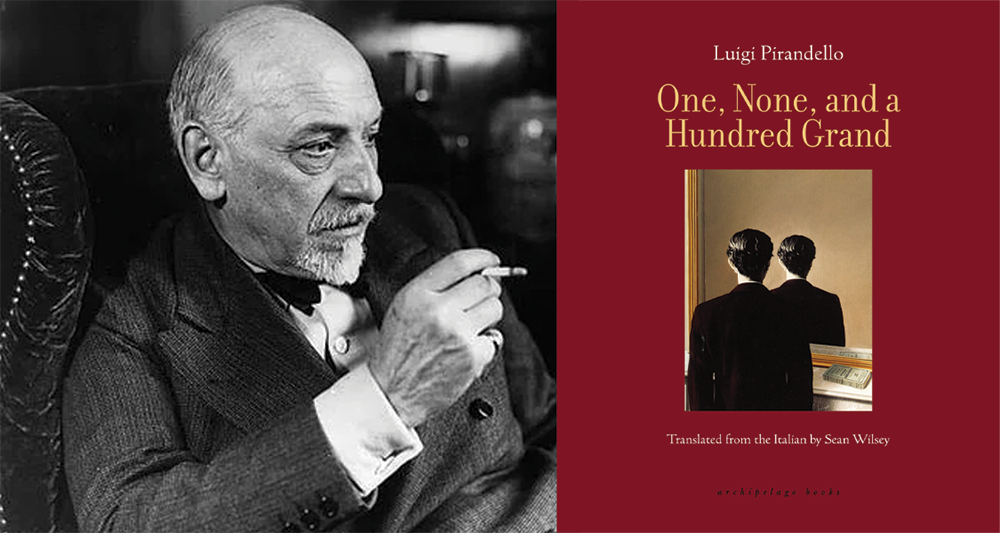

One, None, and a Hundred Grand by Luigi Pirandello, translated from the Italian by Sean Wilsey, Archipelago Books, 2025

Luigi Pirandello’s final novel, One, None, and a Hundred Grand, begins with a nose; the slight tilt of it, casually noted by a wife, sets off one of the most vertiginous descents into selfhood in all of literature. For Vitangelo Moscarda (meaning maggot, one of the many signifying names in this book), this offhand observation shatters a presumed unity: if his wife sees him differently from how he sees himself, who—or what—is he? What follows is a tragicomic unraveling of identity that, nearly a century later, reads with the vitality of a modern parable. In Sean Wilsey’s supple and stylish new translation, published by Archipelago Books, Pirandello’s masterpiece finds new life in an era that is just as fragmented as Moscarda’s mirror.

Though best known in the Anglophone world for his revolutionary plays—especially Six Characters in Search of an Author, which famously broke the fourth wall and dismantled the illusion of coherent identity onstage—Pirandello began his career as a philologist and prose writer, and this training in dialect and etymology shaped his understanding of identity as both an artifact of language and a performance of speech. In the theater, he would go on to stage this view with uncanny force: characters who refuse their scripts, actors who rebel against the author, spectators forced to confront their own role in meaning-making. But it is in One, None, and a Hundred Grand that Pirandello turns inward, eyeing the abundant fragments that compose each of us.

“Our personas are nothing but obsessions,” Moscarda reflects, echoing the novel’s central insight that identity is not essence, but fixation. The self we present to others is a patchwork of compulsive self-curations, performances, and masks; we are each one, none, and a hundred thousand—but those on the outside can only hold a single image of us, and so we come to believe in that image. It is tragic that we cannot see ourselves as we are, comic that we think a mirror could. The novel literalizes this condition, turning a bourgeois banker into a philosophical clown, a mystic, and eventually something close to a modern-day saint while dramatizing, in prose, the same theatrical destabilization that made Six Characters and Pirandello’s other plays so enduring. In its relentless self-dissection, One, None, and a Hundred Grand anticipates everything from Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical sociology to the algorithmic profiling of social media; it peers through the surface of the self and finds another level beneath, discovering surfaces all the way down.

This obsession with broken identity was not merely intellectual. Pirandello’s life—marked by financial collapse, domestic tragedy, and psychic instability—was samely a theater of selves. His marriage to a woman who suffered from paranoia and delusion isolated him emotionally, and his own persona, described by friends as elusive and protean, mirrored the instability of his characters. It’s no accident that his protagonists often speak in monologue to invisible others; Pirandello’s deepest dialogues were always with himself—or rather, with the hundred thousand selves he recognized within.

This philosophical vertigo also partly originates in the author’s native Sicily, which remains an island constructed from the dust of civilizations: Phoenician, Greek, Roman, Arab, Norman, Spanish. Palermo, where Pirandello studied, preserved something of its ethical and metaphysical inheritance from the Magna Graecia, with Socratic irony and Heraclitean flux persisting long after they had been elsewhere absorbed into Christian fixity. This Mediterranean multiplicity courses through the novel’s nerve. “For us,” Moscarda declares, “the world is the raw material of reconstruction.” In the ancient South, identity was always more porous, more negotiable, more theatrical. The hybrid city-states of Magna Graecia nurtured a view of the self not as interiority but as ethos: action, speech, manner, modulation, with the tragic chorus offering both a window onto the soul and a counterpoint to the very idea of individual depth—an echoing voice that displaced the singular. Pirandello, raised in that atmosphere and later, schooled by classical philology, inherited an ontology of masks and inverted it. If in Aeschylus the mask reveals fate, in One, None, and a Hundred Grand, fate is the mask, albeit one that is endlessly donned, cast off, remade.

Pirandello went on to Rome and eventually to Bonn, Germany, where he received his doctorate for a thesis on the dialect of his native Agrigento—and it’s telling that he had to go far north to study the syntax of home. Language, for him, was not a transparent medium but a crepuscular veil: a field of distortion and plurality. Just as Pirandello’s dramatic characters challenge the authors who create them, Moscarda breaks the narrative course to interrogate his own narrating self. This recursive, self-collapsing motion is the novel’s engine and, ultimately, its ethic. In a modernity obsessed with coherence, Pirandello insists on multiplicity.

And that multiplicity is more than psychological: it is historical, economic, and spiritual. The novel’s background is one of collapse and transformation. In 1903, a landslide flooded the sulfur mine that held Pirandello’s family fortune—both his father’s and his wife’s. The financial devastation was immediate. His wife Antonietta, already vulnerable, suffered a psychotic break, and never recovered. That personal unraveling—material and mental—echoes throughout One, None, and a Hundred Grand. Moscarda, heir to a provincial bank, becomes a deliberate saboteur of his own stability, dismantling his wealth, reputation, and identity piece by piece. This is not nihilism, but a pursuit of clarity through negation.

Stylistically, the umorismo that Pirandello is famous for—a blend of irony, pathos, and metaphysical queasiness—is everywhere in this novel. There is humor in Moscarda’s absurd attempts at self-erasure: his mirror exercises, his public fights, his attempts to provoke scandal just to dissolve the image others hold of him—but this humor is laced with something darker. To become “no one” is not a liberating escape into pure being; it is to pass through the void of recognition, to live without a stable role in the theater of the social. In this way, the novel does more than dramatize a personal crisis: it stages the ethical and aesthetic problem of being a visible subject. Moscarda does not deepen his self-understanding; he fragments it. He becomes a swarm. Late in the novel, he begins referring to himself in the plural. “We,” he writes, not out of imperial delusion or psychotic break, but because the singular no longer suffices. The self, once believed to be unified, is finally seen for what it is: a multitude of reflections projected by other people: the friend’s version, the wife’s version, the beggar’s version, the banker’s, the priest’s. Pirandello anticipates the insight that identity is never self-made, but always being molded by the eyes of others and the voices of place and speech.

But Pirandello is not merely a deconstructionist. He is, paradoxically, a moralist. By the end of the novel, Moscarda has rejected all worldly possessions, reputational attachments, and social roles. While he’s not Diogenes the Cynic living in a barrel in Athens, Moscarda is something analogous. He does not seek authenticity in performance, but finds peace through dissolution and refusal. In this, his journey converges with Pirandello’s late fascination with Franciscan mysticism—especially the idea of spogliamento, or radical divestment. Just as Saint Francis stripped naked in the public square to renounce his father’s wealth, Moscarda liquidates his bank, gives away his holdings, and vanishes into an asylum-like hospice on the margins of the city. He achieves, in Pirandellian terms, a negative sainthood—not by becoming something, but by ceasing to be anything.

Like Beckett’s Malone or Pessoa’s heteronyms, Moscarda discovers that perception itself is a trap: the self as seer occludes the seen. In the novel’s final gesture, he sits nameless and remote in the countryside, watching a donkey from afar as it moves and shakes itself—an ordinary creature in an indifferent landscape. It is not a resolution, but a surrender. A moment of grace, perhaps, in which the world no longer mirrors back a role. He watches but is not watched in return. He is no one—and finally, that is enough.

Sean Wilsey’s translation captures this tonal complexity with elegance and wit, rendering Moscarda’s manic internal monologues with a clarity that never flattens the prose’s metaphysical charge. Pirandello’s humor, ironic but never cruel, also comes through in full; the narrator is ridiculous and wise, egotistical and guileless, tragic and strangely blessed. Wilsey’s decision to translate the Italian title Uno, Nessuno e Centomila as One, None, and a Hundred Grand may raise eyebrows for its mildly arch tone, but it ultimately works; “grand” suggests not just number, but performance and money—identity as spectacle, overstatement, farce.

Six Characters in Search of an Author broke the fourth wall of the stage; One, None, and a Hundred Grand tears through the mirror of the self. It is a novel that reads eerily like prophecy in the age of avatars and curated profiles, deepfakes and self-surveillance—all of which already lay latent in Pirandello’s Palermo. What he gives us is a grammar for modern subjectivity—a way to name what it feels like to exist in the plural, without anchorage. In our present moment, when identity is increasingly and heinously weaponized and commodified, Pirandello’s refusal to grant the self any stable essence becomes not just unsettling but liberatory. We need not be what others make of us, nor do we need to obsessively “find ourselves” in the mirror of social legibility. We can choose, as Moscarda finally does, to unhook, renounce, reconstitute. We can, in other words, recognize the multitude within, and thereby glimpse—however briefly—what it means to be free.

Jordan Silversmith is the author of Redshift, Blueshift, winner of the 2020 Gival Press Novel Prize, and his poem “Praxis” received the 2020 Slippery Elm Prize in Poetry. He regularly writes on literature in translation.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: