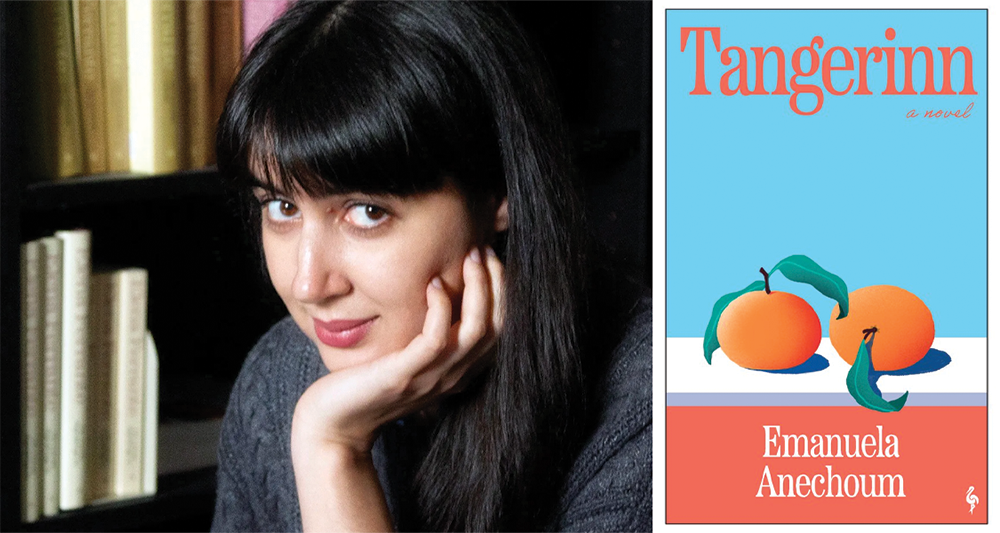

Tangerinn by Emanuela Anechoum, translated from the Italian by Lucy Rand, Europa Editions, 2026

When Mina, the first-person narrator of Emanuela Anechoum’s debut novel Tangerinn, returns to her childhood home in southern Italy after the death of her father, she is argumentative and defensive. She fights with her sister Aisha who picks her up at the airport—about hair removal, head scarves, who knew their father best. Though some of this prickliness could be due to grief, her pre-loss self has already been established as someone quick to judge, who has shored up a levee of self-defense. Mina readily admits to herself that she is a knot of “inadequacy and fear” and is most on edge trying to answer the question of who she really is. Though this query is always loaded, it is particularly so in this novel that takes on the weighty contemporary topics of cross-generational immigration and the social digital landscape.

The beginning of Tangerinn takes place in London and shares resonances with Vicenzo Latronico’s Perfection, published in English earlier this year. Like Mina, Latronico’s couple have moved from Italy to northern Europe and define themselves by their curations—what brands, plants, colors, furniture, and neighborhood they live in. But while the insecurities of Perfection remain mostly placid below this veneer, Mina dislikes her acquiescence to this powerful, social dictate, which is represented by her roommate/mentor/idol Liz. Before Mina receives the call about her dad’s death, she and Liz are having a conversation about envy, at which Mina thinks: “I envy everyone, all the time. I constantly envy people who are beautiful, rich, happy, sure of themselves. I’m full of venom for other people’s privilege, and I also envy their merits. I hope Liz loses everything she has.” Yet Mina must have Liz as her friend, because only Liz—the influencer who has everything—can be the reassurance that she is getting her life in London right.

When Mina is called back to southern Italy, she brings along her London self to the one she had sought to escape by leaving. “The house was still the same,” she observes—also meaning, so is she—and: “[T]he person I had become was irrelevant here.” Mina’s eccentric mother Berta is as checked out as she was in Mina’s childhood, while her dad Omar has left his bar, called Tangerinn, to his daughters to manage. It is here where Mina most feels her father’s presence, and it is also where she can begin to confront herself honestly.

Anechoum isn’t interested in approaching the problem of self-definition linearly; Tangerinn meanders through scenes of childhood, London, and the present, much like how our minds are layered with selves. In part two, the narrative straightens slightly when Mina recounts, in the second person, her father’s story of leaving Morocco: “You had ferocious ambitions that you were ashamed to reveal. Ambition, like everything else, was mocked in the neighborhood.” Omar had grown up among five other siblings in poverty and always dreamed of getting away, and through these memories of memories, Mina interrogates the shared experience of leaving. “The choice, in reality, wasn’t yours. This thing too, like all the other things, was happening to you. It had already happened. You couldn’t stop it.” Mina could as well be observing this about herself. Omar leaves Morocco after a violent protest, and despite saying that he is going to take care of his family so that his sister doesn’t have to live with a domestic abuser, he never returns.

Mina begins to relax when she helps Aisha at Tangerinn and meets Nazim, her equal in skepticism and someone whose identity Mina is quick to pigeonhole (“So you’re educated, rich and a white savior?”). But despite growing up rich and privileged, Nazim is quick to admit that his work as a cultural mediator with Doctors Without Borders is about his own need to feel good, as well as being a way to avoid intimacy. Aisha observes that Mina and Nazim are the same: “You both come and go with this restlessness and then think you’ve discovered God knows what and that your truth applies to everyone.” Nazim is honest, confident, and less concerned about what people think of him, perhaps as a result of his more privileged upbringing. He challenges Mina to reconsider who she thinks she is against the backdrop of home.

Without the influence of Liz and the city’s pressures to like what everyone likes, Mina loses a bit of her bite. Despite the rules and restrictions of her small town and her family’s imperfections, she starts to appreciate the complexity of the people and their situations—her sister’s choice to wear the hijab, her mother’s swimming naked after distributing her father’s ashes. Love for Nazim begins to stir inside her as she notices: “His touch was warm and light. I felt his rough fingers down to my bones.” Mina has defined herself so thoroughly with her departure and its catalyst of past suffering—the small-town racism and the worthlessness it incited; her self-absorbed mother; her quiet, immigrant father—that the other ways her home defined her were reduced. It is only after giving it up for the shallowness of London and Liz, after facing herself, that she begins to let her life have meaning.

To want to become in accordance with the desire of others is a natural part of growing up, but to accept who you are, where you came from, your parents for all their imperfections, how you were hurt and caused hurt, is a major accomplishment in becoming an adult. Like Latronico’s Perfection, Tangerinn is a sort of millennial coming-of-age novel—a story of blooming beyond the social images and pressures that can get confused with a meaningful life. While Latronico tells this story with an omniscient and distant narrator, Anechoum gets as deep inside Mina as prose can get, and Lucy Rand’s translation expertly sharpens Mina’s subtle transformation.

It is interesting that these two Italian novels should come out to the Anglosphere within the same year. They are both deeply critical of the digital social landscape, the American image-making machine of popular culture that moves and devours quickly, but the more I think about it, the more this origin makes sense; despite its firm regional traditions, Italy has absorbed and adapted culturally over centuries. The exodus of young people from the south has lately altered the cultural landscape of the country yet again, weighing it down with the elderly. Italians seem perfectly poised to ask questions about who we are when we immigrate to where the opportunities are better and what “better” even means. For Omar’s generation coming from North Africa, southern Italy was included in the dream of Europe. For Mina’s, it’s a backwater to be traded for northern Europe’s cities.

At Omar’s celebration of life, she thinks: “Without anything outside of me changing, without cutting my hair or taking peyote—I had become who I am.” To become oneself, neither here nor there, not right or wrong, but to embody the whole mixed-up middling complication of a living messy being, requires a process of interior reckoning. Mina makes clear that turning away from the images and identities that she has curated isn’t pleasant, but by the end of Tangerinn, I was relieved that she did—and could even become a bit more pleasant herself because of it.

Amber Ruth Paulen is a writer and educator living in rural Michigan. She earned her MFA in fiction at Columbia University and is currently writing a multi-generational novel about the struggles to keep one family farm running and the costs of an inheritance.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- Grief and Knowledge in a Dying World: A Review of Inn of the Survivors by Maico Morellini

- Translation Tuesday: An Excerpt from Baba by Mohamed Maalel

- Thinking through Labour: A Review of The Arcana of Reproduction by Leopoldina Fortunati