reflects on his upsetting induction into our modern world so beset with social and ecological ruin, we watch him find his bearings as he develops the idea of a new, more expansive definition of humanity, one that treats all people and all nature humanely, one that knows how to work with the natural world, which is the same way we’d want to treat our family members and neighbours.

“By treating nature humanely, we show our respect for nature and our reverence. Only then is nature generous. It’s not just, ‘you gonna reap just what you sow.’ It’s also, ‘to get, you gotta give.’”

Sakinu’s adolescence was disorienting, a time when the borders between his childhood mountain home and the grown-up world of big cities and manual labour began to blur. He bears witness to friends and family who he saw come unmoored in the currents of modern society and sin:

Ever since I was a boy, I’ve seen my Paiwan tribespeople inundated by society, carried away in the flood . . . Our villages have been invaded by foreign culture, which has fragmented the tribal social structure and deprived us of the totemic tattoos that adorned the bodies of our ancestors. Without the tattoos, many of us try to pass as Han Chinese. Unable to recognize us, our ancestral spirits have not been able to give us their blessings or offer us comfort.

But in adulthood, he finds faith in his cultural inheritance as a Paiwan, and begins to salvage the old ways from neglect and prejudice, to repurpose them for modern, multicultural Taiwan, and to teach them to anyone willing to learn—whether they were Paiwan, Han Chinese, or of other indigenous ethnicities. Today, he has no doubt about his identity as his story spreads beyond Taiwan’s shores:

“I am Paiwan, a child of the sun. The hundred pacer snake is my protector.”

Sakinu also offers a new, indigenous voice in the public debate about environmentalism. Are indigenous people legitimate guardians of wild nature and potential leaders in the environmental movement? Or are they culprits of environmental crimes who don’t know what’s good for them and their homeland? The latter is a common view. Sakinu writes:

People say that hunting is stealing. People accuse us of cutting down trees to build our homes and whittle our handicrafts. People say that by passing on our cultural philosophy we are destroying natural ecology . . .

But as Sakinu introduces us to his family members and shares stories of their connection to nature, he shows us that it’s possible to live alongside nature rather than seal it off in the name of “protecting” it from humans who are not to be trusted to venture within its fragile groves. The answer Sakinu gives is empathy and humility. If we understand nature as human, and if we accept the teaching of our elders and the other creatures who live there, then our intuition will guide the way.

“If you take the bow out every day, then when will the male and female animals have time to fall in love and make love and have children?”

Above all, Hunter School is storytelling, the kind that happens in thirty-minute instalments around a fireplace. The Chinese language sings an altogether different tune in the mouths and hands of indigenous Taiwanese storytellers. Although the younger generations of indigenous Taiwanese speak Mandarin as their first language, and although indigenous authors write in Chinese, the ways they talk, joke, and express themselves are alive with inflections and rhythms independent of mainstream Chinese culture. The Chinese spoken by many Taiwanese indigenous people, or “Mountain Mandarin” as Sterk translates it, is peppered with occasional words from the native languages spoken at home by the older generations, which Sterk preserves in the English translation.

Sakinu and other indigenous writers are reclaiming ownership of their self-expression and creating a new mode of expression that traces a dual lineage from the humanity of wild nature and traditional oral storytelling. There isn’t much distance between the narrative voice and the dialogue, because the narrative is meant to be spoken. It rings true with the steady grace of sound craftsmanship (testament to Sterk’s fine translation work) even as Sakinu summons other-worldly dreamscapes—such as a ghost village of a lost Paiwan tribe buried under dense forest canopy—and leads the reader inside. At times, reading Hunter School felt like crossing paths with a lone traveler in the forest after being a long time alone among the trees, as if he were telling me about the mountain dream realms he’d come through and what lays ahead. Sakinu’s voice evokes a state of deep calm, even though the subject matter is sometimes intense, like standing in a grove of massive Taiwan redwood trees on a still, sunny morning. Even when the stories leave the forest, there is a sense of being anchored to that ancestral place.

One of the inspiring things about this translation is its potential to reach not just an undifferentiated mass of global readers, but to build new bridges between Sakinu’s real-life Hunter School—a back-to-nature movement—and other indigenous communities and leaders across the world. He was surprised to learn during a visit to the USA that several Native American tribes he visited didn’t know there were any indigenous people in Taiwan. Despite the challenges, there has already been some international exchange, including a delegation of New Zealand Maori writers visiting the Taipei Book Fair.

Taiwan’s government is one of the most progressive in the world when it comes to recognizing and working with indigenous people. It’s still far from perfect, but the government is at least giving indigenous groups some space for self-determination. Some of the native people of Taiwan, Sakinu Ahronglong foremost among them, are now returning to their ancestral lands as guardians and educators. They are building movements, building partnerships for the future, and formulating new ideas that have a lot to offer to twenty-first century urban dwellers looking for a new way to relate to our planet. This beautiful book is part of a historic new chapter in world literature.

Saul Thompson is a freelance translator from Chinese and French into English. Saul has translated and published six books of different literary genres from Chinese into English. Saul received his training in Chinese at the University of Cambridge’s Chinese faculty. He is particularly interested in texts relating to the natural world and indigenous cultures.

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: