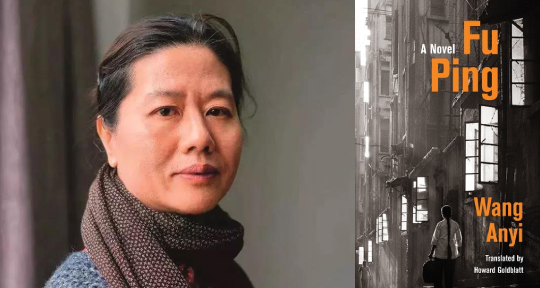

Fu Ping by Wang Anyi, translated from the Chinese by Howard Goldblatt, Columbia University Press, 2019

First, do not create extraordinary circumstances or extraordinary characters. Second, do not use too much material. Three, do not over-stylize the language. Four, do not aspire to be singular.

These strange and somewhat alienating pillars of writing philosophy are passed on to us by Wang Anyi, one of China’s most accomplished and notorious authors. Famed for her meticulous portrayals of female tenacity, ordinary citizens, and everyday minutia, she is both stylistically audacious and devoted to her subjects. Fu Ping, her most recent novel to be translated into English, and taken into a wonderfully equal rendition by Howard Goldblatt, exemplifies the thematic and aesthetic constants prevalent in her oeuvre, while simultaneously creating an illumination of city and community that leaves remarkably deep impressions by way of its quietude.

Fu Ping has arrived in Shanghai as a designated bride for Nainai’s grandson, Li Tianhua. This is our simple premise. She, as the title character and the Trojan horse by which the reader is implanted into the direct centre of the novel, is as impeachable and indecipherable, upon first glance, as the wooden horse itself. The bulk of the chapters and passages are dedicated to the lives—lived simply and somehow immensely at the same time—of the characters that inhabit her newfound society. This collage style, free of distinct plot or obvious crescendos, is characteristic of Wang’s tendency towards pluralism. Though Fu Ping is the first character introduced to us (indeed, her name opens the book), a single scant paragraph is dedicated to her arrival, before the narrative turns to traversing the history of the woman she has come to meet—Nainai (Chinese for grandmother).

All in all, though she’d lived in Shanghai for thirty years, Nainai had not been transformed into a true urbanite, and yet she was no longer a rustic; she was, instead, a hybrid—half urban, half rural.

The chapter goes on to detail Nainai’s colourful and various existence throughout her time in Shanghai, and does not return to Fu Ping until much later. Composed in third-person omniscient, the novel occasionally digresses into the mind and thought of a single individual, but rarely lingers there for long. As a result, the structure, delineated and travelling through person to person, their stories, their histories, is ambivalent—or even unaware—of chronology. If it were not for the single connective tissue of Fu Ping’s arrival within this small, working-class Shanghai community, it could be taken as a book of short stories (a genre Wang has thoroughly explored in multiple publications).

There’s a saying in China: 柴米油盐. Directly translated, it means: “firewood, rice, oil, salt”. In intent, it means: we need very little, bare necessities are enough. This spareness, born in part out of scarcity, is embodied in Wang’s careful, exacting prose. Goldblatt does a remarkable job in the transference of this stoic voice into English, using transliteration where appropriate, and inserting lyrical pauses naturally in the language to mimic the freer use in Chinese of commas. As the novel is completely free of dialogue (conversations are written in the form of reportage), the maintenance of such a modest and—as Wang herself dictates—understated voice may earn the novel some criticism of being somewhat monotonous, but Goldblatt is entirely devoted to Wang’s original, and it culminates in an admitted slowness, the same way that a painting is slow—so it is that the reader is led to the details within the prose like a viewer is eventually led to all the contours and shadings of a portrait, coloured stroke by stroke until the entire world emerges.

Simple though it may be, the narrative unfolds in a way that resembles the oral tradition, by which ancestral stories are inherited. It is important to note that in China, the lives of one’s family (which often include not only blood relatives, but also those whose lives are lived proximally to one’s own) are not separable from the individual self, but intricately interwoven; the collective narrative is relayed with as much familiarity as the individual one. In the use of this voice, descriptions are always tinged with the shadow of remembering. The path through this literature is the dedicated—almost secretive—manner by which tales are passed from ear to ear, and finally released to us by way of someone we trust.

It is also impossible to talk about Wang Anyi and her work without discussing the politics of feminism in China. Though propagated in theory during Mao’s reign, largely for reasons of infrastructural development, in practice gender equality is weighed against more enduring notions of female “roles,” an insistence on feminine beauty and traditional traits, and of course, the historic bias against daughters that has led to uncountable cases of infanticide and abandonment. In a way, a lot of courage is required for a woman to write unsympathetic female characters in the context of such politics, and Fu Ping is not only unsympathetic, she is slow to be developed, and reticent to the point of almost disappearing. As we delve into her evolution throughout the course of the novel, however, Fu Ping’s character—tenacious, resistant, mute but fiery—evolves in a slow tide as an undercurrent amongst the descriptions of equally indefatigable female characters around her. Take the following passage:

Fu Ping stopped eating, so annoying Xiao Jun that she crammed a flatbread into Fu Ping’s hand and walked on, still chewing. Fu Ping followed her until the crowd thinned out, when she lowered her head and took a bite.

