The first winter after the Second World War was famously brutal across Europe: scarce resources, battered cities, and abnormally cold temperatures that seemed to befit the grief and isolation of the already bereft populace. In distinctive, visually rich prose, with evocative and immediate characterization, Fausta Cialente’s A Very Cold Winter captures both the emotive and physical terrains of this solitudinous and ruptured time in Italian history, tracing the season’s frigidity, desolation, and sense of suspension as it works its way through the city and its people. As our first Book Club selection of the year, it is a novel you can feel in your bones.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

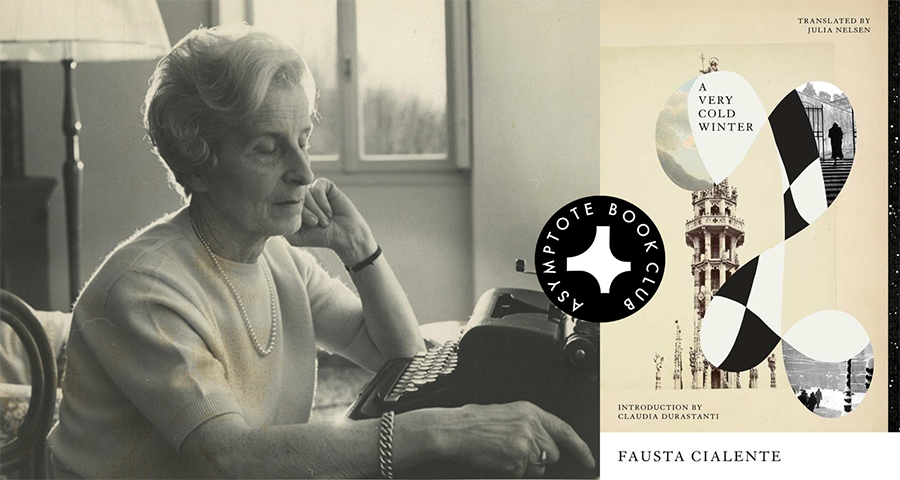

A Very Cold Winter by Fausta Cialente, translated from the Italian by Julia Nelsen, Transit Books, 2026

A woman has been abandoned by her husband—but she doesn’t know why. She now finds herself alone with “perfectly useless” memories, daydreams, idle thoughts, and a family to provide for. To make ends meet, she ends up squatting in a dilapidated third-floor attic with half a dozen relatives.

The premise of Fausta Cialente’s A Very Cold Winter may feel contemporary, but we’re in 1946 Milan: a year after the Liberation, when a city devastated by Fascism and Allied bombings was struck by one of the harshest, longest winters of the century. Originally published in 1966 as Un inverno freddissimo, the novel—Cialente’s first to be written and set in Italy—was met with a curious but mixed critical reception; despite being reprinted a decade later on the occasion of its television adaptation (in 1976, the same year Cialente won the Strega Prize for Le quattro ragazze Wieselberger), A Very Cold Winter has long remained half-forgotten and nearly impossible to find. The novel owes its current resurgence to the Milanese publisher nottetempo, which has reissued several of Cialente’s core works (some featuring scholarly contributions by Emmanuela Carbé, editor of her wartime diary), and to Transit Books, whose publication of Julia Nelsen’s textured translation finally introduces Cialente to a wider Anglophone readership.

In A Very Cold Winter, Cialente’s narrative finds its base and trajectory in the figure of Camilla. Neither young nor old, she is described by Claudia Durasanti in her introduction as “the reluctant matriarch of the house,” or rather, the attic she shares with her extended family: her children Alba, Guido, and Lalla; her nephew Arrigo and his wife Milena; Regina—the widow of Arrigo’s brother Nicola, who died as a partisan—and Nicoletta, her daughter. Two male figures orbit this familial cluster: Enzo, an Egypt-born Italian anarchist, and Rosso, a neighbor from the country house. When we enter the story, Camilla is still actively grieving her lost love, Dario, despite having been on her own for many years. This lutto amoroso (lover’s mourning), as Carbé calls it in an interview with Martina Pala, is the emotional hinge through which Cialente interrogates the notion of abandonment—at the time a disgraceful, even despicable condition for women to be in. Rather than treating it as a literary topos or as a mere occasion for emancipation, Cialente turns up the drama of solitude, making it one of A Very Cold Winter’s key themes by extending it beyond the personal. Much like the attic in which Camilla’s family takes up residence, the city itself also mirrors this desertion; its people, faced with the collapse of social structures, the ever-delayed promise of a better future, and the private devastations of war, are left to mourn their losses alone.

Through Cialente’s spare, elliptical prose, memories of the Second World War are mostly unspoken—an act of omission that is as necessary to survival as it is to literature. As Durastanti notes, “forgetfulness is not a privilege acquired with distance.” This kind of oblivion operates on multiple levels: it determines how war makes its way onto the page, as well as the time and conditions required for it to do so. “The objectivity of war,” Durastanti continues, “is blurred by one’s own perception of time and the wavering faith in what’s truly conveyable through language. Sometimes dreams and nightmares go undercover as useless spies until they resurface in times of peace. How long does it take for a war to get into a novel?” For Cialente—who did not experience the war firsthand in Italy, but as a militant antifascist in Egypt—it took almost twenty years. Soon after the novel came out, she identified “the cold of war” as “the primary cause of the disintegration of human relations”—the interpersonal impact far exceeding material losses. This is reflected in A Very Cold Winter’s frozen present, where reality is hollowed out and destruction and neglect shape the urban landscape as much as the characters’ inner lives. The book offers a stark and uncompromising portrait of debasement in post-war Milan, a city scarred by misery, social erosion, and the loss of both past and future on a social and individual scale. Here, questions of class, inequality, and the bourgeois complicity in Fascism are dispassionately revealed: “As they ambled along the destroyed sidewalks, side-stepping potholes and trenches, she told him about the city that was once orderly and organized, run by rich bureaucrats who spoke in a snobby dialect—and yet were still to blame for the war and all that rubble.” If A Very Cold Winter‘s true protagonist is the cold itself—as Cialente remarked upon the book’s release—its titular winter is an allegory of war’s aftermath, where the living and the dead blur into a single, ghostly presence; time is suspended; and pain, like frost, feels endless, even in the face of new beginnings:

If anyone asked Enzo what he felt most intensely at the time, he’d have said a nauseating disgust at the snow, exasperation at the cold. He could no longer stand waking up to the sight of the dark world that weighed down on the windows before fading into a pale gloom of mist and fog, which turned out to be the sunrise. He couldn’t stand getting out of bed and turning the lamp on at all hours, staring at his reflection in the greenish glare, leaving the house to find the sidewalks choked with icy snow, let alone the silent white flurry that relentlessly cloaked the half-vanished universe, which had lost every plausible shape.

Throughout the novel, cold is Camilla’s primary adversary, and yet it permeates her very being. Her coldness looks like failure, existential solitude, detachment, and rigor, but also like a cultivated disillusionment—a disposition she seems to have actively pursued, especially when it comes to her relationship to love and romanticism:

She often rummaged through the memories of married life, searching for a reason why he’d left; for her part, all she found was an enormous amount of love, a love as naïve as it was useless. Only recently did she consider it all a waste, her naivete a kind of clumsiness—perhaps that was her fault.”

As writer Danilo Scioscia describes, the cold is “a latent force” that “exasperates character until it reveals itself in its fundamental pain.” However, it is precisely through Camilla’s individual characterization that Cialente confronts postwar Italy’s particular state of moral and affective desertion, within which Camilla’s independence is both vital and exemplary: “A woman on my own. That’s what I am. But that irrepressible feeling of being alive, of expecting something from life, never left her.” A harbinger of quiet, rebellious heroism, Camilla embodies both a stereotypically feminine spirit of self-sacrifice, as well as a pragmatic ability to mend the bonds of solidarity and trust within the fragmented network of lives revolving around her. Drawing on her feminist political consciousness, Cialente articulates the persistent state of crisis at the heart of A Very Cold Winter without the grandiosity and clamor that characterized most male-led wartime narratives of the time (including much of the literature of the Italian Resistance, whose limitations Italo Calvino notably acknowledged in his 1964 preface to The Path to the Nest of Spiders). She favors instead an intimate, nuanced depiction of social and affective reality that doesn’t shy away from human idiosyncrasies.

Camilla’s complexity is further brought into focus by her moral rigidity and occasional self-righteousness. Her highly critical inner monologue often bursts into the novel, disrupting a narrative otherwise dominated by free indirect discourse: “If not for Camilla, who’d gone out of her way to take Regina in . . . the others wouldn’t have welcomed her—not out of spite, no, because none of them were spiteful after all, but out of indifference, selfishness, plain and simple.” As she oscillates between upholding social and familial codes and succumbing to their pressures, Camilla finds herself sustaining an identity that is not entirely her own. Her critical eye, an expression of this inner conflict, becomes in turn particularly stinging in the judgement of the other female characters—with the ultimate target of this scrutiny being Alba. She is described as having been “born all grown up, jaded from the start, always so glum and pouty, even as a kid, snubbing the small joys all children are after.” As the only character to permanently leave the attic, Alba seeks a modern, more immediate form of emancipation in Rome, where she turns to prostitution before meeting a premature death in a car accident, alongside a client who had become her partner. Her pursuit of autonomy stands in stark contrast to Camilla’s, and through this critical lens, identity and destiny are made to coincide, casting Alba’s very nature as a sentence: “And look where it led—such a violent, romantic end.” There’s no way to tell whether this judgement belongs to Camilla or to Cialente’s authorial voice, yet it is far from a mere clash of female archetypes: the friction between Alba and Camilla reflects that of a transition between two eras, prefiguring what Carbé describes as the “historical fracture” imposed by progress—which would come to define imperial and colonial legacies across Europe and the Mediterranean.

In tracing the novel’s political underpinnings, Scioscia observes that “the winter of conscience can only turn into spring by rejecting the roles assigned by the old world”—the same world that “legitimized Nazi-fascism.” The passing of the seasons provides a key to understanding Camilla’s trajectory; in an apparent change of course, she returns to the country house with the arrival of spring. It is there that, when she is offered the opportunity to reconcile with her husband, she chooses otherwise. Instead of mending a broken past or embodying the role history imposed upon her, Camilla finally transforms her solitude into a site of true autonomy, affirming herself as a whole being. Through this radical refusal, Cialente contends that the labor of self-determination is the essential prerequisite for restoring a conscience that is at once personal and shared—the prelude to a collective awakening that, to this day, is yet to come.

Veronica Gisondi is a writer and translator working between English and Italian. Her practice spans nonfiction, poetry, and criticism, with a focus on contemporary art and culture. She is the founder of Incunabula, an independent editorial project for the dissemination of Italian writing in translation. Its inaugural release, Letters to the Blind by Camilla Salvatore, was published in 2025.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- Announcing Our December Book Club Selection: The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi and Sharawi the Adulterer by Belal Fadl

- Announcing Our November Book Club Selection: The Competition of Unfinished Stories by Sener Ozmen

- Announcing Our October Book Club Selection: Time Tunnel by Eileen Chang