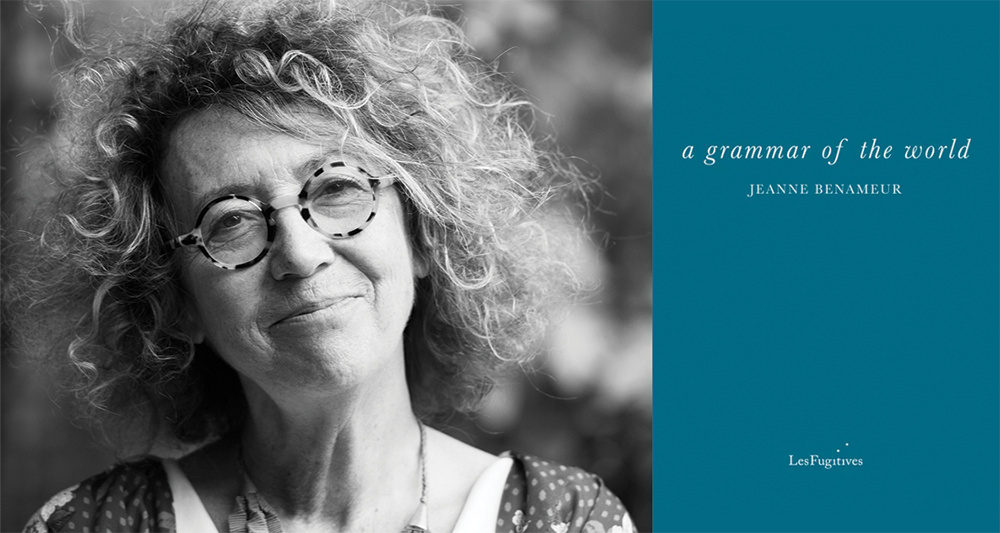

a grammar of the world by Jeanne Benameur, translated from the French by Bill Johnston, Les Fugitives, 2025

The oeuvre of the Algerian-French writer Jeanne Benameur ranges from poetry (Naissance de l’oubli) to an award-winning novella (Les Demeurées) to various works of nonfiction, and in her latest work to be released in English, a grammar of the world, readers are introduced to her voice in verse. The collection details the author’s journey from Algeria—just before the declaration of Algerian War of Independence—to La Rochelle in France where she grew up, a transition explored with the complexity of migration and belonging, and suffused with potent mytho-historical narratives. Through her personal experiences of departure and a complex familial history (with both Italian and Tunisian-Algerian roots), Benameur explores the slow persistence of syntax both in life and in language, which—however displaced and fragmented—can still be reassembled into something habitable and meaningful. The lines of a grammar of the world unfold without punctuation, their sparse cadence travelling over the subsequent pages in soft tidal motions, culminating in a single long poem in free verse, with occasional phrasal recurrences to generate a momentum between its various contexts. Throughout, the voice shifts between ancient and contemporary, depending on whether it is situated in historical precedence or mythical imagery; the speaker gently walks between memory and myth.

We begin with an invocation of Isis, the Egyptian goddess who resurrects her slain brother and husband Osiris, and subsequently produces their son, Horus. According to one of the Egyptian myths, Isis helps the dead enter the afterlife, as she had once helped Osiris by collecting his scattered body parts from across Egypt—and this myth later gave rise to the earliest practice of mummification. In a grammar of the world, it is this act of harvesting and laying to rest that Benameur focuses on, envisioning Isis as the weary sister who bends to rescue what remains in the aftermath of war and displacement. ‘she gathers up what no longer belongs’, writes Benameur: “pieces // she braves that which is scattered’. READ MORE…