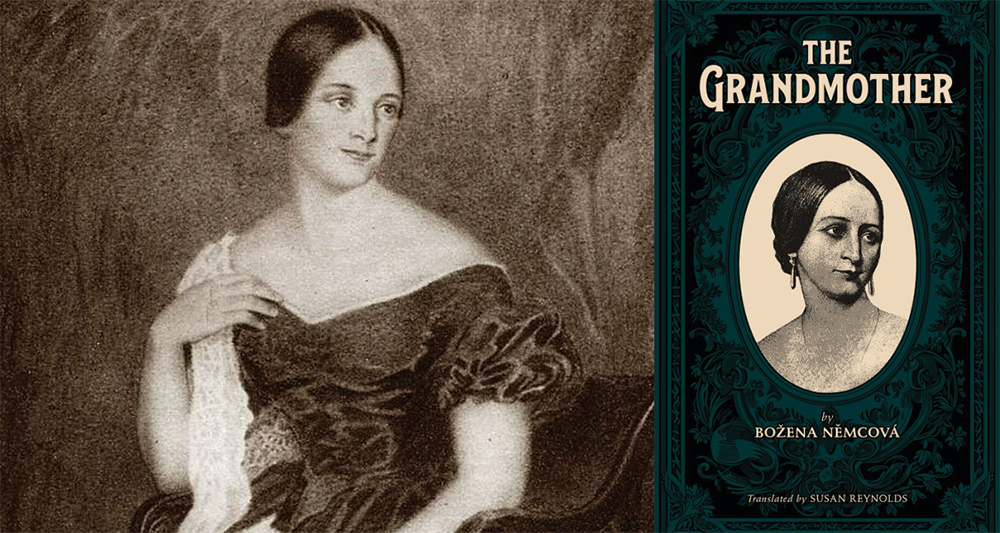

The Grandmother by Božena Němcová, translated from the Czech by Susan Reynolds, Jantar Publishing, 2025

Just over two years ago, Professor Libuše Heczková, director of the Institute of Czech Literature and Comparative Studies at Charles University, Prague, delivered a seminar spotlighting the life, activism, and legacy of Milada Horáková, a Czech politician and staunch resistance member against both the Nazi Germany and Communist Czechoslovak regimes. Horáková’s advocacy was rooted in preserving democracy and women’s rights, defining a feminist as ‘a woman . . . who . . . consciously and responsibly chooses and cultivates chiefly those [qualities] in which there is a genuine, objective contribution to the broadest existing community in human society’. It is precisely this nuanced outlook which is present in Božena Němcová’s Babička, brought to us in English by Susan Reynolds as The Grandmother and released by Jantar Publishing late last year—some one hundred and seventy years after the novel’s first publication.

The Grandmother follows the life of the titular woman who leaves her natal village to go live with her daughter and her family, comprising of four children and a German, non-Czech-speaking husband. The novel’s plot is by no means linear, resembling more a collection of vignettes, with each chapter focusing on a particular episode in the characters’ lives, or imparting a story either from Grandmother’s past or from Czech legend.

Božena Němcová (née Barbora Panklová) was herself born into a German-speaking family in Ratibořice, a small town not far from the Polish border to an Austrian coachman, Johann Pankl, and a Czech maid, Terezie Panklová (née Novotná). When she was still a child, her family was joined by her maternal Czech-speaking grandmother, Magdalena Novotná, to whom Němcová owed her interest in Czech mythology and folktales—yet to assume that this constitutes the sole inspiration of The Grandmother and that the novel is nothing more than thinly veiled autobiography would be as reductive as it would be incorrect. Besides her literary writing, Němcová was a consistent and active member of national and women’s emancipation movements. Her involvement in these causes and her social ideologies permeate throughout her writing, including the deceptively autobiographical The Grandmother.

Though The Grandmother was published in 1855, its plot is set in the 1820s, with some of the tales therein spanning from earlier still. As such, there is a clear tension between the reader’s expectations of the more archaic mindset and values by which Grandmother would live versus the morals she actually espouses; rejecting contemporaneous norms, Němcová casts Grandmother as a vehicle for broader didactics, conveying progressive and liberal reactions to various elements of society.

A notable example is in Grandmother’s open-minded acceptance of her daughters’ marriages to foreigners. At the start of the novel, she shares how she initially felt ‘put out that [Tereza] chose a German’, yet she considers Ján ‘a good, easy-going fellow’ and the grandchildren as ‘[her] very own!’ By the end of the novel, when news reaches her that her other daughter is marrying a Croat, she says: ‘what can I say when you have already chosen according to your heart. . . Why would I stand in your way if Jiří is a good man and you love him? . . . Of course, I did think that at least you would choose a Czech—like goes best with like—but it wasn’t ordained, and I don’t reproach you. We are all the children of one father; one mother feeds us, and so we should love one another, even if we aren’t fellow countrymen.’

It is a strikingly liberal and unprejudiced attitude towards other languages, especially at a time when she herself is communicating in a language of demoted importance—one that is perpetually under threat of, in Milan Kundera’s words, ‘wither[ing] till it is reduced to a mere European dialect—and [its] culture to mere folklore’. Such elements substantiate the historian Jaroslava Janáčková’s description of The Grandmother as a portrait of a ‘woman of the new era [the 1850s]’, rather than a well-intentioned but ultimately uneducated elderly woman from the 1820s—‘a woman in a white kerchief, in peasant’s garb’.

Across Europe, social ideologies of the 1850s were deeply influenced by the aftermath of the 1848 Revolutions across France, Denmark, Ireland, Poland, Germany, Italy, Hungary, and Czechia. These post-revolutionary social ideologies reflected the agitation of the continent, resulting in a marked rise in nationalism and burgeoning iteration of the tension between conservative restoration and liberalism.

In this context, Czech writers and intellectuals sought to establish a Czech literary presence and canon, despite imposed Germanisation from both the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, consequential of the 1620 Battle of White Mountain. This growing nationalist sentiment evolved into the Czech National Revival—a cultural movement spanning the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in which, as Julia Sutton-Mattocks asserts, ‘women were seen as essential to the Revival’s success in their roles as mothers and teachers of the next generation’. Indeed, this tenet would remain crucial for Horáková’s principles of feminism a century later.

However, in considering the necessity for Czech literature to be, in Jan Neruda’s words, ‘raise[d] up . . . to the world’s level of consciousness and education . . . to ensure not only its prestige but its very survival’ in the face of the European hegemony, The Grandmother not only exemplifies the Czech National Revival, but equally engages with other prevalent European ideologies of the time. Throughout the novel, Němcová valorises moral agency rooted in individual consciousness, as well as the concept of freedom from domination. In the fight for freedom from the domination of imposed Germanisation, Grandmother shares how she defiantly reclaimed her own future agency—as well as her children’s—through a sense of patriotism rooted in her language, her religion, her Czech lands:

The general sent for me, too, and told me . . . the boy would go into a military institution, and I could send the girls to the royal institute for women . . . I said that I’d go home to Bohemia, but I wouldn’t give up my children; I would bring them up according to my own faith and in my own language . . . Who would have taught them to love their fatherland and their mother tongue? Nobody. They’d learn foreign languages and foreign ways, and end up forgetting their own blood altogether. How could I answer for that before God? No, no—anyone who is of Czech blood should stick to the Czech tongue . . .

Another important framing intertext lies in The Grandmother’s epigraph, taken from Karl Gutzkow’s Die Ritter vom Geist (The Knights of the Spirit): ‘From this you see, poor humble folk / Are not as wretched as they seem, / For they have more of Paradise / Than we ourselves possess or deem!’. Beyond the shared ideological kinship between Gutzkow and Němcová, the pair also spurn abstract idealism. In a piece of criticism which—like Horáková’s later understanding of feminism—equally focuses on authentic action and production, Gutzkow wrote:

A literature only truly acquires substance when authors treat the works they produce as necessary continuations of their own development, and when they do not seem to take up subjects merely to display their talent through their effects, but rather to prove with them something that is, in itself, a necessity either for the world or at least for themselves and their own individuality.

Grandmother embodies moral insight grounded in daily experience, empathy, and communal care, not in abstract idealism—hence why her progressive views are credible and adhered to like existing social mores. The assertion of Kristla, one of the girls from the village, that she trusts Grandmother as ‘[she does] God’s Law’ because ‘what she says is real gospel truth’ is proof of Grandmother’s community’s eschewal of abstract idealism.

Yet beyond these social philosophies, The Grandmother also remains, at its core, an ode to the tradition and craft of oral storytelling, innate to Czech and Slovak culture. The significance of specific folktales inherited from these national pagan traditions seeps into the very fabric of their identity. In the novel, Němcová describes how the village celebrates various festivals of pagan provenance (still central to the Czech calendar today): Masopust, a Mardi Gras equivalent marking winter’s end, the advent of fertility and health, and the driving away of dark spirits featuring a masquerade parade; Pomlázka or Velikonoční pondělí (Easter Monday), dating as far back as the 1300s, where men visit households and lightly whip girls to bring health, youth, and fertility as spring approaches; Čarodějnice ([The Burning of] the Witches) on 30 April, where bonfires are lit and the young jump over the fire to ensure good health, fertility, and permanently bid farewell to winter.

As for the folktales, Grandmother’s story ‘about princesses with golden stars on their foreheads’ lives on in the 1959 film Princezna se zlatou hvězdou (The Princess with the Golden Star); the ‘hazelnuts in which whole sets of priceless clothes lay tucked away’ can be found in 1973’s Cinderella retelling Tři oříšky pro Popelku (Three Wishes for Cinderella); and the girls ‘pouring to tell fortunes with molten lead’ is seen in the 1999 film Pelíšky (Cosy Dens).

Němcová’s background as an ethnographer—having authored seven volumes of folk tales and stories (Národní báchorky a pověsti) and ten volumes of Slovak fairy tales and stories (Slovenské pohádky a pověsti)—additionally casts The Grandmother as an inherently ethnographic endeavour, chronicling how the Czechs continued to exist in the face of German-language assimilation and hegemony. It is The Grandmother’s ethnographic composition that poses the greatest challenge for translation, and Reynolds’s English rendering does a fantastic job in creating an authentic and engaging narrative voice throughout this collection of parable-like vignettes. Having a voice that commands attention and respect like Grandmother herself is an integral aspect of the translation’s success. Most importantly, Reynolds effortlessly transposes traditional Czech sayings, colloquialisms, and proverbs, striking the balance between fluidity in English and fidelity to the original. In her iteration, the mournful song other village maidens sing on Kristla’s wedding day to Jakub Míla goes from:

Pak až my se rozloučíme,

dvě srdéčka zarmoutíme,

dvě srdéčka, čtyřy oči

budou plakat ve dne v noci

to:

When it’s time to take our leave

Deeply will our two hearts grieve;

two hearts, and four eyes so bright

they will weep by day and night!

Reynolds’s transposition of the song’s rhythm allows the poetry to be organically dictated by the language’s natural cadence, successfully preserving yet another folk element so intrinsic to Němcová’s description of a Czech person’s wedding experience.

But given that The Grandmother is an ethnographic chronicle, there are moments wherein the mapping of one people’s culture, identity, and nationhood into the language of another is unnatural. For example, the choice to translate ‘holka’ (girl) as ‘lassie’ at one point stood out especially due to its clear association as a Northern English and/or Scottish colloquialism, diluting Němcová’s ethnographical mission. But such is the sobering reality and ultimately unmitigable challenge of a target language that lacks a shared cultural lexicon with the original; with no glossary for clarification, the references to ‘Monday’ as a ‘whipping party’ or young boys ‘perform[ing] dances with burning torches’ while the girls ‘jump over the embers’ are not recognisable as acts of Easter Monday and The Burning of the Witches, diluting these ceremonies’ importance and role in Czech national consciousness.

However, as a person who grew up in a family where these myths, folk tales, and ceremonies deeply informed my childhood as much as my identity, my closeness to The Grandmother testifies to the power of the original—but any initial doubt caused by the lack of a shared lexicon only attests to Reynolds’s talent and her translation’s quality. By way of another language, it still evoked the nostalgia of a landscape, culture, and experience personal to me, with sincere pathos.

Božena Němcová’s The Grandmother is unequivocally the gift that keeps on giving. It is a novel of fragments, yet a cohesive whole. Its didactic moments are not moralistic, but the genuine transmission of lessons gained over time. It is an extollation of a whole people whose language, identity, and existence has withstood a subterfuge erasure. It is an oral folk tale transposed into the written. It is perennial. It is the best book the anglophone literary space has never heard of—and one that it owes itself to read.

Sophie Benbelaid is a Senior Assistant Editor for Asymptote based in London and holds two degrees in French and Russian Literature from the University of Oxford. She was acknowledged for her contributions to Robert Chandler’s translation of Other Worlds: Peasants, Pilgrims, Spirits and Saints by Teffi, and was a finalist in the International Translation Contest “Writers of the Silver Age about War” held by The Library for Foreign Literature and the Institute for Literary Translation. Having previously worked as a translation intern with the Institute for Literary Translation, she is an aspiring literary translator and hopes to publish her work in the near future. For now, you can read her writing on her Substack.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: