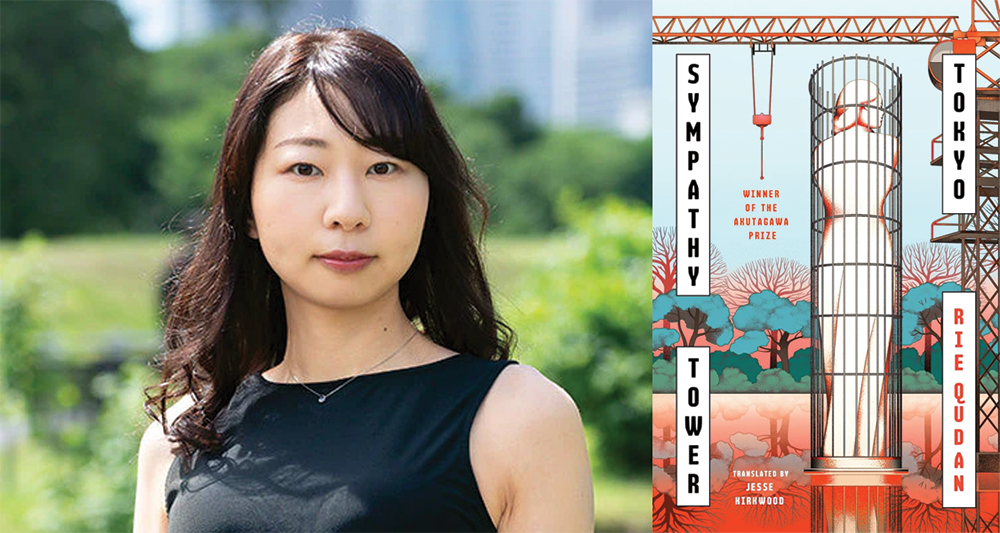

Sympathy Tower Tokyo by Rie Qudan, translated from the Japanese by Jesse Kirkwood, Penguin, 2025

Rie Qudan’s latest novel, Sympathy Tower Tokyo, garnered controversy in Japan when it won the prestigious Akutagawa Award in 2024. Questions immediately arose after the author announced that she used AI to help write parts of the story: around 5%, she specified. This led to the expected outrage regarding the dangers of AI in the arts, especially considering that the prize committee was unaware of its usage when they selected the novel. This is particularly interesting when at its center, Sympathy Tower Tokyo is a book about language—how words shape our thoughts and build our dreams—but it is also about the social consequences when language begins to lose its meaning.

Set in the near future, the novel’s igniting incident is a gigantic new prison being constructed in the heart of Tokyo. The commission for the building’s design has gone to celebrity architect Sara Machina, who wants to create a big beautiful tower, one that will stand in conversation with Zaha Hadid’s National Stadium. In this alternative Japan, Hadid’s stadium was built in time for the 2020 Olympics, which took place as originally scheduled (contrary to its delay due to COVID). The new prison, the titular “Sympathy Tower,” is intended to be a place of rehabilitation for those labeled Homo miserabilis, or “humans deserving sympathy.” It is thus meant to convey the idea that incarcerated prisoners are themselves victims of systemic economic and social injustice—including murderers and rapists.

This tower will be the crowning achievement of Sara’s career, but she is filled with doubt. First, might this kind of sympathy lead to a lack of criminal accountability? Sara is herself a victim of sexual assault, and she believes that she has never gotten justice for what happened to her because she lacked the language to adequately explain the experience. In her case, she was blamed when it was discovered that the rapist was her boyfriend—someone she loved and invited into her home. For Sara, that violence of that fact was beyond conveyance.

In addition to this, she is also worried about the relationship between the sanitization of language and the execution of actual change. For example, how will simply renaming the prison “Sympathy Tower” address economic inequality, believed to be one of the root causes of urban crime? In Japan, it is common for companies, cities, and even train stations to change their names, often for reasons related to branding or to renew public image in the aftermath of scandal. In bringing this practice to the forefront, Qudan goes beyond interrogating wokeness and how we use language to ameliorate social ills, asking if, in addition to policing words, we have done anything concrete to solve pervasive problems? For example, in changing the word for criminal from 犯罪者 hanzai-sha—which literally means someone who commits a moral crime—to ホモミゼラビリス Homo miserabilis, has any real resolution taken place?

It is in his skillful tackling of such linguistic issues that Jesse Kirkwood’s English translation really shines. Japanese has three different scripts, all of them being used in various combinations to communicate. In addition to Chinese characters (kanji), Japanese is also written using the phonetic systems hiragana and katakana. The famous landmark Tokyo Tower, for example, is written using a combination of kanji for the word Tokyo and katakana to render the English word tower into Japanese. In Sympathy Tower Tokyo, Sara had originally expected to name her tower in a combination of kanji and katakana, or even in all kanji as 東京都同情塔 Tōkyō-to Dōjō-tō—which has a natural rhyme. She is later disappointed when she is informed that the stakeholders have decided to render the name entirely in katakana asシンパシータワートーキョー. In Japanese, the medium of written script is part of the message, and Kirkwood, in his translator’s note about the use of katakana at the start of the book, explains the situation as such:

These days, their use is often associated with buzzwords, sales jargon, pop culture, and a general desire to make things seem cool, modern, exciting, new. As our protagonist, Sara, notes, katakana-based words combine versatility and vagueness in a way that makes them an attractive choice for anyone wanting to avoid a firm commitment to meaning.

This quandary regarding vagueness and katakana’s neutralizing function has a long history in Japan. After the nation’s defeat in World War II, the famous novelist Naoya Shiga proposed that the Japanese language be abolished, suggesting instead that the country adopt French—“the most beautiful language in the world.” This created a national uproar, especially given Shiga’s prominent stature, and also fed into the contemporaneous suspicion that Japan’s exceedingly difficult language could be holding them back in terms of development. From this time onward, however, loanwords from English and other European languages—all rendered in katakana—have been used extensively, a custom that has only escalated with the rise of social media and AI.

Qudan, in an interview with The Guardian, said that her novel was written in part against the backdrop of prime minister Shinzo Abe’s assassination in 2022. Like many, she was astonished by the level of sympathy that the assailant received, despite the outrageousness of the crime. This was due to the childhood trauma the assailant experienced after his mother joined the controversial Unification Church; she impoverished the family through her unsustainable donations, and, according to the assailant, severely neglected her children. Some people felt that he was the victim of a cult, in addition to having suffered the overwhelming economic malaise and social turmoil that many people his age felt in contemporary Japan. This led to a surprising public demand for leniency, despite the fact that he murdered a former prime minister in a public place, using a handmade handgun.

Qudan also based Sympathy Tower Tokyo on Norway’s famously luxurious—and humane—Halden Prison, which has been cited as having contributed to Norway’s extremely low recidivism rates, among the world’s lowest. Like Halden, the Sympathy Tower of the novel is constructed in a way that views the incarcerated as sympathetic subjects by housing them in relative comfort, overlooking a park and focusing on rehabilitation. Indeed, the place is so pleasant that many of the incarcerated choose to remain after their sentences have been served. Despite their imprisonment, some feel that perhaps they are better off inside, and this is the conclusion reached by one of the other main characters in the novel, Sara’s much younger boyfriend, Takt. The son of a single mother, Takt was raised in abject poverty and watched as his mother being led into a life of petty crime, eventually ending up in Sympathy Tower alongside her son.

The relative solace of such imprisonment seems like a positive—and yet such captivity still affects the body, mind, and ultimately social relationships. In Sympathy Tower, all language is regulated, and only pleasing words are permitted to be spoken. Policing has become internalized, with people burdened by something Sara describes as her “brain censor.” She cannot escape the feeling that the changes to language—led by both AI and progressivism—are ultimately harmful to culture and society.

In the novel we see the ways in which AI, like social media before it, neutralizes and algorithmicizes language, rendering it less precise and more ambiguous, thus decreasing meaning and social connection by diluting the power to communicate with nuance and sincerity. AI language models are programmed to give the most “average” or “likely” response to a prompt, erasing individuality, novelty, and ultimately any potential of true empathy. As Qudan writes:

It would be Babel all over again. Sympathy Tower Tokyo would throw our language into disarray; it would tear the world apart. Not because, dizzy with our architectural prowess, we had reached too close to heaven and enraged the gods, but because we had begun to abuse language, to bend and stretch and break it as we each saw fit, so that before long no one could understand what anyone else was saying. The moment words left our mouths they would become to our listener a baffling tirade. A world ravaged by ranting. The era of the endless monologue.

In an interview with NHK about writing this novel—and specifically about her controversial use of ChatGPT to help with the AI dialogue—Qudan explained that her original motivation was the discomfort she felt in seeing how social media and AI were enabling the distortion and carelessness of language in Japan, causing divisions and issues in critical thinking. As such, both the narrative and the process of Sympathy Tower Tokyo aims to illustrate the harm of offloading meaning to algorithmic methods. In Kirkwood’s brilliant translation of not only Qudan’s original prose but also cultural and linguistic particularities, even readers who have little experience with Japanese will be fully engaged in its politics—as distinct as they are global—when reading this extraordinary novel.

Leanne Ogasawara lived in Japan, where she worked as a translator for two decades. Her reviews have appeared in the Chicago Review of Books, Lit Hub, The Millions, Harvard Review, The Rumpus, the New Rambler (translated into Chinese for Rujiawang), and elsewhere. She currently serves as the translation editor of the Kyoto Journal.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: