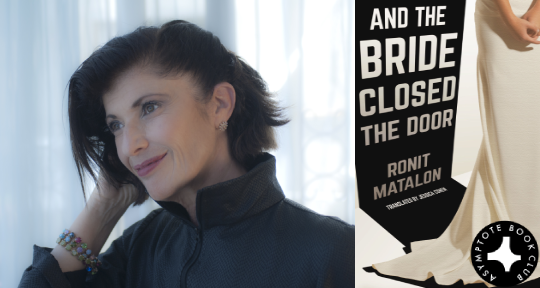

Ronit Matalon is known for her unwavering aesthetic, keen social awareness, and profound insight into family. For the month of October, Asymptote Book Club is proud to present her latest novel, And the Bride Closed the Door. Awarded Israel’s prestigious Brenner Prize a day before she died of cancer, this humorous and tender work captures a chaotic politics in the intimate microcosm of a single family, combining Matalon’s tremendous literary talents with her passion for interrogating identity, both public and private.

An apology and very special thank you to our European subscribers, who’ve had to wait a bit longer than usual for the book to reach them (hence, too, this somewhat late announcement). Though it’s been famously said that “neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays couriers from the swift completion of their rounds,” today’s postal service must fend with much more than the elements; there’s no accounting for logistic mishaps on a global scale! Luckily, thanks to New Vessel and Asymptote’s efforts, Europe-bound copies of the book were finally rescued from postal limbo. Our loyal subscribers will now all receive a lasting gift: a brilliant author and activist writing in her singular language, rescuing empathy from the tumult.

The Asymptote Book Club is bringing the foremost titles in translated fiction every month to readers in the US, the UK, and the EU. For as little as USD15 per book, you can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page.

And the Bride Closed the Door by Ronit Matalon, translated from the Hebrew by Jessica Cohen, New Vessel Press, 2019

Young Margie locks herself up in her bedroom on her wedding day. Save for a brief but damning avowal—“Not getting married. Not getting married. Not getting married”—she falls silent for hours. Efforts to dissuade her prove useless: after pleading, pounding, and heatedly debating the merits of a locksmith, her relatives turn to a company said to quell pre-wedding jitters. The firm’s appointed expert can’t get the bride to open the door, but manages to tap on her third-floor window after an electrician from the Palestinian Authority chips in with his lift truck. Little comes of their gymnastics, however: Margie issues a handwritten “sorry” and retreats. The scant missive and a gender-tweaked excerpt from a classic Israeli poem are her only hints at communication.

One could tout the graces of Matalon’s novella on a number of fronts. Its layered brand of humor—part slapstick, part wit—seeps in and out of darkness with bite, yielding a compact tragicomedy on love and loss. While its characters may flirt with the cartoonish, they never quit the realm of plausibility: their foibles are utterly, achingly human. Its prose, translated by Man Booker Prize winner Jessica Cohen, is a deftly wielded knife.

The author’s approach to longstanding issues in Israeli politics warrants special praise. Her concern for women, Arab Jews, and Palestinians marks the narrative but doesn’t outweigh it—a glowing case of show-don’t-tell. Women are empowered through Margie’s defiance and groom Matti’s acceptance; tensions among Arab and European Jews are captured in the asymmetric dance between the bride and groom’s families (there’s enough to suggest that the former is Mizrahi and the latter, Ashkenazi); the electrician is subjected to the thinly veiled disdain of some Israelis and the bureaucratic whims of their police.

Perhaps most interestingly, though, the book can be read as an allegory of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict at large: a tale of mutually perceived “others” fighting for a home.

Notions of otherness accrue as the story progresses, especially through Matti’s eyes. His perception of his relatives is telling: “these faces in front of him [. . .] perked up and jumped out and gaped with eyes and mouths like crazy glove puppets.” He later recalls a certain “foreign feeling, the alienation from Margie” he’s long experienced. Like most of the family, he’s just as alienated from himself: he wiggles his toes “trying to restore his sense of body” as he suffers a “leakage of himself out of himself,” and when he calls out to Margie, his own voice is “full of strangeness.”

