Rosie Clarke (marketing manager): Last month I found that “torturous” reading need not mean “badly written.” I inadvertently spent February with books fixated on death, mourning, poverty, and disturbing desires. In anticipation of her new novel Gutshot, I raced through Amelia Gray’s AM/PM and Threats, in addition to a difficult digestion of Jane Unrue’s Love Hotel, and finally a more peaceful meander through Swiss-German proto-modernist Regina Ullmann’s The Country Road. Together, the intensity of these works had a simultaneously invigorating and exhausting effect.

Gray poses a rather exciting figure to me—of her own fragmentary and boldly inventive fiction, she commented in a recent interview with the New Yorker that “life is such a natural mix of horror and humor that it lends itself easily to the form.” AM/PM is a collection of interconnected vignettes: single page scenes and observations, made on relationships, loneliness, madness, all set in unsettling scenarios of ambiguous reality.

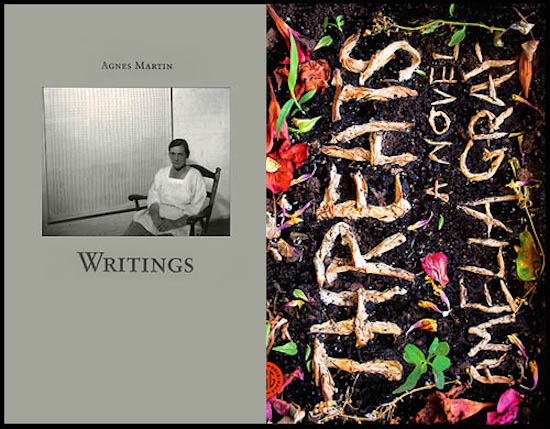

Threats extends Gray’s use of dark humor coupled with a troubling sense of dread. It takes you to a dark place, where loss and solitude manifest in ways almost too real to take. The novel begins with its protagonist, David, watching his wife bleed to death, then sitting with her body for days before intervention. His fragile mental state dissolves, and he loses all concept of time, with short chapters mimicking this to great effect. The titular threats are paper scraps inscribed with poetic, surreal warnings, which David tries to understand. I have never read a book that so effectively communicates the desolation and emotional destruction death can have on a person. This, interwoven with the mystery of his wife’s death and the anonymous notes, makes Threats bizarre and intoxicating.

The addictive confusion of Gray’s book did little to prepare me for Jane Unrue’s Love Hotel. Narrative seems relatively inconsequential, with plot and character information appearing and disappearing without context or explanation. I initially found the book challenging, but it became easier once I allowed myself to give in to Unrue’s dreamlike, fragmentary and surreal “chapters,” and stopped waiting for clues or resolution. The book is erotic without being sexy, disturbing without horror, and holds intense beauty without being cliché—one of Unrue’s most evocative descriptions:

a lake of heavy gilt framed mirrors laid down side by side as if across a surface that the undergrowth combined with what’s pushed up from down below has made uneven all the varying angles of reflection having come together in a glittering array of shattered light.

Before beginning The Country Road, I attempted to read a little about Regina Ullmann’s life. This proved to be difficult, as seemingly very little is known, or recorded, of her. All I could find was that she spent her life as a poor, struggling writer, mother to illegitimate children, and while highly regarded by her literary peers, she received little critical attention. Thematically, Ullmann focuses on mortality, poverty, faith, spiritual awakening, and the passage of life. The largeness of these subjects is condensed, in each story, to the experience of a single person, and their relationships with others and the world around them. Most striking to me is Ullmann’s pantheism, exemplified by her gorgeous analogies used to paint elegant images of nature’s holiness, which contrast with the undercurrent of existential fear in her writing. I hope to see more of her work in translation soon. For now, you can read The Mouse here!

Matthew Spencer (blog columnist): One of the chief merits of Italo Calvino’s Letters is its length. It’s one large but not unwieldy volume, making the book easy to skim. For the English collection, editor Michael Wood wisely chose to publish about 650 of Calvino’s letters, comprehensive enough to get a sense of Calvino’s character as an all-around man of letters.

The Italian publishing house Einaudi released much of this material in the early nineties under the title I libri degli altri (Other People’s Books). This could very well be the title of the English collection too, with its overwhelming focus on literature and not personal matters. Only Borges comes to mind as a suitable rival to the man’s voracious appetite for books and his enthusiasm in discussing them.

Readers interested in the private man should check out The Road to San Giovanni, an excellent and disappointingly under-read collection of essays, the closest Calvino ever came to writing a memoir. But as you might expect, these essays are not straightforward accounts. Calvino focuses instead on the nature of memory and its vagaries. I found the title essay particularly moving: a portrait of his father, a farmer and agronomist, and of Calvino’s time growing up in rural Northern Italy before the Second World War.

I’ve also been reading classic works of science fiction as background for my column on speculative literature, The Orbital Library, published in these digital pages. Dune wasn’t exactly new ground for me. I had devoured Frank Herbert’s pioneering series as a teenager, caught up in the sweeping narrative of Paul Atreides and his struggle to survive on the desert planet Arrakis and avenge himself against the enemies of his family.

Dune regularly takes top position in the canons of science fiction, both with critics and popular audiences, and with good reason. It broadened the genre immensely, famously incorporating ecology and perception-enhancing drugs, just in time for the nascent ’60s counterculture. But it’s also an adventure tale, a sendup of science fiction’s golden age in the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s. Contrived episodes of mortal danger show up, on a chapter by chapter basis, to drive the narrative on. Herbert’s reliance on adventure leads to a great deal of anachronisms, some more plausible—and desirable—than others.

But neither the violence nor the political machinations in Dune had a cathartic effect on me this time around. The book features a flat, demoralizing ending, and the effect is like walking through a baroque palace. Outwardly, there is splendor—too much, in fact. But beautiful surfaces hide an essential emptiness: drafty rooms where inhuman power is at play.

Dong Li (China editor-at-large): I have been visiting artist colonies for the past few months. I was supposed to write poems. I did write things that I thought were poems, and I also read books by artists and about artists on seeing.

The first one was Lawrence Weschler’s biography of Robert Irwin, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees. The book rocked me out of bed, or I made myself believe that Irwin did. The book made me see the evolution of an artist that defies any cheap labels and identities. This is an artist who came out as a painter but abandoned studio art entirely and shifted to installation and public art. This is an artist who talked to scientists and lived in a foreign desert for months on end without talking to anybody. Nothing pulled him back, neither family nor fame. This artist is solitary and gregarious. Weschler wrote the biography by talking to him over a beer or his beloved coke. All contradictions fall into his arms and arsenals and sort themselves out. The subtle field that Irwin creates in his art is one that slowly comes into focus out of its own surroundings. Many museum goers would mistake his installations of light and space as uninstalled rooms. Many do not see. Many are not aware. Irwin is an education to art.

After Irwin, I read Agnes Martin’s Writings. If Irwin is aware of the subtlety of the perceptive pull of life, Martin stares beauty and perfection in the eye. Deceptively simple, every word of hers is true. This should be the Bible in every artistic drawer. “He must listen to his own mind,” dictates Martin. The idiosyncratic path of Irwin suddenly crystallizes in Martin’s words, a clearing indeed, looming out of her grids. The artistic pursuit, at its core, is never materialistic. If we so follow, happiness is “on the beam with life” as every pull of life is exuberantly perfect. Artists, be happy. After Martin, I thought every day was a masterpiece, and loved the shifting songs and sorrows in the open sky.