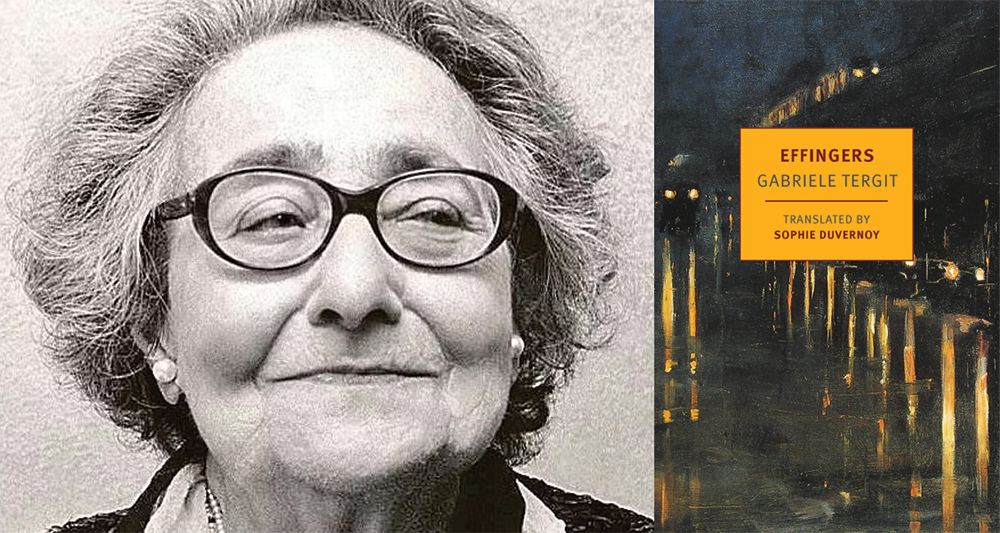

Effingers by Gabriele Tergit, translated from the German by Sophie Duvernoy, New York Review Books, 2025

There are few endings more shocking than that of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, when, after hundreds of pages of convalescence and long discussions, its hero is called down from the Swiss sanatorium to the battlefield:

Thus he lay; and thus, in high summer, the year was once more rounding out, the seventh year, though he knew it not, of his sojourn up here.

Then, like a thunder-peal—

Mann refuses to complete his sentence, specifying only that the thunder-peal “made the foundations of the earth to shake”; it is too well known what it portends. It is the Great War, and Hans Castorp must rejoin the world before he can leave it. Suddenly, from one paragraph to the next, he is in the trenches, and Mann can’t help but describe the scene. Castorp is in the mud, beneath the rain, a town on fire behind his back, the enemy before his eyes—and “What is it? Where are we? Whither has the dream snatched us? Twilight, rain, filth.” Whether he’s ill or not, the question that Mann has asked over the course of the novel, no longer matters: he’ll live or die on the battlefield.

That’s the trouble with writing a novel before history did us the courtesy of ending. Mann began The Magic Mountain in 1912, when all of Europe knew war was coming, and sat sagely at dinner tables discussing it. Two years later, that war had begun, and the world had ended. The novel Mann had begun could no longer be finished; what ought to have been the main performance could no longer be more than a happy prologue to the swelling act. The Magic Mountain was published in 1924. There was no more kaiser, there was no more tsar, there was no more Europe.

Gabriele Tergit’s Effingers was conceived in the new world, eight years later in 1932. Things were different, the great break was over, the war was long behind her, and so too were the revolutions that followed. There was no longer any such thing as stability—but there was time to write a novel. Tergit had no illusions about the past or future of Germany when she began Effingers; born in Berlin in 1894 to a wealthy Jewish family, she had worked as a court reporter during the rise of Nazism, reported on Nazi trials, and was a Jewish woman in Germany. It would’ve been impossible not to know her country’s propensity for anti-Semitism of the most vicious and dangerous kind, but it is one thing to know and another to see. Efforts to contextualize and compare the Holocaust—to point to its historical precedents in European colonies or the philosophical and scientific beliefs that made it possible—are useful correctives to the myth that the concentration camp was a total aberration in the course of Europe’s beautiful history, but this kind of analysis has a way of flattening, missing the fact that to be a German Jew in 1939 was to witness an utter devastation of what had theretofore been thought possible. So to be Gabriele Tergit.

Effingers was to be a book for the Jewish reading public in Germany, and by the time it was completed, that public no longer existed. But a novel is not necessarily scrapped and completely reconceived whenever it starts to look irrelevant, and thus Effingers stands as a document of pre-war Germany, with its closing hundred pages or so turning to World War II and the Holocaust. Tergit begins in 1878 with Paul Effinger, iron-foundry employee and engineering student. He returns to his family home in Kragsheim, a typically German town in Franconia, in the hopes of setting up a factory there to manufacture screws, inspired by his years of engineering and by his brother Benno, an industrial success in London who has abandoned Germany as a “country where merchants are despised as profiteers.” But Kragsheim, like Germany, like Europe, is a town caught between political-economic arrangements, governed by a mayor but ruled by a prince. The only land available for factories is too near the palace, and “His Majesty . . . resides here in the summer, and our merchants, as your father knows well, depend on the court’s patronage.” So Paul must turn to Berlin, where the borders are swelling with industry. He sets out to secure a loan but is unsuccessful with both his uncles—prominent bankers in Mannheim—as well as with the banking firm of Oppner & Goldschmidt; they’re cautious after the panic of 1873, and neither believes in the future of manufacturing. Eventually, Paul goes into business with a man he met on the train to Berlin, Schlemmer, who designs engines made by hand, no two alike. Thus the first conflicts emerge as a question of economic modes, personified respectively by the cautious banker; the artistically minded handicraftsman; the ambitious and intelligent budding industrialist. None of these are mere incarnations, and Paul especially is a fully realized personage, but in this moment their roles are more schematic than embodied, more illustrative than narratively inevitable.

Indeed, Tergit’s writing is precariously close to the line separating a novel from an allegory or a history. When young Herbert, Paul’s nephew, is forced by a mysterious dark figure to embezzle money from the family firm and subsequently flees to America, it reads more as a morality tale—or at best an intriguing anecdote—than a personal tragedy. It is hard for it to be anything more, because the Effingers are a closed-off people, in which such a family shame is not to be spoken of, and because the unspoken (or the unwritten) does not exist in Effingers. Even when Paul’s daughter Lotte, one of the rounder characters in the novel and a distant stand-in for Tergit, falls in love, it is revealed only through her actions: “This, Lotte knew, was a declaration of love. She became a completely new person. She memorized her French vocabulary, prepared her Shakespeare for class, even though it was very hard, and cleaned up her drawers. She darned her socks.” The style remains uniformly objective, with frequent dips into free indirect discourse, but rarely with a wide or surprising enough gap between the omniscient narration and a character’s thoughts for such excursions to register especially strongly.

So we follow from Paul’s eventual success in starting his factory to its inevitable failure, which is incurred through no fault of his own, but collapses due to one of the crises that has now become obviously recurrent under the new marvelous economic system. The panic of 1873 looms over the beginning of the novel, and here comes another already. In this world, the success of a man is determined not by his diligence or ambition but by global factors—the size of a harvest and irrational reactions to changing prices.

The family saga, moving beyond Paul, begins in earnest with the arrival of Paul’s brother Karl at the factory, his own firm having been bankrupted. There have already been a few detours from the Effingers over to the families of the bankers Oppner and Goldschmidt, and the reason becomes clear when Karl marries Annette, the daughter of Selma Goldschmidt and Emmanuel Oppner. The union of two families into one banking firm foreshadows the union of those two and the Effingers. For the Oppners, Karl at first appears as a backwater upstart, a potential threat to the quasi-aristocracy of this urban Jewish clan, who discuss the rise of science over the laws of religion in a room watched over by an academic portrait of themselves, “dressed in splendid seventeenth-century Flemish costumes seated at a long table in a columned hall.” Soon they come to accept this factory owner, the son of a rural watchmaker, and to allow his name as an attachment to the glittering prestige of their own. Times, in short, are changing.

First Karl marries Annette, then Paul her younger sister Klara; the pace increases as children are born, four to the former (James, Herbert, Erwin, and Marianne), one to the latter (Lotte), and the differences between the Effingers and Oppners grows to become more a matter of personality than nationality (as the grandparents had feared it would be). None of the children take after the Effingers—perhaps they might if they were raised in Kragsheim, among its people, but they are raised in Berlin among Berliners. All the sons meet with the type of scandal previously associated with their mothers’ families; whereas an Effinger had responsibly thrown away a youthful affair the moment he understood that it was time to build a career and a family, an Oppner is entirely prepared to throw his family and life away for the sake of his mistress—only coming to his senses under great urging from his family. James even finds himself enamored with the same woman that his maternal uncles have had affairs with: the beautiful actress Susanna Widerklee. Herbert, meanwhile, embezzles from the family firm and must shamefully move to America. Erwin becomes a communist. Such acts would have been nearly unthinkable for any of the earlier generation of Effingers.

The daughters are of more interest to Tergit, and they too show more of their mothers’ family influence. Marianne and Lotte are presented in obverse, and they remain close throughout their lives, each rejecting the acceptable ways of living as a woman at the turn of the century—Marianne more consistently, Lotte’s imitatively. Both adopt the sentimental version of left-wing politics typical of young people, involve themselves to varying degrees in the women’s movement, and enter romances that are treated with far greater subjectivity and profundity than those of the older generation, for whom love was only a pleasant coincidence in the pragmatic matter of choosing a spouse. Lotte’s would-be lover (for whose sake she darns her socks) is taciturn and deeply pained: “Phrases such as ‘I can’t live without you,’ or ‘You know that I’m mad about you,’ flowed like water from the lips of the other boys. But Ludwig Heesen remained silent.” He later kills himself, one of several suicides in the novel. Marianne’s analogous relationship is with a young man named Martin Schröder. They spend hours together in private discussion of capitalism and Thomas Mann, and though the family assumes this to be a courtship, Marianne doesn’t dare hope; Martin, it turns out, would never marry a Jew. In any case, the old forms, signs, and paths no longer obtain: “This man comes to our house every day, and you spend hours with him. Generally, this leads to an engagement,” Annette tells her daughter. “Why would he come every day if he didn’t like her?” she asks Erwin.

For a young woman of the time, it was particularly daring to say no to the life set out for her, but Effingers communicates the triumph of the task with Amalie Mayer: leader in the women’s movement, daughter of the bankrupt former owner of the Oppners’s home, and a one-time potential wife for a poorer, more rambunctious Paul Effinger, before his nerves were settled. Amalie has never married, has found an independent life for herself, and now encourages the youth of Berlin to follow her into freedom. It’s a thrilling suggestion for Lotte and Marianne, but a frightening one for the rest of the family; Amalie may have done as well as she could for her circumstances, but these are not the Effinger girls’ circumstances, nor are they decisions to be taken lightly. A man might take a mistress, have a child with her, leave the country for a while, send her some money, and continue to have a successful banking career and marry a pretty young thing (as does Theodor), but if a woman is so much as seen entering a man’s apartment, or writes an amorous letter, she will carry the shame forever; she may even have to go to Paris and become an artist, like poor Sofie Oppner. The question of how to live in this new century—whether to follow Ibsen, or Marx, or Herzl—is of great concern to everyone living through it, but the stakes of experimenting with such new ideas are far higher for women. Lotte’s dear uncle Waldemar comes closest to understanding: “. . . none of us can truly tell you that it’s best to study, or help the poor, or marry a rich man, or marry for love.” But in the end even a brilliant, thoughtful man like him can only throw his hands up with the world’s least useful platitude: “But one thing is certain: You must forge your own path.”

Tergit comes from the German school of New Objectivity, “whose aim was to depict contemporary culture and society with cool dispassion,” as Sophie Duvernoy writes in the introduction to her translation of Tergit’s first, much more successful, novel, Käsebier Takes Berlin. New Objectivity was a response to a response, as so much of art history is. While German expressionism imitated the mad-cap, fast-paced technological, political, and military developments of the twentieth century’s beginnings, it is essentially romantic, attuned to and expressive of powerful emotion and subjective experience; the New Objectivists, however, saw the same developments, as well as the First World War, and decided it would be more adequately depicted and responded to with straightforward, surface-level (but not superficial) depiction. Tergit attempts to remain a New Objectivist through Effingers, but the surface is simply inadequate to meet the Nazis. Before their rise, the novel’s most distinctive stylistic feature is the use of refrains, both within chapters:

What a beautiful spring day, that Saturday in March 1887! How sweet the air was at ten o’clock in the morning! . . .

What a beautiful spring day, that Saturday in March 1887! How sweet the air was at eleven o’clock in the morning! . . .

What a beautiful spring day, that Saturday in March 1887! How sweet the air was at one o’clock in the afternoon!

And across them: “As usual, Black people picked cotton, kerchiefs on their heads. As usual, the farmers in Canada harvested wheat.” Unfortunately, these sentences, at least in English, don’t have enough poetry to carry a novel, and call too much attention at the beginnings of chapters to work their way into the unconscious. They’re successful only as an expression of Tergit’s depiction of cyclical and slow-moving historical forces. In general, the bulk of the novel is most appealing when viewed at the highest level, in its structure and ideas.

As an actual reading experience, Effingers comes into its own when Tergit is freed from the New Objectivist strictures she has set for herself. The rise of Nazism does not bring with it an entirely new work, but there is a definite shift in tone and pacing, beginning with an appearance of Adolf Hitler himself. Lotte has moved to Munich to study when the power of Nazism is first expressed. There, a friend advises her: “You must go to the Krone Circus sometime—there’s a dangerous madman performing there and you must go see him.” One might picture the quintessential expressionist figure of Dr. Caligari, but when they enter the tent, they find someone much more dangerous and much madder. Hitler stands before the crowd in the dark tent, rousing them with one question after another. “Who has robbed you of your money? . . . Who brought us into the bondage of debt? For whom are you laboring in your field?” he asks the crowd, to which: “The voices came slowly, one after the other, from above and below, from one side and the other: ‘The Jew—the Jew—the Jew—the Jew.’” Hitler, Lotte’s friend recognizes, “is breathing new life into the old belief in devils and demons. He simply calls them Jews.” Hardly a subject for cool dispassion.

Here, the sentences become more manic (“Beggars, fear, unemployment—puppets, all of them, jerked about by the brutal hands of demonic statesmen to serve senile machinations!”) and the paragraphs more broadly associative. There’s a greater tendency toward elevated language and dramatic, religious metaphor:

In vain had the Nazarene sacrificed himself; in vain had the Jews cried, ‘Praise be to peace’ . . .

Two more decades—then wolves would stalk through Paris, and jackals and hyenas would roam through London. Everything would be dead, decayed, gone. A dove with an olive branch in its beak would fly away in search of Mount Ararat.

These are still only deviations from Tergit’s typical objective style, but they are increasingly frequent, and considerably more beautiful than anything that comes before them. Like Mann, Tergit is “noways minded to indulge in any rodomontade; merely led hither by the spirit of . . . narrative.” In part, this language is no doubt an echo of the verbiage of fascism and its fervid, apocalyptic worldview, intoxicating even to its victims; Tergit does not succumb to such impulses for the other major historical or personal events in Effingers, such as the First World War or a death in the family, but nor does she alter her style over the sake of the novel to simply reflect the historical moment. These moments of intensity more powerfully reflect the power of the contemporaneous. It is easy to look back on history soberly, not so easy when it is happening as you write.

World War I represented the end of a way of life, but for Tergit, and to any German Jew, the Holocaust was the end of the world. We may follow Erwin to a prisoner-of-war camp in World War I, but when Paul is sent to a concentration camp, he simply disappears. This is not a moment to be reckoned with, a problem to be solved, or an opportunity, no matter what the Zionist settlers of the book may believe; it is wholesale devastation. By the end of Effingers, the streets of Berlin are covered in rubble and empty of Jews. The Germans have lost the war, but have carried out their genocide to great success. The refrains make one last attempt at asserting the continuity of things—“What a beautiful spring day, that Saturday in May 1948!”—but it is hard to believe in the bountiful harvest now.

Henry Gifford is a freelance copy editor and translator.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: