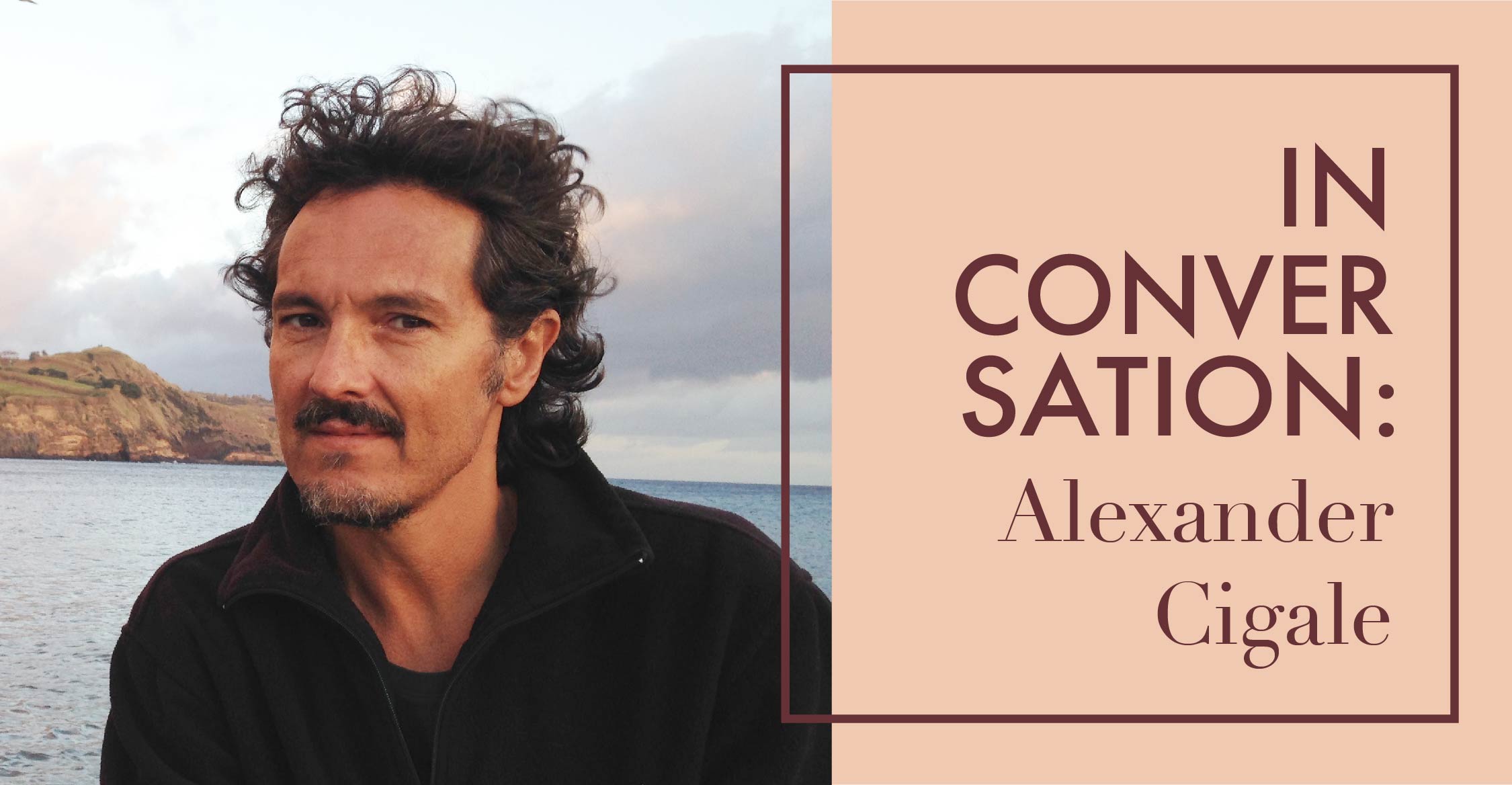

The post-symbolist Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, as dazzling and immediate as he is daunting and complex, is best known in English for the early formal work of Stone (1913) and Tristia (1922). Mandelstam would mature into a poet of visionary modernity in the late 1920s and 1930s. Translator Alexander Cigale is working on an as yet unpublished new volume of selected works by Mandelstam and considers himself part of a Silver Age of Mandelstam translation, after the Golden Age of the 1980s and 90s. While earlier translations established Mandelstam’s reputation in English principally through Tristia and Stone, Cigale chooses to render many of the middle-period “Moscow” poems by Mandelstam, written in the late 1920s and 1930s, and heretofore less well-known in English.

Cigale has also translated Daniil Kharms, a contemporary of Mandelstam and a poet of nonsense and absurdity akin to Lewis Carroll and Samuel Beckett, a poet who seems, at first blush, almost diametrically opposed to Mandelstam in temperament and aesthetic. Both Mandelstam and Kharms have become pillars of Russian twentieth-century poetry. Since publishing a volume of selected works by Kharms in 2017, Cigale seems poised to become an esteemed translator of the greatest Russian poets of the twentieth Century—and, perhaps, of the twenty-first, since Cigale is also at work on the contemporary poet Mikhail Eremin thanks to an NEA Fellowship in Literary Translation.

As a longtime reader of Mandelstam and Kharms, poet Alexander Dickow asks Cigale about the difficulties and rewards of scaling the highest peaks of Russian poetry, and especially that of Mandelstam’s glittering verse.

Alexander Dickow (AD): Alex, you just published in February 2017 a new translation of selected work by the OBERIU (Russian absurdist) writer Daniil Kharms, Russian Absurd: Selected Writings, from Northwestern University Press. Your latest project is a volume of selected poems by the celebrated Acmeist Osip Mandelstam. I’d like to start with a question about the historical situation of these writers who both reached their poetic maturity in the late 1920s or early 1930s. Kharms and Mandelstam were both destroyed by Stalin. How do you think this manifests differently in these poets’ work?

Alexander Cigale (AC): Stalin was cognizant of and acknowledged the genius of Mandelstam (in a phone conversation with Pasternak). I’m not sure Kharms was on anyone’s radar. He outlived most of his friends because the authorities dismissed him for a madman.