There is a clear distinction of activity and passivity here, and it demonstrates the role that Fu Ping occupies. By placing her titular character largely in the background, Wang disrupts the common notion that the only way to rebel is to do so with undeterred brashness. In most cases of self-assertion, certain elements must align: education, community, resources. Full awareness of one’s own abilities is often a further precondition. Fu Ping, a young, orphaned girl newly implanted in Shanghai from Yangzhou, possesses none of the aforementioned. Indeed, her mental and characteristic isolation is exactly derived from her physical isolation, and Shanghai’s resistance to her integration. Her quietness, then, is her fortitude. Her reluctance to act or her instinct for simple escape is a consequence of her own form of boldness. Endurance—or as the Chinese say, the ability to “eat bitterness”—is a long-established ideal of courage in China, which is to say, sometimes the bravest thing is not to vigorously seek change, but to hold on to yourself, and your life, during the times of immense difficulty. As the novel progresses, the choices Fu Ping makes, even the seemingly unremarkable ones, slowly puncture the outer shell of the girl to reveal the desires and pertinacity of a woman who arrives, through enormous tides, at herself.

Wang Anyi, despite being a homegrown and long-term resident of Shanghai, is intensely curious about the individual natures of the migrants and drifters who flow in and out of Chinese metropolises, drawn in by the promise of wealth, opportunity, and equally sparkling potentials of a newer, bigger life. As is standard with writing at the place where the countryside meets the city, there is the fixation on simplicities even amidst the endless chaos of urbanity; between the dense lawlessness of Shanghai’s perpendicular alleys, coarse smoked brick, and irregular structures, we are still admitted into passages that conduct in respites of peace:

Moss grew on courtyard walls and on a pair of buckets. Potted plants lined up on the concrete terrace included a China rose in full bloom. Bedding was drying under the brilliant sun on balconies, clothes were drying on bamboo poles crisscrossing the area overhead. It was early afternoon. They were alone in the sun-drenched courtyard, while street noises were muted, as if filtered through a membrane.

There is, however, no unnecessary enchantment in the language which adopts the Shanghai vista; descriptions have the familiar feeling of having been seen thousands of times, quotidian enough to have been drained of intense emotion. In the patchwork format by which this novel takes its shape, the reader is as involved and intimate with the surroundings as one of the characters. Unlike those who succumb to the pitfall of romanticizing rural “simplicity” by degrading urban excesses, Wang is more reluctant to weave overt beauty or sentiment into her narrative. The prose lies on the fringes of poverty, always recalling the crowded overwhelm of deprivation:

Every smell imaginable fills the place: the musty aroma of pickled vegetables, the foul door of a baby’s urine, the sulfuric smell of burning coal, stale-food odors, a heated mixture of aromas amid which the teacher lives and reads, his head bobbing from side to side, holding a little stoneware teapot in which broken bits of tea leaves steep.

As the times change, so does time itself. It is 1965—the eve of the Cultural Revolution, a fact never acknowledged in Fu Ping. What is painstakingly clear, however, is the instinct for survival amongst the citizens, humanizing the people who are swept up in the recurrent tumult of the Chinese nation. Wang said in a 2008 interview that her fellow Shanghai residents hope that she will write in tune with Shanghai’s vibrant modernity; they are reluctant to delve into the Shanghai of the 50s and 60s, out of fear of seeming dated. It’s no shock to anyone that generally, Chinese people are not so prone to nostalgia when it comes to those years. Yet, in the author’s note, it is written:

In the chaotic changing of the times, normal life remains unchanged, and in normalcy lies a simple harmony, arranged based on the reasonable needs of human nature, producing strength for generations to carry on.

So it is. The crowded by-streets, the scent and sounds of cooking, the bolts of printed fabric ready to be padded for winter clothing. Routine emotions: shame, pride, impatience, brief shocks of almost uncontainable joy. Fu Ping is a work devoted to this—all this and other unremarkable things that serve as evidence for life, carrying on.

Four: do not aspire to be singular. Wang Anyi has solidified her place as one of the most notable authors of contemporary China, and it seems to be this exact desire to avoid distinction that has led to her renown. Like so many Chinese stories told by mothers, grandmothers, and all the ones preceding, this one is in service to lives lived so that the world stands as it is today. In these voices, ordinariness rises to meet the sacred.

Read an excerpt of Fu Ping in Asymptote’s Winter 2015 issue.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and essayist born in China and living in Tokyo, Japan. Her chapbook, How Often I Have Chosen Love, published in early 2019, was the winner of the Frontier Poetry Chapbook Prize. She currently works with Spittoon Literary Magazine, Tokyo Poetry Journal, and Asymptote.

***

Read more about Chinese literature on the Asymptote blog: