Henrik Pontoppidan was one of the greatest writers and social critics of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Denmark, yet his works were only introduced to English readers over one hundred years later. Rife with cultural insight, no-holds-barred excoriations, and teeming with a firm conviction in the potential of the individual, The White Bear—a newly published collection of his two novellas—provides a valuable entrance into a writer deeply suspicious of the hypocrisies and repressions of modern life, one whom Georg Lukács praised as rendering ‘possible a journey through a really vital and dynamic life-totality by its semblance of movement.”

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

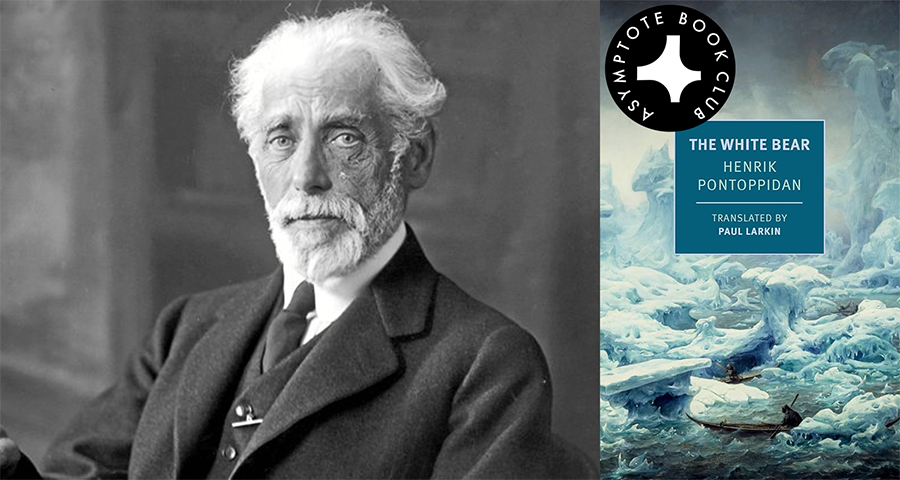

The White Bear by Henrik Pontoppidan, translated from the Danish by Paul Larkin, New York Review Books, 2025

In discussing why we continue to revisit canonical tragedies despite always knowing how they will end, the classicist Bryan Doerries speaks to the worth of spectating on the human capacity for trying. Our myths are full of overwhelmingly fatalistic forces: of destiny, of divine fury, of mysterious arrivals, of certain pains. Yet they are ever-resonant to us not because of any sadistic pleasure to be derived from their characters’ sufferings, but because they have the potential to ‘wake us up to the slim possibility of human agency, of making a choice that averts imminent disaster before it’s too late’. For those in the stories, they walk certainly into their terrible ends—yet for us in the audience, we are given knowledge of the brief moments where things could have been different, where a single turn, or conversation, or even just a few extra minutes of time, could save us and the people we love. Perhaps in taking that understanding back home from the theatre into our own lives, we will have sufficient courage to live not in apathy but in boldness, knowing that there is only one thing that can possibly stand up against chance, and that is choice.

The two novellas that make up Henrik Pontoppidan’s The White Bear are not dissimilar to Greek tragedies, in that they too are concerned with how we can diverge or distinguish ourselves from the long, seemingly straight line of our lives. The titular narrative concerns a pastor in the late nineteenth century who is sent from Denmark into the colony of Greenland. Named Thorkild, this godly man’s position in society is determined at birth; Pontoppidan goes into great description of his appearance and stature, painting the image of a beastly, gargantuan figure whose every feature is an extreme caricature: the face ‘flame-red’ and beard ‘snow-white’, a deafening laugh that incites the howls of dogs, a habit of leaving food remnants across his visage and clothing, a huge body that leaves the furniture in protest—‘born into this world as a freak’. He’s called to Greenland by a kind of divine intervention, based on the perceived unnaturalness of his being, and is sent into exile despite failing by any accounts to pass the necessary examinations. His country rid itself of him with haste, and so in a motion that any expatriate or migrant would recognise, he leaves his native land with little ceremony or resolve, pulled into a crossing that is beyond his control, but that is nevertheless for him to make.

Once arrived in Greenland, however, the nation of ice and tempestuous sun, of crystalline structure and quivering animal flocks—the new world warms to him. Here, Pontoppidan draws a direct contrast between the manmade scriptures that are meant to determine one’s perspective and performance, and the far more resonant patterns and directions of the fierce natural world, which draw from Thorkild an innate animism that coheres him with his environment. Seeing a seal resting on a loose slab of ice, he is ‘gripped by some irresistible instinct’ and grapples for a stone. In the tense and immediate passage that follows, they begin to communicate via their biological rhythms; the seal bobs its head, the man’s heart thumps. After a series of quick exchanges where Thorkild seemingly becomes implicated in the wildness of that landscape, the hand that holds the rock smashes against the seal’s head. The animal meets its death, and man meets his shame.

