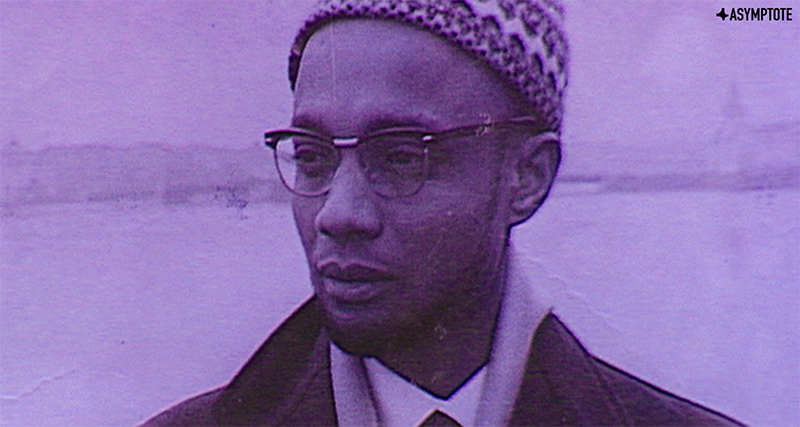

Poet, revolutionary, scientist, politician: Amílcar Cabral took many roles throughout his extraordinary life, including leading the nationalist movements of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. Admired for his staunch ideals and his uncompromising vision of pan-Africanism, many of his ideas continue to be found in anti-oppression rhetorics and movements all over the world. In this essay, Bethlehem Attfield takes a look at his legacy—one that has spread far beyond the African continent—fifty years after his nation’s independence.

This year, Cape Verde is celebrating a special milestone: the fiftieth anniversary of the nation’s independence. Yet, the celebrations actually began the year before, in honour of what would have been the hundredth birthday of the country’s founding hero, Amílcar Cabral (1924–73). Cabral was a political leader who founded the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), and led an armed struggle to free both nations from Portuguese colonial rule. While he is best remembered as a prominent anticolonial figure across Africa, Cabral also left a powerful legacy through his writing, poetry, and cultural ideas, many of which are collected in the volume Resistance and Decolonization, translated by Dan Wood.

Particularly intriguing are his theories concerning culture; he regarded the promotion of national spirit among the rural peasantry, whose lives remained unaffected by imperialism, as vital to national liberation. However, in terms of language use, he differed from most anticolonial leaders who condemn the destructive impact of colonial language on the cultural fabric and psyche of the colonised people. Instead, Cabral argued that the colonial suppression of cultural life in Africa was ineffective, writing:

Except for cases of genocide or the violent reduction of native populations to cultural and social insignificance, the epoch of colonization was not sufficient, at least in Africa, to bring about any significant destruction or degradation of the essential elements of the culture and traditions of the colonized peoples.

Elsewhere, he also pragmatically explained how he values the Portuguese language for the purposes of scientific and technological progress in Guinea-Bissau and the Cape Verde Islands—at least, until Creole becomes sufficiently developed to replace it:

We of the Party, if we want to lead our people forward for a long time to come—to write, to advance in science—our language has to be Portuguese. And this is an honor. It’s the only thing we can appreciate from the tuga, because he left his language after having stolen so much from our land. Until an actual day in which, having deeply studied Creole . . . we could begin to write in Creole.

As a keen advocate of writing in African languages, I instinctively disagree with Cabral’s view, which diverges sharply from Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s perspective that language is a reflection of culture, especially in its oral traditions and literature, which capture a whole range of values that shape our identity and our understanding of our place in the world. However, last month, I had the opportunity to attend the sixth Biennial African Studies conference in Cape Verde, and despite my reservations about Cabral’s views on culture, I was excited to participate in the sessions focused on his work. Then, on the flight to Cape Verde, I was fortunate to meet Rahkii ‘Hyp’ Holman, who was heading to a screening of a documentary he made in honour of his first cousin twice removed—Amílcar Cabral—at the same conference. He invited me to attend the screening and agreed to answer some of my questions afterwards.

Hyp is a proud fourth-generation Cape Verdean-American. Growing up, he embraced US culture, and it wasn’t until his twenties that he started to truly appreciate the activist lifestyle his parents and relatives had been part of; his parents actively participated in social justice movements, and as he paid closer attention to their efforts, the importance of the old photographs in their home became more meaningful—like the picture of his grandfather with Amílcar Cabral. This led him to wonder: ‘Can you inherit genes that enable you to stand against social injustices?’

After this, he began visiting Cape Verde more frequently and also became more interested in learning about Cabral. During these visits, he captured memorable images and recorded videos of some of his meaningful interactions, including the first time he met Cabral’s daughter, his second cousin. News of the conference then inspired him to create a documentary; even though he had never made a film before, he saw it as a perfect opportunity to showcase his footage and honour Cabral’s legacy.

While learning about social movements in the US, Hyp discovered how activist practices worldwide can influence each other; for his film, he wanted to explore how Cabral has inspired Black movements in the US. Recalling an encounter with Angela Davis, he noted that the celebrated author herself had a connection with Cabral, and once he started the project, people eagerly introduced him to more high-profile activists who had been inspired by Cabral’s work, spanning across generations. In the film, people of all ages appear, and Hyp stated: ‘It was important for me to show the kind of solidarity the African-American movements had with Africa.’

Hyp believes that archiving and continuing with the intention of forging connections between global movements matters. He plans to use the film to inspire and educate, working in collaboration with an organisation that uplifts groups of young people impacted by the carceral system in San Francisco. His role includes creating a Restorative Justice curriculum for youth groups, many of which have been affected by incarceration directly or indirectly. Usually incorporating hip-hop into his curriculum, Hyp prompts his students to analyse the lyrics, reflecting on their expressions of various social constructs, such as the impact of male figures in their lives, or how capitalism influences families.

Historically, in many African precolonial societies, knowledge was passed down by the griots: West African storytellers, poets, and musicians. Although the griots’ role is usually hereditary, transmitted through generations, Hyp created his own lineage of storytelling by exploring how legacies reflect and surface in unforeseen places. According to press reviews, his film, Honoring Amílcar, demonstrates how Cabral’s revolutionary ideas, principled actions, and core values have influenced the work and political commitments of those featured in the film. Moreover, the film effectively emphasises that the issues Cabral championed throughout his life—aimed at liberating African society from Western imperialist domination—remain as relevant today and resonate with other social movements. For example, Vern Cromartie’s presentation at the conference highlighted the links between Amílcar Cabral and the Black Panther movement.

Unfortunately, regarding Cabral’s views on language, I noticed that his hope that Creole would gradually replace Portuguese did not materialise. Portuguese remains the official language of Cape Verde and the sole language of instruction in schools. Most Cape Verdean literature is still predominantly written in Portuguese.

Despite these reservations, it was truly inspiring to listen to prominent African scholars and policymakers discuss under the conference’s theme of ‘African Responses to Global Vulnerabilities: Building Hope for the Future‘, examined specifically through five keynote speeches by Toussant Kafarhire Murhula (President of the ASAA), Carlos Lopes (Developmental Economist), Kelechi Kalu (University of California), Cristina Duarte (UN Special Adviser on Africa), and Isaias Barreto da Rosa (UNESCO Representative), as well as various interdisciplinary sessions. In the closing ceremony, Murhula emphasised that challenges in Africa should not be seen as normal or inherent to the continent, but as valuable opportunities for learning, innovation, and growth—a pivotal thought as one looks towards Cape Verde’s next fifty years.

Bethlehem Attfield holds a PhD at Birmingham University, researching the translation of African-language literature with a focus on Amharic Fiction. Her translation of The Lost Spell, a novel written in Amharic by Yismake Worku, was published by Henningham Family Press in March 2022, and was shortlisted for 2022 TA First Translation Prize by Society of Authors. She received the Global Africa Translation Fellowship Award 2023 for her project which aims to build a more inclusive African literary canon, beyond the hierarchies that currently relegate literature in indigenous languages.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: