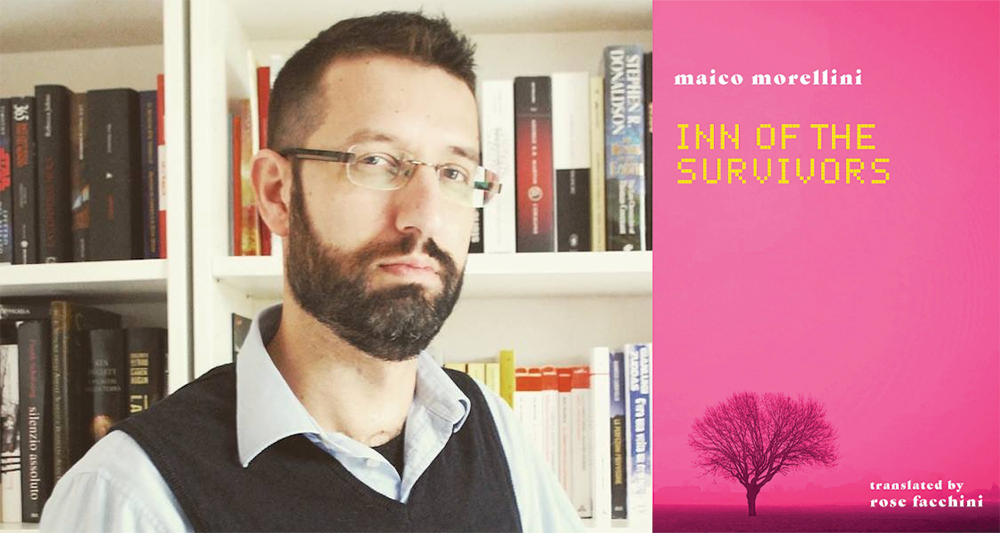

Inn of the Survivors by Maico Morellini, translated from the Italian by Rose Facchini, Snuggly Books, 2025

Inn of the Survivors is Italian writer Maico Morellini’s debut in the English language, a haunting and eerily familiar work from a sophisticated voice in speculative fiction, arriving in Rose Facchini’s translation. Set in a dystopian future after an unspecified climate disaster, the novella tells the story of a seventeen-year-old girl’s arrival at the titular Inn of the Survivors, a haven on the Adriatic coast. Having taken off from her remote home in the mountains overlooking the Po River Valley, and following a three-year trek through Bologna, Forlì, and Cesena, she finally reaches the Inn and encounters others like her: people who have been on the run, trying to survive, living with trauma, grief, or shame. The price of staying? You must tell your story.

Lest you think my use of the second person is casual, it should be said that except for the backstory—which appears in the latter half—the novella is written entirely in the second person. While this narrative device appears often enough in English, it is far less common in Italian, with only two novels coming easily to mind: Se una notte d’inverno un viaggiatore by Italo Calvino, and the most recent Strega Prize winner Come d’aria by Ada d’Adamo. This is likely due to the Italian third person impersonal (si + verb), which can mean anything from “you,” to the more formal-sounding “one,” to the most passive of voices. As such, choosing to write this tale in the second person was a bold and effective choice on the part of the author, with the new text sounding entirely natural (the ideal result for a work of cli-fi). Yet, thanks to specific geographic locations that are an integral part of the story and the protagonist’s desire to understand her country, it still retains a quality we can call “Italian.”

From the opening lines, the mood is tangible and the writing flows smoothly. We’re drawn into the surroundings, absorbing aspects of the girl and the harsh setting, acquiring subtle but powerful clues about the state of the world:

The last few kilometers, the ones that change the atmosphere of the forest and transform it into a swamp, are the most difficult to cross. The deep verdure of the trees and the dense shadows of the undergrowth turn branches and rocks into slippery traps.

You trip, one, two, three times.

‘Christ.’ Your sputtered curse mixes with the rain, the drops engorged by their journey through the leaves and branches, falling to the ground like bombs. You are only seventeen, but you have learned to hide it. You have learned to act older. If someone were to look you in the eye, they might discover your true age, but nobody does. You do not want them to.

The second person narration lends a game-like quality to the way we advance through the forest in the first two chapters—as if we’re also involved in the action, able to make choices, to help the narrator/avatar make her way towards her destination, towards the desired outcome. But this isn’t simply the work of perspective; Facchini’s nimble and elegant translation is an additional boon. I noticed repeatedly that her phrasing never sounds artificial and imparts just the right mood, but this is especially notable in an ethereal passage describing the sky. Here is the line in the original, followed by her translation:

. . . intravedi le nubi. Un vortice costante, nero con striature sottili, bianche, nembi gelidi che si incrociano tra loro. E poi lampi e tuoni lontani che non appartengono a quel temporale.

. . . you catch a glimpse of the overcast skies. A roiling swirl, black with thin, white striations, icy storm clouds that collide with one another. And then distant thunder and lightning that play no part in this storm.

Notice how Facchini adopts the idiomatic expression “play no part” to separate the distant thunder and lightning from the strange, swirling atmospheric blitz unfolding above the narrator’s head; in the original, Morellini uses “non appartengono,” which literally means that the distant electrical phenomena do not belong to the events in the sky. The translator’s choice also relays the tough determination of the character and her ability to focus on putting one foot in front of the other, while tapping into the role-playing vibe already described.

Still, there’s something paradoxical about second-person narration; it draws us in while also holding us at arm’s length. We, the reader, hover like rainclouds above the water’s surface—present, but a different element, unintegrated. For much of the novella, we long to know more about the narrator, but Morellini first exposes us to her state of mind—an emotional terrain shaped by something that resembles grief. Only when she looks at the woods around her, literally unable to see the forest for the trees, are we catapulted with her back into her memories:

Mom always insisted that you and your siblings learn the names of the trees by heart. It was one of those little things she truly cared about, one of those little rules that she enforced no matter what. . .

Recalling that name pains you because it belongs to a past that will never return, and that kind of past, when it is lost forever, can really hurt.

Soon the novella becomes less of a game and more a litany of sorrow, and we come to understand that the story is shaped by endless degrees of hurt, countless declensions of pain. Unanswered questions, unhealed wounds, secrets, and a sense of shame bleed through the pages, showing us a character who has suffered, informing us through a physicality that’s hard to ignore:

You pass your gloved hand over the root of your braid, then climb up to the base of your head: your wounds are hidden, but they are there. Under your hair. In your mind.

We learn, viscerally, that she is fleeing a new world order—where schools and governments divide people into camps: the “flawed” and the “pure.” She wants no part in it and has to get away, but self-distancing, she admits, “is an exile that took away more than you ever had.”

Stability and instability. Throughout Inn of the Survivors, the theme of balance comes up time and again—literally and metaphorically. To follow her story, we must stay nimble, alert, flexible. Morellini takes care with physicality, monitoring her journey step by step: “You bend your knees, find your footing, push, muscles stretch and release the accumulated energy, a leap, then another.” This keen reflection on the physical experience carries through to the awareness of setting: “You cross the parking lot and walking on the asphalt makes you feel strange. . . After all those months spent mostly on the soft and unstable ground of the forest, finding such sturdy support almost makes you lose your balance.” Through all this, the question of knowledge lingers beneath: How do we know what we know? The knowledge of the body is undeniable, but Morellini contrasts it with the kind of knowing that is forced upon us—learned through schooling or the family:

. . . when you were little, your father brought you to a slaughterhouse because it was important for you and your siblings to know death as early as possible. You know it in an intimate way. . . . The animals had no real idea what would happen to them shortly thereafter, yet they knew. Silent stares, Knowing stares, loaded with a painful awareness that forced you to lower your gaze. They knew, but the pain you saw was not fear. It was comprehension. They seemed to watch you with pity.

The first kind of knowledge is visceral, while the second is shaped by how others see us. In being drawn into the narrative through second-person, we’re both implicated and distanced by the character’s knowledge. Do we see ourselves in the girl? Are we owning our role in climate collapse? What side of the mirror are we on? How do we, as readers, engage with the text? For speculative fiction does not simply ask what the world might one day become, but gets us wondering about what role we currently have in shaping it. This tale lets us straddle both.

At the end of the second chapter, the girl arrives at the Inn: “an odd tangle” of boats, gangplanks, girders, tie-rods, powered by generators that aren’t like the ones back on the farm, which “coughed like asthmatic swine and blew more hot air than your geography teacher.” Instead, these machines are new—a fact that surprises her: “Who knows why, but you had convinced yourself that the Inn is a place out of time and without technology; looking around, you discover that is not the case.” Yet despite the promising nature of the place, everything else remains disconcerting: the environment, the air, light, and mood. “A dense mist has remained from the rain, an opaque film the color of milk that swallowed the twilight, transforming the landscape into a place out of time.”

In the third chapter, Morellini adopts the “normal” mode of first-person narration to have our protagonist tell her story—though there’s hardly anything “normal” about it. The novella then comes to a conclusion with a brief fourth chapter after she has finished speaking, transporting us back to the Inn and inciting another reflection on the idea of knowledge: how it is exchanged, how it changes us.

You do not see the mute comprehension of an animal in the slaughterhouse. Now you see something different. You see your own eyes, the expression you wore when you wove between the caged cows, with dad. Knowing eyes that have witnessed something.

The narrator realizes that the Inn is filled with people who, like herself, “have lost the game of life. Yet, somehow, they continue to play.” And we’re there, too. Morellini and Facchini have graciously welcomed us into this game-world, memory-palace, eco-fable. We’ve been pulled into the tale much like Coleridge’s wedding guest, who “cannot choose but hear” as the Mariner tells his forlorn tale. In our hearing, we have been led to reflect on how life is like a game, how friendship can sustain us, and how sharing our stories can save us from even the bleakest of circumstances.

Oonagh Stransky is a translator of Italian literature. Her most recent publications include works by Domenico Starnone, Eugenio Montale, and Erminia Dell’Oro. She is currently based in Turin, Italy.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: