In this month’s round-up of exciting new translations from around the world, our editors review an artful and intertextual graphic novel from Nicolas Mahler; a lyrical, genre-bending tale of creation and storytelling from Spanish writer Manuel Astur; and a compilation from Gujarati writer Dhumketu, a master of the short story. Read on to find out more!

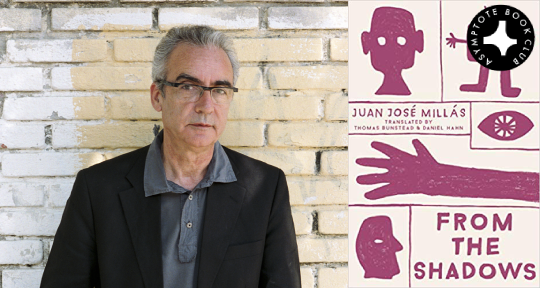

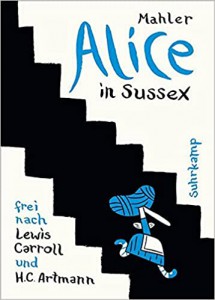

Alice in Sussex by Nicolas Mahler, translated from the German by Alexander Booth, Seagull Books, 2022

Review by Charlie Ng, Editor-at-Large for Hong Kong

Lewis Carroll’s Alice and Frankenstein’s monster make an unlikely combination, but in Alice in Sussex, Austrian comic artist and illustrator Nicolas Mahler brings the two together in his vivid reimagining of a classic tale. The title of the graphic novel makes references to both Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and H. C. Artmann’s parody of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein—Frankenstein in Sussex, suggesting an intertextual playfulness that is further substantiated throughout the work. Mahler’s seven-year-old Alice—the same age as Carroll’s—experiences an adventure as equally nonsensical as the original’s, but her journey is even more rife with complexities, incorporating a wide range of literary and philosophical references. To sum it up, this adventure down the White Rabbit’s hole is a humorous, inventive set, in which Mahler can play with his own literary and philosophical influences.

Readers familiar with Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland can certainly remember the beginning of the children’s classic, in which Alice complains that there are no pictures or conversations in her sister’s book. Mahler’s Alice encounters the same boredom when reading her sister’s copy of Frankenstein in Sussex, and thus initiates the White Rabbit’s invitation into his hole, promising to show her “a lavishly illustrated edition.” Drawn sitting by an infinity-shaped stream, the waters foreshadow Alice’s seemingly never-ending descent down the chimney into a huge house underneath the meadow, as well as the long, elaborated, and bizarre dream that follows. Although the promised book cannot be found on the Rabbit’s bookshelf, the graphic novel actualises it—illustrating Alice’s encounter with Frankenstein’s monster later in the story. It also tries to acknowledge her other desire—for conversations—by letting her meet and converse with other idiosyncratic characters. Both, however, turn out to be anything but desirable for young Alice.

In Lewis Carroll’s original, Alice ponders on her identity after experiencing a series of queer events: “Who in the world am I? Ah, that’s the great puzzle!” Likewise, Mahler’s Alice is confronted with the same crisis, visually represented by Alice falling into the huge, fuzzy cloud of smoke drifting from the pipe of the Caterpillar, who then asks her: “Who are you?” Alice is unable to answer the question, but she also doesn’t make any great effort; her desire to escape is stronger than any liking for strange conversations. A further existentialist twist is introduced when the White Rabbit can only find The Trouble with Being Born by Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran on his bookshelf, and the Caterpillar tells Alice an important thing about life: “Being alive means losing the ground beneath your feet!!!” Such aphorisms are commonly sprinkled throughout the graphic novel—reminiscent of The Trouble with Being Born; the pain of life is treated with levity and amusement, with Alice being tossed around on the Caterpillar’s body, and the Caterpillar’s writhing shifts with his many legs in the air. While Alice is dismayed at losing the ground beneath her feet, the Caterpillar is comfortable with it. Despite being infused with dark humor, Mahler’s style is never overly harsh on his characters; his drawings are delightful, exuding a sense of gentleness. READ MORE…