This week’s Translation Tuesday features the Swahili-language writer Mlenge Mgendi. “Comfort Is Expensive” comes from Mlenge Mgendi’s self-published collection Mama wa Jey: Hadithi za Uswahilini (Jey’s Mother: Stories of Swahili Life). Nathalie S. Koening’s nuanced translation captures the different registers of speech in this scatological tale, which weaves indispensable Swahili terms with well-timed slang that, in some ways, feels universal. The speaker captures the anxiety of youth squeezed under community expectations and bureaucratic pressure. Sober, infused with wry humor, and laced with charming off-beat metaphor, “Comfort is Expensive” shows a slice of life that points to the atmosphere of a place and the dispositions that form under specific pressures there.

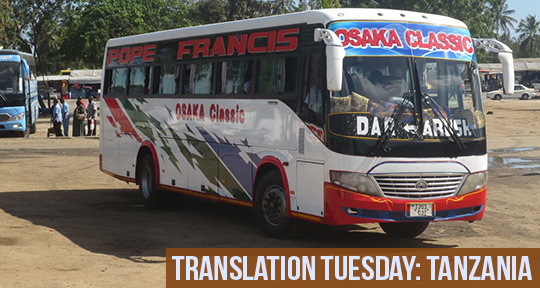

That day, I was coming from school. My stomach, jeopardizing the love, unity and cooperation that had reigned in my bowels for centuries, was causing me real trouble. I had no choice but to hurl myself into a daladala bus and get home in a hurry. Don’t you know? Since our schools have no money for healing all that ails us, students get a “discount” when they ride the bus?

When I got to the stop, a daladala was waiting. It was totally empty, having been outsmarted by another bus that, zipping past like a toothbrush, had plucked up all the fares. As I was climbing in, the konda boy grabbed hold of me. “Hey, you! Stoo-denty! You taking up an actual seat coz you’re gonna pay full price?” The bus pulled away brush-empty, but even then, he wouldn’t let me sit.

Standing for some time, I knew my situation was only getting worse, and the brake I’d been applying to my bowels came close to giving out. A failure in the brake-system and everything in my stomach would rush out with unstoppable speed. As I was standing up alone in a nearly empty daladala, every passenger could see me. Those majambozi rascals had turned me into a public one-man show!

I cajoled the konda, begging him to fathom my predicament—I! His brother from another mother!—but he wouldn’t hear it. “Try to be patient. Your comments have been noted, and, basically, are being addressed. Just have a little self-restraint while the relevant authorities consider your request,” he said.

If it had been just me, I could have been patient, but the problem was, my bowels were unprepared for the crisis we were facing. I took heart. I thought: I’ll pay the full adult fare so I can be seated and avert humiliation. Carefully, I hobbled to the lovely window seat, where I sat down with elegance and grace.

“You’ll pay the adult fare?” the konda said, excited.

“Yes, I’ll pay it.”

He stood on his rights. “Aah! Show me the money and let’s get it over with!”

Sitting dulled the panic of the impatient things inside me, and I felt the pressure on my stomach’s brakes ease up. Lo! Sitting down is great. But being comfortable’s not cheap. At the next stop, the konda laughed his last tooth out when he saw the crowd: a swarm of passengers circling his bus. And he was right. When all of them got on, the bus was packed (bomba!), and the passengers pressed and wove themselves together as if this daladala were the last one in the world.

At my side stood a middle-aged man. That guy eyed my chair, expecting me to give it up to him. I did not. I’d paid full price for that seat, so I saw no reason to. And, considering my stomach’s critical condition, the chance of me giving up my seat to him was only getting slimmer.

One passenger started up the party. “Does that kid have no manners? Can’t he see the grown-up standing there while he’s sitting down?”

Many of the other passengers concurred, especially those who were standing up near me. No doubt they were hoping they’d have a little bit more room when one of them sat down.

The konda raced over to evict me from my seat. “You, stoooo-denty! Cede your place to those who’ve paid full price!” he said harshly. I didn’t want an argument. I showed him the full-fare ticket he’d given me a little while before. He was humbled. I stayed right there in that seat, reveling and fat—eating up the country! I didn’t give a damn about the wrinkly-skins.

A pregnant woman sidled up. Maybe they thought I’d feel some kind of sympathy for her. But I acted like I had no idea what was going on and waited instead for some “good” Samaritans to help her.

Not one Samaritan appeared. All eyes were on me.

“Do you mean to say that you, a stoooo-dent, won’t give up your place even for that woman, who could be your mother?” said the man in the next seat.

But again I just stayed quiet. I didn’t give that woman my seat. She glared at me, and soon other passengers joined in on the defamation. While they went on hurling word-bombs, a looney-tune showed up and decided to defend me. “Let that boy enjoy the fruit of his own sweat!” he said, provoking the other passengers to hisses and more recrimination. But never mind, no he didn’t care, he just went on telling them exactly how it was. “When that boy was forced to remain standing though there were so many empty seats, not one of you leapt up to defend him. Now that he’s enjoying what he got by his own sweat, you conspire against him! Leave him be, let him enjoy himself in comfort. Comfort isn’t cheap! He spent money on this seat . . . ”

I raced off the bus and thereby succeeded in protecting my dignity. I left a heated debate back there. I don’t know how it ended, but these days things are really sweet for me. Now, when I go to school, I pay full fare and I get the pleasure of sitting down in a seat. As I relax and enjoy myself, various people glare at me, hoping I’ll stand up so they can sit down. But once the konda’s gotten his full fare, he doesn’t care what happens. What happiness! What bounty!

Translated from the Swahili by Nathalie S. Koenings

Mlenge Mgendi is a native Swahili-speaker. He was born in Dar es Salaam in 1971, and after finishing high school, trained as an engineer and Geographical Information Systems and Disaster Risk Reduction expert. His first book, Kauli ya Mlalahoi (The Voice of the Wretched of the Earth, Ndanda Mission Press, 1997), was a collection of political satire pieces previously published in the Tanzanian paper The Daily News. He has self-published several short story collections, including Mama wa Jey (Jey’s Mother, 2009), Nihame Bondeni? (Should I Move out of the Valley? 2009) and Ng’ombe wa Maskini (The Poor Man’s Cow, 2010), all subtitled “Stories of Swahili Life” (Hadithi za Uswahilini). He has recently written a story for children, “Demonstration in the Serengeti” (Maandamano ya Serengeti), about mob psychology and riots in the animal kingdom. Into Swahili, he has translated Anton Chekhov’s story “The Bet,” and Shakespeare’s “King Lear.” He is married, with two children, and continues to live in Dar es Salaam.

Nathalie S. Koenings is an anthropologist and fiction writer. She grew up in East Africa, speaking French, English and Swahili. Her ethnographic research is focused on popular geography and the mystical imagination on the island of Pemba, in Zanzibar. Her fiction, concerned with gender, race, and power, and peopled with characters who speak different languages, is often set in East Africa. Her translations of Swahili literature have appeared in Words without Borders, Asymptote, and The New Orleans Review. Koenings also works in the other direction. In 2017, the Caine Prize in African Literature’s Translation Project featured her translation into Swahili of Tope Folarin’s short story “Genesis” (Mwanzo), and, later this year, Mkuki na Nyota Press in Dar es Salaam will publish her translation of oral histories about the building of the Tanzania-Zambia Railway (TAZARA, or “Freedom Railway”) in the late 1960s and early ’70s.

*****

Read more translations on the Asymptote blog: