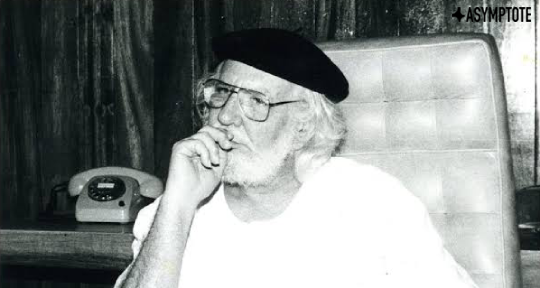

The largesse of Latin American poet Ernesto Cardenal’s political and literary accomplishments is the result of a prolific lifetime of honouring and devoting himself to the humanity of writing. A living legend of Spanish literature, Cardenal turned ninety-five years old earlier this month, and as admirers from all over the world paid tribute, Asymptote’s assistant poetry editor Whitney DeVos was privileged to have attended an event held in the poet’s honour in Mexico City. Below, find her dispatch from the occasion, as well as an overview of his immense accomplishments as a writer, a leader, and a revolutionary.

We at Asymptote would like to wish a happy belated birthday to Nicaraguan-born poet, Roman Catholic priest, liberation theologist, and revolutionary Ernesto Cardenal, one of Latin America’s greatest living writers and likely the most widely-read poet working in the Spanish language today—his literary works have been translated into over twenty languages. Winner of the 2012 Premio de Reina Sofía de Poesía Iberoamericana, Cardenal—known among his admirers simply as el maestro—turned ninety-five on Monday, January 20. Still, he hasn’t slowed down at all in recent years, continuing to make public appearances and releasing three books in 2019 alone: in Spain, Hijo de las estrellas and the single-volume, one thousand-plus page Poesía Completa appeared with Trotta de Madrid, and Canto a México with the Fondo de Cultura Económica (FCE) in Mexico.

The latter served as the occasion for Cardenal’s December visit to Mexico, where he received national honors as part of the “Homenaje de México e Iberoamérica a Ernesto Cardenal” [Mexican and Iberoamerican Homage to Ernesto Cardenal], held from December 3 to 8 in the nation’s capital. There, the Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores [Ministry of Foreign Relations] sponsored a group of activities, including the poet’s participation in several events aimed at different audiences: a two-day diplomatic symposium, “México ante los extremismos: el valor de la cultura frente al odio” [Mexico and extremism: the value of culture in the face of hate]; a small taller [workshop] and Q&A for young poets and students of poetry at the Casa Universitaria del Libro; and a moving public reading from Canto a México in the auditorio de Centro Cultural Bella Epoca, with commentary by Mexican authors Dolores Castro and Marco Antonio Campos, and Paco Ignacio Taibo II, the director of the foundation. On the final day of the visit, during a special closing ceremony, the municipal government declared Cardenal a Huésped Distinguido [Distinguished Guest] of Mexico City, a distinction also bestowed upon Bolivian ex-President Evo Morales, who sought political asylum in CDMX after being deposed in a coup d’état just one month prior to the poet’s visit—Morales also wished Cardenal a happy ninety-fifth birthday via Twitter: “Today, 1925, Brother Ernesto Cardenal, a Nicaraguan priest and poet, but above all, a tireless social advocate and defender of those most humble, was born. We follow his wise words, full of faith and revolutionary thoughts, always.”

Like Morales, Cardenal is no stranger to the devastating effects of foreign political influence, having actively participated in armed struggle against the US-backed Somoza dictatorship (1936-1979) during the failed 1954 April Revolution, and as a member of and foreign ambassador for the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN), a militant nationalist political organization which, in 1979, succeeded in overthrowing Somoza and inaugurating the Nicaraguan Revolution (1979-1990); the ensuing decade would be marked by brutal right-wing paramilitary violence of the Contras, contrarevolucionarios trained by the CIA and covertly supported by the Reagan administration, who killed over thirty thousand Nicaraguans and inflicted severe economic suffering on the country.

Until 1987, Cardenal served as the Minister of Culture for the Sandinista government; remaining in office cost him decades of support of the Catholic church, and only in 2019 did Pope Francis lift canonical sanctions against Cardenal, and reinstate him as an active Roman Catholic priest. His role is remembered for his efforts towards organizing poetry workshops throughout the country based on the model of the campesino workshops of Solentiname, an experimental religious community and ongoing literary and artistic workshop he founded in the late 1960s. There, Costa Rican Mayra Jiménez, who had previously overseen poetry workshops in her native country and in Venezuela, encouraged local, working-class residents of Solentiname to write and share their poetry; the results of her efforts made a lasting impression on the priest. A joint 1982 statement with US-born Allen Ginsberg and Soviet poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko reveals Cardenal’s vision of extending the model to the entire nation of Nicaragua, which they described as “a big experimental workshop for new forms of get-together in which art plays a primordial role.”

In 1994, Cardenal became the first public figure to leave the FSLN, citing then-Secretary General Daniel Ortega’s growing corrupt and repressive political influence. In a statement published in national newspapers, the poet argued that Sandinista revolutionary ideals were being betrayed by a small group, lead by Ortega, who had “kidnapped” the FSLN. The move, which refused to capitulate to the Secretary General’s dictatorial tendencies, was consistent with an important observation made during Cardenal’s 1971 visit to Cuba: “. . . in Cuba, it’s very easy to distinguish the true revolutionaries from the false ones by the way in which they talk of the Revolution: the true revolutionaries criticize it, the false revolutionaries don’t dare to, all errors they deny, they find excuses, they defend them.” Cardenal’s 1994 analysis of the state of the party was prescient: Ortega was reelected President in 2007 and has remained in power ever since. Ortega, like the dictator Somoza—who he, Cardenal, and other Sandinistas so ardently fought to depose—routinely silences, threatens, and kills members of the opposition, employing a range of tactics to censor public criticism, the press in general, and violent state responses to mass civil unrest. In 2018, dozens of students were killed when police began using tear gas, rubber bullets, and live ammunition on unarmed protesters. Protests against the Ortega government continue, as does the administration’s efforts to cover them up; in 2019, Nicaragua was ranked 114th on the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index. Still, ever the revolutionary, Cardenal remains a vocal critic of Ortega and his wife, who is Vice President: “They are in charge of the whole country, up to the justice system, the Police, and the Army,” he told the press in 2017, “I don’t have to say anymore because this is a dictatorship.” He continued, “They have control of all powers in Nicaragua. They have absolute power, infinite, without limits, and that power is against me.”

Having left politics entirely to live and write in solitude, Cardenal’s recent works have emphasized the cosmic aspects of existence, a “pluriverse” constructed capacious enough to acknowledge Darwin alongside spiritual doctrines of faith, and extending rights to all beings, human and non-human. Perhaps not surprisingly, this represents a noticeable turn away from the themes of nationalism and Nicaraguan national liberation for which he is best known in the English-speaking world.

His homage to the country, Canto a México, includes several poems previously published in Homenaje a los indios americanos and Golden UFOs/Ovisnos de oro, such as “Nezahualcoyotl” (1972; 1992), written for the poet-philosopher-king of the Mexica people, as well as newer work like “Tata Vasco” (2011), about the bishop cum national hero who organized artisanal production among the peoples of Michoacán. But more importantly, the book is an exploration of a lifetime of affinities and affiliations, both cosmic and inter-American, in which one’s relation to civic belonging is, as the poet once posited with Ginsberg and Yevtushenko, always in a process of becoming, of blurring out beyond the shifting—and often violent—borders which designate the official location of one’s birth, of one’s parents’ births. For Cardenal, literature has always marked a utopian site in which the existing boundaries of a nation could be negotiated and transgressed, whether by means of militant struggle to end imperialist dictatorships, directing a nation-wide Sandinista literary initiative, adopting various forms of transnational and trans-ideological solidarity during the Cold War, or acknowledging the innate, cosmo-poetic relations between all entities of the pluriverse, living and non-living.

The collection opens with a remarkable preface:

No soy mexicano, pero soy de los muchos no mexicanos que aman mucho a México. Conocí a México desde mi temprana juventud y he vivido mucho en México y como muchos otros no mexicanos de México he sentido a México como mi patria.

I am not Mexican, but I am one of the many non-Mexicans who love Mexico very much. I came to know Mexico in my early youth and I have lived a lot in Mexico and like many other non-Mexicans de Mexico I have felt Mexico as my patria.

There’s a fascinating ambiguity here based on the final usage of “de (from/of) México”, an adjectival modifier which can belong to either the phrase immediately preceding (como mucho otro no mexicanos) or immediately following it (he sentido . . .). One potential reading is “like many other non-Mexicans within/in Mexico I have felt Mexico as my patria.” However, it’s also possible to read the clause as follows: “like many other non-Mexicans from Mexico, I have felt Mexico as my patria.” It is a sort of paradoxical affiliation, at once both national and municipal (México refers both to the nation and to its capital city), but exceeding normative forms of state-based belonging: to be at once non-Mexican and from (or of) Mexico. Cardenal’s use of patria (homeland/native land/country) rather than país (nation) is equally telling, as it emphasizes place, and one’s affective relation to it, rather than the state that delineates and polices the borders around which nations are currently organized. And, indeed, one of the most touching movements at the reading in celebration of Canto a México was one of extra-national recognition. Marco Antonio Campos bestowed upon Cardenal, the self-proclaimed “non-Mexican from Mexico,” the literary equivalent of Huésped Distinguido, precisely by acknowledging the Nicaraguan poet as a vital part of patrimonio cultural, the Mexican literary tradition:

Por los años en que estudió y vivió aquí, le damos las gracias y lo sentimos como uno de los nuestros, a la vez un forjador de cantos y un tlamatinime. Alguien que pertenece a nuestra hermandad de poetas y que en este libro me responde con flores y cantos.

For the years he studied and lived here, we thank him and feel he is one of our own, both a songmaker and a sage. Someone who belongs to our brotherhood of poets and who in this book answers me with flowers and songs.

Not only is Cardenal accepted into—an admittedly phallogocentric—hermandad de poetas mexicanas, but Canto a México is placed on par with revered of pre-conquest Náhuatl Nahua poets whose work predates the contemporary nation of Mexico—including the same Nezahualcóyotl who has inspired Cardenal throughout his career.

It is important to remember, however, that these remain extraordinary, symbolic, and utopian gestures; that to seek Mexico as a place—or even a point—of refuge has become an unpredictable and dangerous undertaking for thousands of Central American amidst the devastating and widespread violence of global capitalism. And those who live or are able to remain in Mexico are witnessing the country’s most violent year in recent history; in 2019, over thirty-five thousand people were murdered and an additional five thousand disappeared. It was one of the worst years on record for femicides: ten Mexican women are killed, on average, each day.

At such difficult historical junctures, the work and life of someone like Ernesto Cardenal becomes a crucial fount of guidance for how to persist and create amid and despite dehumanizing conditions. And indeed, for about an hour and a half on December 5, flanked by Luz Marina Acosta, his assistant of over forty years, el maestro convened with about thirty young poets and writers, including myself, to talk poetry and share his guidance. Eduardo Serdio (b. Mexico City, 1994), a young poet with whom I spoke at length afterwards, beautifully described the room’s palpable anticipation at seeing Cardenal “on the eve of his ninety-five years”:

All of us were young poets invited to the event and we came prepared, each with our own concerns . . . Some spoke of the epigramas, others about the poetry of protest, and some simply how excited they were to meet el maestro. But the questions we’d formulate were forgotten as soon as Father Ernesto Cardenal’s poignant presence entered the room . . . [H]e was transported in a wheelchair and for the great poet to hear the young attendees who, with excitement, resolved to ask [their questions] turned out sometimes to be a rather complicated endeavor . . . Patiently and with much fondness, Ernesto’s eyes lit up. He could not always make out the questions, but made great efforts to listen closely, and the young people happily repeated themselves. His lucidity had not been lost over the years and his eloquence matched his intellectual precision.

Topics discussed included: politics (“lo cabrón es el partido”), Trump, and the threat of fascism; Carlos Martínez Rivas, Roque Dalton and his work (“Sumamente divertido . . . I think he was influenced by me,” to which everyone laughed), as well the enduring influence of Neruda (“sobre todo, era Neruda”); his time at and vision for Solentiname; the Beats, an “inspiration” from whom he learned “nothing”; Cuba; Stalin; God and the current Pope (who he called “a marvel, a miracle”). He asserted no difference between the poetry of men and of women, as both must work towards the same task: “to make life manifest.”

Perhaps the highlight of the intergenerational dialogue—other than a birthday cake and serenade of “Las mañanitas” (the Mexican “Happy Birthday” song)—was his response to the question; “What is the experience of God?” To that, the Father said, simply: “Struggling always to reach Him.”

Throughout his trip, Cardenal stressed the modesty of his decades-long poetic project in the face the difficult realities of the external world. He stated his strong opposition to extremism and hate, but he also made the distinction that “to demand democracy is not extremism, or it is valid extremism.” And it is Cardenal’s political commitment which makes him so beloved among Latin American poets today. Contemporary Nahua poet Martín Tonalmeyotl told me recently that he admired Cardenal’s poetic work, especially Los ovnis de oro, since it tells some of the history of the Mexica people, but “what I like most about him is that he is a revolutionary” Indeed, finding the determination to continue (critiquing and refining) the struggle in the. name of justice is the priest’s most lasting legacy. And it is one of which he is well aware: what worth his work had, Cardenal explained to one of his many crowds, was for “extraliterary reasons”: “for the issues it addresses, for being for the poor and for social justice. To improve the world.” Literature, being of the world, must include the world, Cardenal teaches us. And yearn for other worlds.

I wish to extend my sincere gratitude to Marina Núñez Bespalova, Subsecretaría de Desarrollo Cultural and Pablo Raphael de la Madrid, Director General de Promoción y Festivales Culturales, as well as to Armando Mena, Omar Zapata, and the staff at Talleres de la Casa Universitaria del Libro, all of whom made my attendance at the taller possible.

Numerous works of Cardenal’s poetry and prose have appeared in English translation, including Psalms of Struggle and Liberation (1971), Homage to the American Indians (1973), In Cuba (1974), To Live is to Love (1974), Apocalypse and Other Poems (1974), Marilyn Monroe and Other Poems (1975), The Gospel in Solentiname (1976, 1978, 1979, and 1982; single volume 2010), Zero Hour and Other Documentary Poems (1980), With Walker in Nicaragua and Other Early Poems 1949-1954 (1984), Flights of Victory/Vuelos de victoria (1988), Golden UFOs: The Indian Poems: Los ovnis de oro: Poemas indios (1992), The Doubtful Strait/El estrecho dudoso (1995), Cosmic Canticle (2002), Pluriverse: New and Selected Poems (2009), Origin of the Species and Other Poems (2011), and From the Monastery to the World: The Letters of Thomas Merton and Ernesto Cardenal (2017); the latter is a collection of correspondence between Cardenal and Merton, the spiritual mentor who inspired Cardenal’s own Solentiname. Dream of Solentiname, a remarkable exhibition curated by Pablo León de la Barra including art and writings created by members and visitors of Solentiname, was recently shown in Mexico City and New York.

Whitney DeVos is an assistant editor (poetry) at Asymptote. Her translations have appeared or are forthcoming in Chicago Review, Latin American Literature Today, Copper Nickel, and The Acentos Review. She is also the co-translator, with Valeria Meiller, of A Year in the Sky (Triana Editorial, 2019).

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: