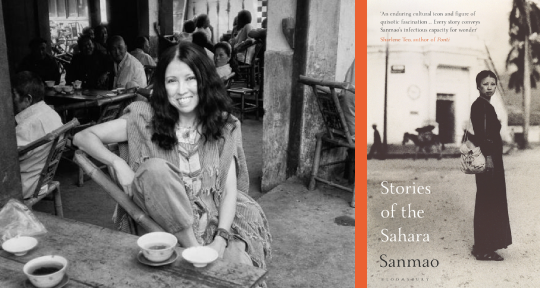

Stories of the Sahara by Sanmao, translated from the Chinese by Mike Fu, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020

Around ten the night is wine-inspired, and even the most tight-lipped Chinese émigrés, bruised from decades of survival, come around to reminiscing. Shenzhen and Xiamen and northeastern accents collide, comparing childhood hardships, fears, regrets. Sunflower shells are cracked and peanut skins snow the table, and the dialogue coheres at a single incredulous certainty: how lucky. How lucky we are to be here, because how easily it could have been otherwise.

One of the most beloved characters of most Chinese children born after 1940 is the infamous Sanmao (三毛 / Three Hairs), a pitiful orphan so impoverished he could only manage to grow, well, three hairs. Set largely in nationalist Shanghai, the narrative of Sanmao detailed his nomadic wanderings, involving most often ignominious miscarriages of justice, teetering hunger, and desperate, one-yuan schemes. Round-headed, ribcage-baring, picking up cigarette butts on the street, Sanmao was adored by children like myself—poor but not destitute, bred with an uncertain yet determined idea of the world’s cruelties, cultivating a helpless, weary sort of empathy for a two-dimensional friend.

It’s strange that we live in the age of Crazy Rich Asians, because our formative stories are still about paucity; in a history defaulting on need, not enough time has passed to allow for much of anything else. Wealth, burdened by its relativity, meant that compassion for the less fortunate simultaneously possessed the more utilitarian purpose of stoking flames of aspiration. The age inoculated with the pathos of Sanmao is characterized by a fierce survival instinct, one that breeds a sharp protectiveness and a craving for stability. There is no doubt in my mind that my mother handed me a copy of The Wanderings of Sanmao in hopes that she was in the process of raising the next foremost cardiac surgeon, saved from a life adrift. It is an incredible anomaly, then, that one of the greatest literary wanderers in the Chinese language chose to take on Sanmao’s name for her own, overpowering his numinous survival with her own, insatiable desire for the extraordinary.

Sanmao, the nomadic Taiwanese writer, storms her way into the English language with the travelogue that defined her restlessness and raw talent for narrative: Stories of the Sahara, now appearing via the dedicated and sensitive translation of Mike Fu. In 1976, when Stories was first published, Chiang Kai-shek had just died the previous year. The Kuomintang, steadfast in its late leader’s convictions, vowed to never compromise with the Communist mainland. There were children and adults who had never lived in a country free of martial law. This book—unleashed and contrary, occasionally jubilant and startlingly present—was to a starved populace an elixir. The world, bound and weakened, was all of a sudden astoundingly everywhere.

1973: Sanmao answers a call from the Sahara that had been quickening for years. Her lover José, prescient of her will, had taken a mining job in the Spanish-occupied region of the desert and prepared for her arrival. She arrives in El Aaiún, and the days begin, days that would become years, drastic and panoramic years in both geographical and emotional survey. The Sahara is uncontainable, and so is she. The stories, told with the quick-hand of someone torn between the eagerness of telling and the compulsion for leaving, make up a psycho-topography of interior travel. Arguing with neighbours, peddling fish on the streets, escaping the hands of vicious men, taking a driving test, suffering a cursed stone, witnessing the inseparable duality of love and cruelty—the woman and the desert devour one another.

Of her nearly twenty books, Stories of the Sahara is perhaps the least contemplative, and most exuberant. Writers keep journals because of an immutable intention to reform the world into a place of their own—between the margins of a text, retelling completes the phenomenal trajectory of being into knowing. The process of writing—its linearity—defies the disorientation of the body, strained by memory but anchored in time. We do not read journals simply because we are curious about the stories told within them; it is the intensification of experience that fascinates. Stories of the Sahara is a relic of imperfect passions, of individual design that shamelessly centralizes the self; the infinity of her environment is imprinted by way of her architecture. Her I maintains such vivacity by never adjusting herself to standard; she is so often reckless, petulant, naive, and emboldened by the idea that there are no consequences to her actions, perhaps because she has no obligations to the land. Closing the book, we are not left with the knowledge of what it was like to be there; we do so, knowing that she was there.

The woman’s journey is often an anxiety of identity, a warring of body politics and self-consciousness of representation. Sanmao is aware of her bodily strangeness, but does not allow her recognized identity to take presence over her physicality. Rarely does she interrogate her alien status—peripateticism having long overwhelmed such didactics. She neither accuses her femininity or ethnicity, nor attempts to defuse it by way of social negotiation—these qualities are, to her, as transferrable and amenable as elastic-waist clothing. The sharp impressions of her locality give the sense of her life as experiment, thrill of discovery and novelty overwhelming self-categorization. Identity does not take precedence over physicality, and the ecstatic shattering of past lives leads to the manifestation of a different otherness, one that is not threatening, but simply separate. In watching, she never wonders what it is like to be watched in return. She refers to her desert home as a Chinese restaurant, exclaims to José that he is “Double-Oh-Seven and I’m the evil Oriental woman in the movie,” and thinks little else of it. It is, perhaps, a definition of freedom.

Outside perspectives can never shatter their own narratives, however, and the writer does not hesitate to pass judgment on her surroundings. In witnessing a Sahrawi bath by the sea, which apparently involves a rather extensive, seven-day-long series of enemas, the writing slips into gleeful exposé—“We were scared shitless, watching from behind the rocks.” The entrenched methodology of discovering the world by conquering it has had an immutable effect on humanity’s conceptualization of space—because we cannot be physically present without taking possession, our capacity for envisaging mutual terrains is incapacitated. As flippant and obtrusive as Sanmao sometimes is, her redemption is in her unwillingness to subdue; confronted with the breathlessness of desert wind and its enwrapped people, she allows herself to be gloriously, mesmerizingly captured:

There is no other place in the world like the Sahara. This land demonstrates its majesty and tenderness only to those who love it. And that love is quietly reciprocated in the eternity of its land and sky, a serene promise and assurance, a wish for your future generations to be born in its embrace.

In his poem, “Companions in the Garden,” René Char writes: “Let us not permit anyone to take away the part of nature we hold in ourselves. Let us not lose a stamen of it, let us not surrender a sand-grain of it.” Yet arbitrarily, the bulk of us set out in this world banishing our wildness, displacing it with the grace of functionality, of having a rightful place, of peace. We are engrained with a binary opposition between humanity and wildness, so what has led to this desire for wandering—the desire for deconstruction? Isn’t there something inhuman, something distinctly pitiful, about someone who refuses to—let’s just say it—settle down? Ancient Chinese nomads set off on their journeys in search of something—harmony, transcendence—but she describes her infatuation not as pursuit, but as homecoming. “A lifetime’s homesickness, and now I’ve returned to this land.”

There are, however, moments when even she is doubtful of her tendencies, especially when the desert reclaims her human comforts:

… there is no such thing as excessive joy, yet nor is there much sorrow. This unchanging life is like the warp and weft of a loom, days and years being woven out line by line in an ever-monotonous pattern.

But they are brief and, it seems to her, too uninteresting to pursue—there is something else, wonderful in the distance. Sanmao was born in Chongqing, grew in Taiwan, and became in a myriad of places: Spain, Central America, Germany, the unfathomable Sahara. It seems to me that she adopted the name of a nomad to conquer the absolute that one is forced into migration. Sanmao, the orphaned boy, was the defeated product of a painfully fragmented world. Sanmao, the everywhere woman, is a revelation that pieces of a multi-located self is a multiplicity of existences. That a place-bound spirit defies what we owe to ourselves. That the part of nature we contain, should we allow it, will conjure us back to its boundless motion. Coming home.

A passage in the Daoist classic Zhuangzi 莊子 speaks of restlessness: a bird, whose wingspan stretches to seemingly unending distances, looks down at the sky, which is so infinitely blue, and wonders if finality even exists. Wildness is the rejection of limits, which is, of course, the rejection of endings.

Diaries do not take particularly well to translation, as their languages, more faithful to mobility than to the stationary, are living. In Mike Fu’s rendition, however, the reluctance of the original language to relinquish its ownership is mediated by the mostly elegant simplicity of an English that does not try to capture the impossible quality of Sanmao’s voice, but commits to the more archaeological qualities of text. Sifting through the sentences, a form emerges, and though she is as unreliable to us as we suspect she is to herself, patterns of life are also unveiled. Inevitably, however, some of the humour of the original—contributed by the frequent hyperbolic and rhythmic, adjectival phrases of Chinese—dissipates, creating a mirage, dramatics and laughter dangling.

Sanmao, of course, does her share of translating. Her reiterations of conversations are all in Chinese, which has the funny effect of making everyone talk as she does. In this one finds her way of loving: a woman goes to the desert because she is convinced that the desert is her soulmate from a previous life, she marries a man there, her partner in this life, and she takes both lovers into herself, along with all the other people who happen to pass by. This consummation is not possession, but extension. She lends her idiolect like a gift to everyone she encounters. The English language follows her lead—it does not own her, but expands her.

The legacy of Sanmao in Chinese-language literature is one that is dependent on her place in its timeline—it is a cabinet of curiosities, awakening dreams, exponential interiority. It did not seek to define or argue or defeat in a time when the text had been perfected as weapon, when the Chinese language was shredded from decades of manipulation and coercion. There is nothing in it resembling deception, not even beauty. Her writing is not beautiful—it seems dismissive of poetry even as she quotes from the Chinese classics, preferring to engage with the affair of the senses in tactic and haptic lines, a rollicking past tense eliciting the image of someone having rushed home to tell you something wonderful they had just seen. When she finishes her exhilarated account, she falls back. You have to see it for yourself, she seems to say.

So what does she offer the English-language reader, whose repositories are well-stocked with stories of travel and adventure and awakenings? The screenwriter Shi Hang 史航 said something quite wonderful: “Sanmao is a girl with cold hands; when she touches warmth, she feels it with more intensity than the average person.” Others have been more brusque: “Strange person, strange behaviours, true love, true words.”

The most powerful story of the volume appears near the end, under the title “Crying Camels,” detailing the brutal consequences of the conflict between Spain and Morocco for control of the Western Sahara. It is also one omitted in certain Chinese-language editions. In a rare literary flourish, the story is told in traumatic flashback, culminating in a horrifying public rape and murder. In the Chinese version, Sanmao’s lines, which normally begin a new paragraph after nearly every sentence, suddenly crowd the eye in a jarringly aberrant block of text when describing her recollection of this depravity, almost as if she is trying to get the words out as quickly as possible, as if she cannot bear them. The sentences stutter. Though her I is still there, it is no longer commenting and curating, but desperate. Frantic.

The crowd started screaming and fleeing the scene. I desperately tried to get closer, but I got pushed and staggered backwards. I opened my eyes wide, looking at Luat surrounded on all sides. He was pulling Shahida along the ground, his eyes wild and alert, a ferocious glint in them.

There are few writers, in the Chinese language or otherwise, who are exacting this aliveness on the page, who tells a story as if she is trapped within it. Who writes a memory as if convinced that it is the only way to know its reality. She tells her sister—one imagines, dismissively—“One lifetime of mine is worth ten of yours.”

She committed suicide in 1991 at a hospital in Taiwan, over ten years after her José’s death and the end of her nomadism. Three days later, the China Times prints a piece of hers, characteristically plainspoken. For the women who had grown alongside her, envied her, fallen into foolish, adulating love with her, booked one-way tickets to the Sahara in search of her mysticism—it was the familiar voice of a friend who has returned from a long journey, sitting close on a makeshift wooden chair, one leg up on the seat, hair downed with sand-waves.

假如还有来生,我愿意再做一次女人,做一个完全不同的人,我要养一大群小孩,和他们做朋友,好好爱他们。

我的这一生,丰富、鲜明、坎坷,也幸福,我很满意。

过去,我愿意同样的生命再次重演。

现在,我不要了。我有信心,来生的另种生命也不会差到哪里去。

If there’s an afterlife, I would like to be a woman again, a completely different woman. I want to raise a big flock of kids, to be their friend, to love them well.

This life of mine—rich, clear, rough—has been blessed. I’m full of joy.

In the past, I would have wished to repeat the same life.

Now, I no longer do. I have faith, that in the afterlife, another one wouldn’t be so bad.

In Chinese, the most common word for dying is “去世,” to leave this world. In Taiwan, they use the Buddhist term, “往生,” towards another life. It is both odd and incredibly painful, and almost miraculous that Sanmao, even in death, urges towards the various. How easily it could have been otherwise—one says in fear, and one says in wonder.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet born in China and living in Tokyo, Japan. Her chapbook, How Often I Have Chosen Love, was the winner of the Frontier Poetry Chapbook Prize. She currently works with Spittoon Literary Magazine, Tokyo Poetry Journal, and Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: