On the tails of its celebrated success in Russia, Narine Abgaryan’s award-winning novel, Three Apples Fell From the Sky, is now available to English-language readers in Lisa C. Hayden’s expert translation. This tripartite tale takes on the form and mysticism of fable to spin a narrative of a village constantly at the mercy of catastrophe, and, as Josefina Massot points out in this following review, may act as a poignant response to our current age of precarity. With its characteristically sensitive descriptions, Abgaryan’s work explores the human things that evolve in the aftermath of disaster; in times that teeter on the edge of dystopia, it invites us to read our lives into them—a reminder that one of literature’s most enduring gifts is its expansiveness.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

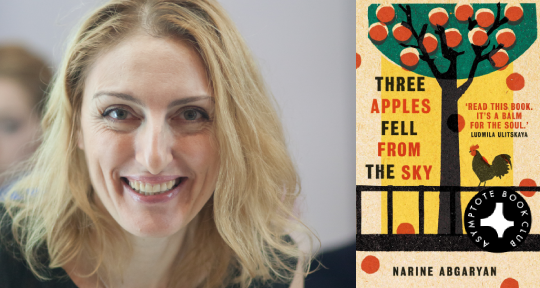

Three Apples From the Sky by Narine Abgaryan, translated from the Russian by Lisa C. Hayden, Oneworld Publications, 2020

They say the best way to ward off anxiety is to focus on the here and now. At the moment, though, “here” is a seemingly shrinking apartment and “now” is any time I hit refresh on decidedly growing pandemic statistics. It’s been that way for weeks, so when Abgaryan’s novel hit my inbox (my locked down city’s impermeable to foreign paperbacks), I was desperate for a folktale. What better than a nowhere, no-when land to flee the grim here-and-now—a tale that would end happily, or at the very least end, flouting the boundless infection curves that plagued my feeds and fed my dread?

Three Apples Fell From the Sky isn’t the strictly uchronic utopia I’d expected: most of it unfolds in the Armenian village of Maran during the twentieth century. When I googled “Maran Armenia,” however, I found no such place, and the search I then ran on “Մառան Հայաստան,” courtesy of Google Translate, yielded a stub on a village for which “no population data had been retained.” In fact, there seems to be no data at all—just an unverified note on villagers’ deaths and deportations during the Genocide. As far as I was concerned, Maran might as well have been fictional. Grounding the novel in time proved equally tricky: save for a few scattered references to telegrams or left-wing revolutions, its protagonists could’ve just as easily lived through the 2015 constitutional referendum or the Russo-Persian Wars. My sense of chronology was further challenged by recurring flashbacks, occasional changes in verb tense, and the Maranians’ own cluelessness regarding dates. Near perfect fodder for escapism, you’d think, but by the time I’d put it down, I was more firmly rooted in the times than ever.

It took me a while to realize why Abgaryan’s folktale was so improbably of the moment. Part I opens with fifty-eight-year-old Anatolia as she “lies down to breathe her last”: she’s convinced that the blood flowing copiously from her uterus can only signal death. As she awaits it, she recalls a haunted childhood and violent marriage, along with the solace she’s found in books and friendship. Meanwhile, unaware of her ailment, neighboring Yasaman and Ovanes plot to hitch her up with widowed Vasily, a kind-hearted blacksmith whose background is gradually revealed. Undeterred by an initially reluctant Anatolia, Vasily prevails and their union leads to a series of unearthly events in part III. Interspersed throughout are other villagers’ stories—including old couple Vanos and Valinka’s dealings with a seemingly enchanted peacock in part II. All utterly delightful stuff, to be sure, but not exactly timely at first glimpse . . .

Then it struck me. If the current pandemic mindset can be more or less gauged from my own, my friends’, and vocal online strangers’ alike, then it’s fair to say that most of us are dealing with at least three major issues: we fear looming death, and—forced into quarantine—we struggle to connect with others and to quit the hallmarks of a “life lived big” (these hallmarks are widely subjective, but they do tend to include the great outdoors to some degree). On all three fronts, as it turns out, there’s much to learn from the Maranians.

Their lives are steeped in death: half the village falls to the abyss after an epic earthquake, the able-bodied die at war, the feeble die from famine, a girl and her bloodline are cursed by her dead sister, a remarried widower keeps spotting his dead wife, and a boy who sees death angels comes to foresee (and forestall) death itself. Maranians mourn death’s toll, but likely due to its unyielding presence, they seem to have made peace with it. To quote their favorite line: “that’s probably how things are supposed to be, because that’s just the way it is.” It may sound defeatist in the current context, but I view it as a call for equanimity amid generalized panic—something like the mantra that urges us to let things be exactly as they are, even as we work to change them. It’s not about capitulation but acceptance.

Maranians also prove that solitude need not thwart solidarity. Their village, perched atop treacherous Mount Manish-kar, is virtually quarantined from nearby towns, and they’re routinely pushed into isolation by all manner of external foes—from bitter winters to a bug invasion that eerily mirrors our present. Even on the best of days, an “essence of crushing solitude seems to flow out of each house.” And yet, they’ll join forces when they need to, be it building a stone barrier in record time to protect the village from a mudslide, or cleaning up after a neighbor throws yeast into her cesspit and it rises overnight to flood half her backyard. Anatolia marvels at “the unseen threads that connect them with each other” in spite of it all; now that these threads seem more tenuous than usual, we’d do well to remember them too.

Finally, Maranians teach us that a life can be well lived without being fast and furious. Beleaguered by tragedy, they spend their days indulging in small pleasures—tending to their animals, their gardens, and their laundry. Once again, Anatolia gives voice to a collective sentiment: “There was so much that was offhand and ordinary in the clinking of spoons, the request to pass the salt and slice a piece of cheese, or in a swallow of water and the slightly dry heel of the homemade bread, that [she] sensed for the first time that life was a gift, not something to take for granted.” The novel’s tone meets content here: given the array of epic horrors she alludes to, Abgaryan could’ve opted for fast-paced, action-packed narration; instead, she goes for delicate portraiture. Maranians’ rituals are described minutely and—to use one of the author’s pet terms—sedately. One of the finest examples in this sense is also the first:

[Anatolia] thoroughly watered the kitchen garden and scattered food for the chickens, leaving a little extra since the birds couldn’t go around unfed (. . .). After that she took the lids off the rain barrels that stood under the gutters (. . .) in the event of a sudden thunderstorm, so that streams of water pouring down wouldn’t erode the foundation of the house. Then she rummaged around the kitchen shelves awhile, gathering up all the uneaten supplies—flat little bowls with butter, cheese, and honey; a hunk of bread; and half a boiled chicken—which she brought down to the cool cellar. She also pulled her “grave clothes” out of the wardrobe: a woolen dress with a high neckline, long sleeves, and a small white lace collar; a long pinafore with satin-stitched pockets; flat-soled shoes; thick knitted socks (she had suffered from ice-cold feet her entire life) (. . .), meticulously laundered and ironed underclothes, [and] her great-grandmother’s rosary with the little silver cross.

This kind of leisurely, painstaking prose—in Hayden’s lyrical translation—is an added gift for readers at the moment, because it prompts us to adjust to the “measured pace of existence” that is now also our own.

Three Apples Fell From the Sky borrows its title from a classic Armenian saying, which (with slight variations) opens, closes, and divides the novel into parts: “one apple for the one who saw, another for the one who told the story, and a third for the one who listened.” At least two apples have fallen into worthy hands: Maranians see plenty, and Abgaryan knows just how to convey their lessons. It’s now up to us readers to heed them, but one thing’s certain: they’ve never been riper for the picking.

Josefina Massot was born and lives in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She studied Philosophy at Stanford University and worked for Cabinet Magazine and Lapham’s Quarterly in New York City, where she later served as a foreign correspondent for Argentine newspapers La Nueva and Perfil. She is currently a freelance writer, editor, and translator, as well as an assistant managing editor for Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: