Upon the premiere of Youssef Chahine’s Cairo at Cannes, the Egyptian critics in attendance resented its unflinching portrayal of the city’s poverty and density, claiming it as a derogatory and inciting the film’s eventual ban. In The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi and Sharawi the Adulterer, author and screenwriter Belal Fadl takes a similarly undaunted look at the capital: its swarming underbelly, its suffocating divides, and its unrelenting pressures that bloom both tragedy and absurdity. Written in a captivating style that listens carefully to the city’s manifold ranges, Fadl is determined to pull back the curtains, putting a middle finger up to politeness or grandeur, and drawing instead on chaos, comedy, and linguistic richness to portrait a Cairo full of adrenaline, be it from laughter, thrill, or the sheer will to survive.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

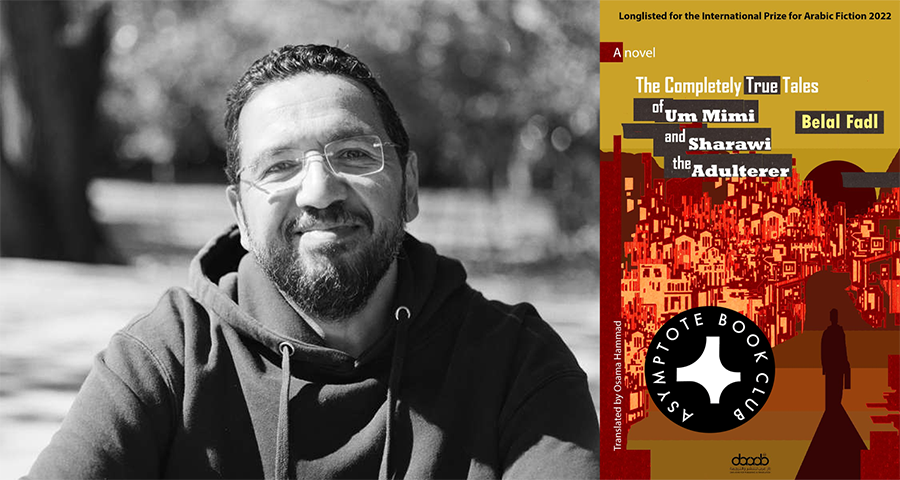

The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi and Sharawi the Adulterer by Belal Fadl, translated from the Arabic by Osama Hammad, DarArab, 2025

Belal Fadl’s The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi and Sharawi the Adulterer announces itself with a provocation and never retreats from it: “Whenever I tell my story, I say that what led me to live with Um Mimi were two Polish breasts with unparalleled nipples.” From this opening confession, the novel signals that nothing sacred will be protected from language, and nothing obscene will be softened for the reader’s comfort. But this is not bravado for its own sake—Fadl’s novel is built on a wager: that obscenity, vulgarity, and excess are not moral failures of language, but its most truthful registers when class humiliation, bodily precarity, and institutional contempt are the subject. To read The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi (or to be more accurate, to read it in translation) is therefore to confront an ethical question: how does a translator render a voice whose truth depends on its refusal to be clean?

The novel’s narrative arc is deceptively simple (almost cliché). It’s 1991, and a young man from Alexandria arrives in Cairo to study media at Cairo University, determined to escape an abusive father and a suffocating household. His grades win him admission, but his finances dictate his fate. Having endured a humiliating stay in a flat with “decent, pious, and religious young men who knew God and had learned the Quran by heart,” he is evicted for attending an R-rated film, and ends up renting a room in the ground-floor flat of Um Mimi, a retired madam, on a nameless lane known only as “the street behind Casino Isis.”

What follows is less a plot than a prolonged exposure. Um Mimi’s flat is a space without privacy. The door does not close, the air is thick, rats and geckos share the room, and her son Mimi—a blond, alcoholic mechanic drifting between stupor and menace—occupies the living room like a permanent threat. This flat serves as a vivid chronotope, a pressure-cooker where the social hierarchies of Cairo compress and collide. It is here that neighbors, pimps, policemen, and fathers gather to pimp out their daughters, forming a small economy of prostitution.

Ultimately, the narrator’s year in this world ends as it began. At the close of the academic year, he escapes back to Alexandria, leaving Um Mimi’s alley behind—but not without promising another descent in a future volume. This skeletal summary, however, does not capture the novel’s real drama, which lies not in what happens but in how it is narrated, the relentlessness by which the narrator implicates the reader in his ordeal. As readers, we are not mere observers; we are pulled into the narrative, confronted directly by the narrator’s challenges and provocations. Fadl strikingly deploys a talkative, self-conscious first-person narrator who refuses to let the reader remain a passive observer. The narrator anticipates objections, corrects assumptions, apologizes for digressions, and addresses the reader directly:

I don’t want to waste your time by detailing my brief stay in the dull Nasr City flat or to tell my story about the Cairo International Film Festival and its spicy movies, which managed to escape the censor’s scissors.

In one particularly disarming direct address, he draws the reader deeper into the narrative:

You should know that I did not elaborate on the name of the street where Um Mimi’s house was located because I had a desire to delay introducing you to Um Mimi herself.

The narrator’s engagement operates as both an authorial strategy and a mechanism of intimacy, compelling the reader to confront the messiness of the world he describes. Drawing on an established narrative practice of breaking the fourth wall, Fadl weaponizes the convention with coercive intimacy, in which the reader is denied the safety of aesthetic distance and forced to sit beside the narrator on Um Mimi’s filthy couch, to listen to Mimi’s drunken monologues, to smell the food, the bodies, the decay.

The novel’s humor—often obscene, often cruel—does not simply entertain; it sharpens the immediacy of the scenes described. Laughter, therefore, functions as both a shield and a weapon. It subverts the power dynamics at play, turning the tables on authority by exposing the absurdity within the squalor, and becomes a nervous reflex, a survival mechanism in the face of what cannot be turned away from. The narrator is unmistakably middle-class: educated, idealistic, and largely confident in his moral values, even as it is tested. His gaze thus renders Um Mimi’s lowlife simultaneously grotesque and fascinating—a judgment that does not arise from filth alone, but from the dissonance between inherited values and lived necessity. This tension produces both satire and unease, and never fully resolves.

If voice is the novel’s engine, language is its terrain. The original Arabic text of The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi unfolds in a volatile mixture of registers: classical Arabic infused with Qur’anic and literary intertextualities; flexible, spoken fusha; sharp Egyptian colloquial; and finally, words long excluded from the Adab|belles-lettres—explicit sexual terms, blasphemy, insults aimed at bodies, lineage, and belief. This linguistic cocktail is not decorative. Fadl moves effortlessly from elevated metaphors to street expressions and then plunges into the profanity of pimps, drunks, and policemen. The result is a language that feels alive precisely because it is unstable. It mirrors the social reality it depicts: a world where dignity and degradation coexist in the same breath, where no single register is sufficient. Some Arab readers and/or critics have accused the novel of overindulging in its lexicon of insults. It’s a fair assessment, but the more pressing issue is not quantity; it is function. In The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi, obscenity is not a shock value, but the everyday speech of power relations. People curse to dominate, to humiliate, to survive. To strip this language of its bluntness would be to strip the world of its logic.

This brings us to the translation’s most difficult question: how to translate a book whose ethical core depends on vulgarity? Arabic obscenity does not map cleanly onto English. What sounds brutally casual in Egyptian Arabic can come across as either grotesquely exaggerated or oddly muted when rendered literally. The translator faces a double risk: sanitizing the language and betraying the social truth, or overcorrecting and turning lived speech into spectacle. Fidelity here cannot be lexical. It must be tonal.

The task of the translator, then, is to preserve discomfort. The English reader should feel invaded, unsettled, occasionally repelled. Not because the translator seeks to shock, but because the novel’s moral force resides in that unease. Euphemism would merely reproduce the middle-class cleanliness the narrator himself clings to as a shield. “I was forced to touch what I had spent my life believing I should never even look at,” he confesses.

English profanity saturates faster than Arabic; its bluntness can tip into caricature. The translator must therefore calibrate constantly, choosing effect over equivalence, making use of practical markers to guide this delicate balance. A rhythmic jolt, such as an unexpected turn in tone or pacing, can signal preserved discomfort without excess. Another cue could be abrupt code-switching, which can maintain the rawness of dialogue while preventing the slip into stereotype. By implementing these markers, translation can honor the original’s intent and integrity. This operation is evident in the following excerpt:

It was easy enough to close my eyes and mouth to protect them from backsplash. . . However, I couldn’t close my nostrils. The heavy smells that couldn’t rise to the level of where I’d been standing now overwhelmed my nose. My ears were shocked by the mortician barking, “I said get me some real men to wash the body, not green boys who can’t hold themselves up. Get this sissy boy outside. . . Let’s get this fucking bleak day over with, shall we?”

The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi could be mistaken for poverty porn or grotesque spectacle. Yet the novel’s filth is not there to make readers feel superior; it exposes the systems—economic, familial, institutional—that produce it. In his intricate translation, Osama Hammad’s language repels just enough to prevent voyeuristic comfort.

Although the novel presents itself as a social rather than political novel, power saturates every page. Policemen protect pimps in exchange for sexual access; terror-era paranoia becomes a tool of intimidation; the state’s contempt is etched into the very geography of Cairo, in streets unworthy of names. Salvation arrives not as freedom but as transaction: marriage, money, and exile. As Fadl writes:

She couldn’t imagine that Samia would ruin her dream so that Rehab would have no choice but to marry her husband’s elderly friend and live with her sister in that faraway country, where Samia hated the suffocating lifestyle and the crushing loneliness.

The interplay of state, police, and patriarchy forms an unholy triad that reinforces the oppression and subjugation flowing through the city’s veins, making the novel’s political undercurrents impossible to ignore. Yet the novel resists turning these dynamics into slogans. Its politics are embedded in scenes, jokes, and humiliations. In this sense, the novel advances Fadl’s broader project by saying what journalism and cinema—hemmed in by censorship—cannot risk saying aloud. Here, language tells the truth without mitigation, even when that truth is ugly.

One of the novel’s most unsettling aspects is its refusal of moral catharsis. The narrator does not save anyone. When tested, he fails; when threatened, he lies; when the year ends, he runs. His escape, returning to Alexandria and his mother’s care, feels both cowardly, necessary, and honest. This retreat is symptomatic of middle-class disengagement, reflecting a broader societal pattern rather than a purely personal failure. The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi offers no fantasy of redemption through suffering. Its refusal of closure extends to the ending itself, which gestures toward future installments without resolving the ethical contradictions it has exposed. “This was my final encounter with Sharawi the Adulterer and his entourage,” says the narrator, “and the beginning of my journey to Samka Alley, which I’ll tell you about later if we live long enough.” This is not a promise of progress, only of continuation.

The Completely True Tales of Um Mimi and Sharawi the Adulterer is not a “polite” novel; its achievement lies in transforming squalor into testimony and humiliation into narrative authority. Fadl writes as a storyteller, a hakawati in the fullest sense, using satire not to distance himself from pain but to make it bearable.

Ibrahim Fawzy is an Egyptian writer and literary translator working between Arabic and English. He holds an MFA in Literary Translation from Boston University and both a BA and MA in Comparative Literature from Fayoum University, Egypt. Fawzy’s translations have been featured in various literary outlets. His accolades include a 2024-25 Global Africa Translation Fellowship, a 2024 PEN Presents Award, and the 2024 Peter K. Jansen Memorial Travel Fellowship from ALTA.