‘Our political history is a succession of dictatorships.’

—Luiz Ruffato

The fiction of Luiz Ruffato tackles the grave injustices found in Brazilian society: the deep chasm between rich and poor, the endemic corruption, the cheapness of life in the sprawling poverty-stricken peripheries of the major cities. He is the kind of outspoken writer that tumultuous Brazil needs right now. The country is in crisis following recession, a massive corruption scandal and the impeachment process of its President Dilma Rousseff.

It is the poor who will suffer most from this debacle. After just a week in power the administration of acting President Michel Temer began scaling back social policies that the left-wing Workers’ Party had put in place over many years. The Guardian reports that ‘moves are under way to soften the definition of slavery, roll back the demarcation of indigenous land, trim house-building programs’[1].’

Ruffato gave presage to all this in his 2013 speech to Frankfurt Book Fair, presenting Brazil not as an up-and-coming economic success story, but a country in which the shackles of slavery had not been shaken off, describing the abject state of the majority of the population as ‘invisible…deprived of the basic rights of citizenship: housing, transportation, leisure, education, and healthcare…a disposable piece of the machinery driving the economy.’

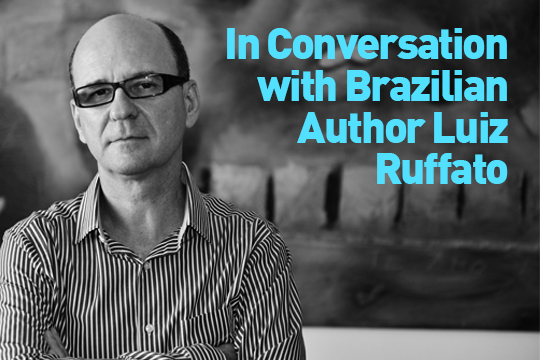

Ruffato is in a position to talk of these matters. The son of an illiterate washerwoman and a popcorn seller, he slept rough for a month in a bus station when he first moved to Sao Paulo, making his subsequent literary success all the more remarkable. His most famous novel, There Were Many Horses, published in English in 2013, has been hailed as a defining novel in the history of Brazilian literature, winning both the Brazilian APCA Award for best novel and the Brazilian National Library’s Machado de Assis Award. In 2016 Ruffato won the International Herman Hesse Prize for Literature in Translation.

Set in São Paulo, a metropolis of over 20 million people, There Were Many Horses roams across the cityscape and its underbelly, investigating the lives of the homeless, the broken, the lonely, the corrupt and the evil. It is an important book for its political and social statements but also a rare example of a novel which engages completely with the concept of the developing world megacity: in characters, imagery, and structure. A series of 69 vignettes which happen over the course of a night in São Paulo, it began as an experiment, an attempt to capture the sprawling city in a way which Ruffato felt traditional novels had not done. Ruffato argues that the book’s experimental form mirrors the splintered infrastructure of São Paulo and the fragmented lives of Paulistas more effectively.

This interview was conducted in two parts. The first meeting happened in Sao Paulo, at the home of Ruffato. The author lives in an old-fashioned apartment block on the quiet crest of one of the city’s steep hills, in the upper middle-class neighbourhood of Perdizes. The narrow marble corridor that leads to his apartment, filled with potted plants and hanging ferns. Inside, the apartment is neat, with few ornaments. Opposite to a shelf of novels and books on art, a sofa sits by a window looking out across the city. The streaming lines of cars, the expanse of blue sky, the poor peripheral sprawl that goes on and on, blurring into the horizon: all of this made a fitting setting to talk about São Paulo itself, the genesis of There Were Many Horses, the challenges of writing about Brazil and developing world cities.

The second part of the interview happened over the internet, after the recent suspension of the President Dilma Rousseff. This time, the author focused on politics and on uncertain future of Brazil. The bold red typeface in which he answered questions was perhaps an indication of the fear he feels for the dangerous position Brazil finds itself in today.

Kathleen McCaul (KM): Tell me how you came to write There Were Many Horses?

Luiz Ruffato (LR): There Were Many Horses, started first of all, like a stylistic exercise. I was thinking the following; for me, to write about São Paulo, or any other megacity, is almost impossible. The idea of a novel is closed, it’s a closed structure, and with a closed structure, you need to make choices, you need to make edits. I thought that these edits were precarious. I was wondering in what way I could get the city in the way that we (Paulistas) get it. I stayed thinking about these questions. The two basic units/concepts of a novel is time and space and I was thinking how does time and space work in a megacity? It’s not the same in a small city—space and time are different there. And space and time in São Paulo and London are different, for example. These two questions were the first things I was thinking and then I started to think how to put these things into São Paulo, how to create a novel, thinking about time and space, set in São Paulo. READ MORE…