Adding to the novella’s geopolitical motif, scenes of spatial conflict are peppered throughout. Many, of course, involve the titular closed door, but there are others: the bride’s grandmother, Gramsy, is terrified that her apartment’s previous tenant might return at any moment to demand her “legal belongings”; the groom’s father, Arieh, is fighting his brother over their late mother’s house, and his wife Peninit views “compromise as a stinging insult and a grave injury to their honor”; Nadia, mother of the bride, fears that Arieh and Peninit will snatch her apartment due to a standing debt, and that she’ll have to relinquish “what [is] far more costly than the apartment itself[:] her sense of ownership of the apartment.”

Matalon slips allegory into apparently harmless (and often humorous) vignettes as well, always to great effect. In one example, Arieh and Peninit sit in front of Nadia “encircled by several stuffed shopping bags [. . .], piled on top of one another like sandbags in a fortification line.” Nadia’s face is later “tucked in toward [. . .] an estimated longitude”—her blond quiff fluttering above it “like a flag erected on a hilltop by the victor”—and Margie’s idea of a sandwich involves “removing, cleaning, and exterminating” everything inside it before eating the bread.

The author also seems to reference the Israeli-Palestinian conflict’s scriptural underpinnings. Similar to how zealots on both sides point to sacred texts to justify their positions, Margie’s relatives are convinced that her “sorry” and poem hold the key to hers (they tend to fixate on words and meaning in general). Their interpretive stabs are wildly inconclusive, but ours needn’t be: we learn that Margie’s verses are based on part I of Leah Goldberg’s “The Prodigal Son,” itself a riff on the classic Christian parable in which a young man runs off, squanders his inheritance, returns to beg his father’s forgiveness, and gets it in spades. Unbeknownst to the characters in the novella—but not to those of us who’ll promptly look up the poem—Goldberg delivers a twist in parts II and III: the boy comes back unrepentant, his father refuses to forgive him, and his mother tells him to “rise and receive the blessing of [his] father’s loving wrath.”

While the poem plays a complex role in Matalon’s tale (serving, among other things, to further its feminist message) it may well be taken as a parable of Israeli-Palestinian reconciliation; it’s hard not to picture either party as the perceived “stranger” seeking to return to a “forgotten home” and, perhaps less romantically, as one who isn’t especially eager to yield or repent. In such a context, the message of anger cum love—of closeness amid schism—is a powerful one indeed.

Matti makes room for this type of contradiction vis-à-vis Margie. His early bafflement is followed by epiphany: “the locked door [. . .] oddly magnifie[s] what they share” and “her strangeness,” the alienation of which he’s earlier complained, turns out to be precisely why he loves her. The solution to the conflict at the heart of the novella, then, doesn’t lie with locksmiths, cold-feet gurus, or the close reading of poetry (allegorical stand-ins for force, third-party mediation, and scriptural exegesis); it involves the concept of “respect [. . .] without understanding.” Redemption, Matalon appears to be saying, demands something like inclusive ambiguity.

After all else fails with her granddaughter, Gramsy breaks into song. . . and Margie finally turns the key. The old woman’s voice is directed “at many listeners, who all [seem] to gather under [its] broad wingspan, assembling there as though they’[ve] been waiting for a long time for this voice to bring them together.” Ronit Matalon’s is one such voice, aimed at listeners on both sides of the struggle that still haunts her land. And the Bride Closed the Door, her parting song of loving wrath, is arguably her finest. One can only hope that it is heard widely and often, and that the key to peace soon turns in its all-too-rusty lock.

Image credit: Iris Nesher

Josefina Massot was born and lives in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She studied Philosophy at Stanford University and worked for Cabinet Magazine and Lapham’s Quarterly in New York City, where she later served as a foreign correspondent for Argentine newspapers La Nueva and Perfil. She is currently a freelance writer, editor, and translator, as well as an assistant managing editor for Asymptote.