Pontoppidan is at his most moving and immediate when switching from human perspective to the earth’s own visions, intelligences, and methods. When capturing the landscape, he swerves from a conversational and oral fabulist tone to a more emotionally evocative poetry—which in Paul Larkin’s translation is both elegant and resounding: ‘But gradually this winding inlet was forced into an ever-narrower defile by the flanking, utterly bare rockfaces whose steep sides gave way to mountains rising in peak after peak towards the heavens before disappearing into the clouds.’ One cannot help but be moulded by the environment, but here the environment also moulds itself, growing and adapting its elements in tandem with a million other fastidious factors. In this exchange, everything has its own mysterious motives, but what we see is how it all works together, amalgamating in a veneer of harmony that we can only call landscape. By incorporating the human mind into this mélange, Pontoppidan illustrates the continual tension between a contextual existence and the acknowledgment of our own freedoms—how we sculpt and are sculpted in turn, and how our awareness of such influences is the essential question of being.

When Thorkild eventually makes the decision to return to Denmark, he is an old man who has lived a long and fulfilled life in his enforced exile. However, he finds himself besotted by visions of homeland—though it should be mentioned that these fantasies are in themselves naturalistic and pastoral, and hardly social or cultural. He dreams of ‘the large verdant forests of his fatherland’, to feel ‘the sun-warmed earth beneath him, and the breeze caressing his hair’. There is hope too of community, of a mother or friends that might welcome a prodigal son after a long absence, and when his beloved wife dies, it catalyses his impulse to follow this suspicion—that he can belong elsewhere, after all.

But at its core, ‘The White Bear’ is a fable, and as fables go there is a lesson that must be learned through hardship, humiliation, and conflict. Denmark is unkind to Thorkild; he is far too wild, too much of an alien presence, too accustomed to existing in a larger expanse of wide horizons and endless night, incapable of fitting into the neat rooms and contained social structures of Danish modernity. As opposed to how he had preached in the North, as ‘counselor and comforter’, this church of society is inextricable from its reputation and dogma, more protocol than compassion. When Thorkild advises an elderly parishioner that ‘God just wanted every soul to feel at home with Him’ and that in heaven, everyone gets what they wants, he offers the man a deathbed peace, but sparks a widespread outrage from his peers: ‘To portray Our Lord as some sort of common taproom host and the Kingdom of Souls as nothing more than a putrid alehouse—this was beyond all bounds!’ From then on, this giant man of god becomes further and further alienated from his work and his community; his difference is a source of terror.

When Pontoppidan received the Nobel Prize in 1917, the committee praised ‘his authentic descriptions of present-day life in Denmark’, and the portrait that he paints of his native country is one besotted with privilege and status, restrictively hierarchical but punishingly moral. In the early twentieth century, the nation’s contemporary socialism was just beginning to emerge, but Pontoppidan remains acutely attuned to the divisions that perhaps can never be resolved by political or even cultural shifts. There are fundamental differences between us—whether they are as individual as appearance or behaviour, or as unshakeable as beliefs and convictions.

In the second novella, ‘The Rearguard’, Pontoppidan queries if love and intimacy can ever trespass these separations. As a newlywed couple in Rome, husband Jørgen Hallager and wife Ursula Branth come from opposite sides of the political spectrum; he’s a left-wing painter, adulated in social realist circles, while she’s the daughter of an ultra-conservative politician. There is certainly adoration and erotic attraction between the two lovers, but Pontoppidan continually underscores differences both major and minute in the ways they move within the world. She’s effusive about beautiful things, while he’s reluctantly charmed by them; he’s vehemently opinionated about public discourse, while she’s apathetic; she loves her father, while the older politician stands for everything that Jørgen loathes. Through a series of intensifying dialogues, Pontoppidan gradually builds the disparities within their love affair, setting up the subtleties in how their communication fractures—in how they may be eternally unable to understand one another. Here too is another symptom of tragedy, in which the inevitable becomes quickly clarified, yet those involved in its procession can still seemingly turn around, can still protect themselves at any moment.

At one point, Ursula muses to a confidant: ‘But it’s just because people do not know the real Jørgen Hallager in any way’, before eventually concluding, ‘that doesn’t mean he will always be like that’. It is a line that is likely painfully familiar to us all—this loving in the hopes of changing. There is much to admire in Ursula’s gleaming, even innocent romanticism here, but Pontoppidan casts her as an object of pity. Change, as he diagnoses it, comes from some alchemic combination that perhaps borrows from love, but is never wholly composed of it. As Ursula hopes that the opulence of Rome will cure her husband from his fixation on social issues, Jørgen is writing a letter that complains of how Renaissance frivolities despise of what truly matters: “By my red beard, man, I swear . . . you can walk through a hundred galleries down here without seeing a single reference to ordinary life and the struggles of the common people. Not to mention the human urge for freedom.”

Tragedies simply unravel; we follow them through their passages. Yet just as is with the best of the Greeks, Pontoppidan is careful here to point out the cracks, the impresses, and the hints of what will come—even while the destination looms visibly in the future. Ever the staunch individualist, he advises us that our utmost capacity in the crutches of an ungiving and unslowing universe is simple awareness: the bravery to take notice. To see how you are seen is also to see oneself, and to see oneself is also to see how one sees. Dividing what is circumstance, what is instinct, and what can finally emerge from that clamour—in these stories of devastation, alienation, and misunderstanding, that is the act which ultimately reveals itself as some sort of power.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet, writer, editor, and translator.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: