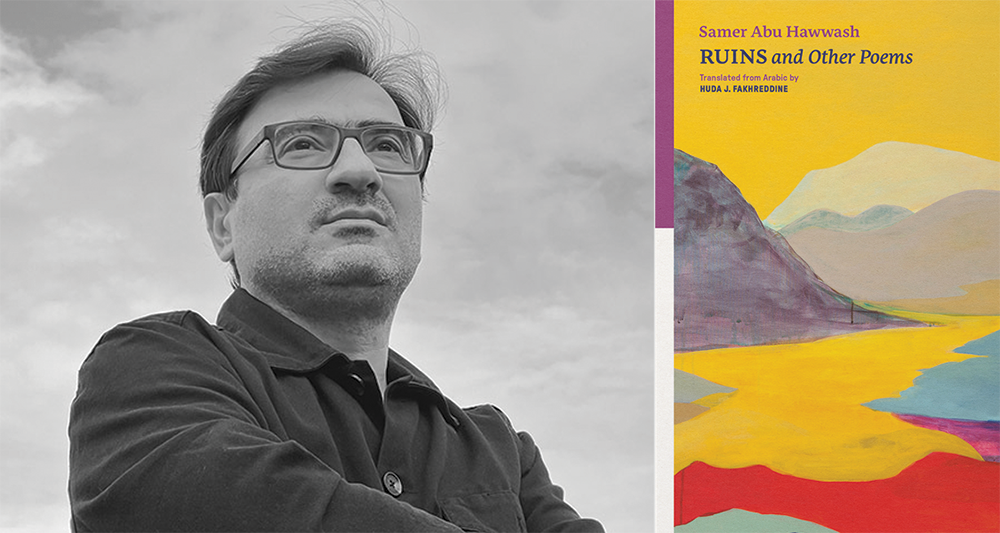

Ruins by Samer Abu Hawwash, translated from the Arabic by Huda J. Fakhreddine, World Poetry, 2025

Translation ferries meaning not just between people, languages, and places but between points in time. It’s a belated art. When the Palestinian poet Samer Abu Hawwash was writing his magisterial collection’s long title poem—first published in Arabic in 2020—there still was a Rafah, a Jabalia, a Beit Hanoun—an inhabitable Gaza Strip. As Huda J. Fakhreddine was translating the poem into English, the Israel Defense Forces were methodically obliterating, body by body and brick by brick, these places and the people in them. By the time World Poetry published Ruins, so much had been lost.

By many accounts, the Arabic poetic tradition begins in this precise spot: facing the absence, in the aftermath. The qasida, the pre-Islamic Arabian ode that gives its name to the generic Arabic word for “poem” and lends a structure to Ruins’ title poem, stages a formalized encounter with the departed. As developed over centuries of oral tradition by Bedouin tribes in the Arabian peninsula, the prototypical qasida homes in on a scene of loss: a speaker arrives at an abandoned desert camp that bears the traces of a lost loved one. Classically, the qasida then moves through a series of proscribed stages—the confrontation with the site of loss, the journey into the desert, the return home—with emphasis on a repetitive, but endlessly revised, inventory of central images: the meadow, the stream, the oryx, the sand. The scholar Michael Sells compares it to jazz. Fakhreddine, in her introduction to this collection, calls it “an edifice of form, an arrangement of sounds and motifs that has stood the test of time.”

Abu Hawwash makes the qasida his own in the three movements of “Ruins,” constructing a poetic terrain where, appropriately to the Palestinian experience, the experience of loss is not bound to one place in time but forms both the ground and the horizon of the speaker’s life. He extends the scene of loss to the entire world, awakening in the opening of “Ruins” to “the mirage of a tear”:

The earth was ravished

by memory ghosts,

a dull glimmer

like an ancient sun,

like a sorrow-worn coat

thrown over

an empty chair.

A harrowing, transfixing poem unspools from here, comprising the bulk of the collection. The way Abu Hawwash’s figuration extends and extends in this passage is representative of the whole: his similes are long and sinuous and tend to see no reason to stop. Later, in the middle movement of “Ruins” (which also highlights Fakhreddine’s magic—a throng of hungry maws!):

Light

throbs

in a stone,like remorse,

like a tree

that sees its roots

in a dream,a throng

of hungry maws.

This motif, and the iterative, self-revising, and self-extending figurative structure that contains it, will come again in the final part of “Ruins,”

Fireflies without light

carve the darkness of this day,

then fall

like old glances

falling

into the emptiness of a room

filled only

with a chair

for memory alone.

Passages like these make me feel as if I’m on a ship at night: I’m being taken somewhere, I’m half-blind and unsteady, but the world is wide-open around me. Sense accumulates in “Ruins” by way of figuration’s world-building abilities, how it binds the disparate pieces of experience in a matrix that accentuates and alters their plain meanings. As foundational nouns like “memory” and “stones” and “birds” and “light” tumble through the long poem, linking up with each other in ever-shifting configurations—as stones “endlessly” fall “into the stalled air / in the mirror of / a well” or as “a bird without memory / or a sky / stands completely silent / at a street corner” — the words begin to bear the traces of all the words they’ve been near. The light on page seventeen is not the same as the light on page ninety-nine.

This construction of a unified field, a zone of language teeming with visions and things, exists in devastating counterpoint to the fact of the loss of the beloved itself, the loss of Palestine. Throughout “Ruins,” Abu Hawwash, in gestures typical of the classical qasida, punctuates his poetic flights with expressions of their inadequacy:

I tell this wall

of my pain and longing,

this wall facing me,

I see it as clear as a needle,but I fear that if I touch it

with a glance,it might disappear.

Everything now

is a touch or a glance

away.

The wall is there; but the wall cannot be touched, not even with a glance; so the wall is not there, will be shattered by the approach of the hand, is not there except insofar as the wall inheres in the word “wall.” Language is, tragically, the only locus of presence in this poem. Abu Hawwash’s speaker must remind himself—and, in turn, us—that everything we’ve encountered thus far is a mirage, a trace, a word in a stanza, an overextended simile grasping desperately for more. Palestine can be spoken to, dreamed of, fought for, died over, but for exiles like Abu Hawwash (born in 1972 in Lebanon), it cannot be touched or seen. This restless motion between the poem’s elaborate metaphysics and its re-encounter with the abyssal fact of physical loss forms Abu Hawwash’s grammar of sorrow.

He picks up this theme in the six shorter poems that fill out the rest of the collection. They’re strange bedfellows of “Ruins,” an eclectic mix that ranges from the incantatory and experimental “From the River to the Sea” to the pointed “A Box of Dates on the Kitchen Table,” which has the speaker debating the ethics and metaphysics of boycotting dates produced in an Israeli settlement (“Aren’t they all ours to begin with, / the soil where they grew, ours, / the water that nourishes them, ours, / the shade they make, ours.”). These shorter ones are not always flattered by their proximity to as extreme an achievement as “Ruins.” The book’s a little lopsided. Six perfectly good poems succeeding a masterpiece.

That said, I’m glad to have them. “From the River to the Sea” seems most of a piece with “Ruins,” offering a fresh way into the house that the first poem builds for us. It offers, over a page and a half of dense text, a litany or roll call of what’s been lost in this most recent iteration of genocide:

every street, every house, every room, every window, every balcony, every wall, every stone, every sorrow, every word, every letter, every whisper, every touch, every glance, every kiss, every tree, every blade of grass, every tear, every scream, every air, every hope, every supplication, every secret, every well, every prayer, every song, every ballad . . .

Through their stark repetition, the words gain a physical heft; in their apparently disordered, syntax-less accumulation on the page, they begin to resemble a pile of stones. Fakhreddine’s rendition in English is tight, musical, and propulsive, launching the reader into the poem’s gut-wrenching end:

every eye, every tear, every word, every letter, every name, every voice, every name, every house, every name, every face, every name, every cloud, every name, every rose, every name, every spear of grass, every name, every wave, every grain of sand, every street, every kiss, every image, every eye, every tear, every yamma, every yaba, every name, every name, every name, every name, every name, every name, every name, every name . . .

Every name. Every name. Every name deserves at least a poem. But should there be 70,000 poems, it still would not be enough.

Maybe, on second thought, these are not the lost artifacts of Palestinian life. I am, after all, the one who has read them that way, in the shadow of death. Maybe these nouns are the totems of existence, the tokens of life: every name and every grove and every friend that persists in the shadow of the Zionist project, that will pursue that fatally faulty dream to the ends of the earth.

I’m reminded here of a line from the Saint Lucian poet Derek Walcott: “The classics can console, but not enough.” The qasida has failure built into its form; the tension between the yearned-for loved one and the negative space of its absence is already accounted for in the poem’s wild similes and stern returns to earth. Even if words are not enough, they may be all that is left.

Michael Sells writes in Desert Tracings, his monumental secular study of the qasida: “The qasida opens onto the abandoned campsite—traces in the sand from rain trenches and tent pegs, blackened hearthstones, ruins (atlál) left by the beloved’s tribe. The traces are silent. Yet they invoke.” The poem can’t bring back a lost love, a lost city. But the right words in the right order can, like a mound of ruins in the desert, stand athwart the emptiness.

Daniel Yadin is a writer, reporter, and translator in New York City. His writing has been featured in New York, The Drift, Publishers Weekly, and elsewhere. He’s an associate poetry editor at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: