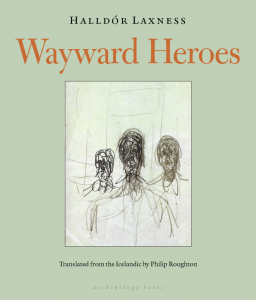

Wayward Heroes, by Halldór Laxness, tr. Philip Roughton. Archipelago Books.

Review: Beau Lowenstern, Editor-at-large, Australia

The process of reading literature in translation is to dip into the perennial pool: possible meanings are compounded by language, we splash and struggle and only when we begin to get on our feet do we realise how much deeper and longer the cave goes. Often great writers see only a tiny fraction of their oeuvre translated for a wider audience—as a reader, we must play a game of guessing the size and shape and clarity of the submerged iceberg from only its superficial crown. Not to mention the person we all know who constantly admonishes us that if we had only read the original…

Iceland’s Halldór Laxness falls into this lamentable category, with the majority of his collection of stories, essays, novels (including a four-volume memoir), plays and poetry frozen in time to all bar those with a blue tongue. Published in Iceland in 1952 as Gerpla, The Happy Warriors was the title of the original, sparsely recognised English translation, though it contributed to his body of work for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1955.