The fall of the Berlin Wall catalysed a monumental case of political integration in the West, heralding a necessary conciliation of disparate politics, economics, psychologies, values, and socialities. Of this time, the grand dialogues and negotiations between international governmental bodies are well-documented and enshrined in textbooks, but the stories of ordinary lives swept up in this extraordinary fusion are still in the middle of being told, processed, and understood. One of the most subtle—yet enduring—issues is the distinct views of sexuality and intimacy in the two Germanies, which reflects the greater ideological differences in both unpredictable and surprising ways. In the following essay, Moumita Ghosh takes a look at two contemporary novels that feature romantic relationships under the political influence, Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairos and Ralf Rothmann’s Fire Doesn’t Burn, illustrating how the quakes of national movements send their aftershocks into our most private spheres.

Still, there is one thing they still do that hasn’t changed: when they leave a place together, he holds out her coat, she slips into it frontwise, briefly holds him in her arms, then slips it off and puts it on the right way around. But probably, even these habits, in which they took pleasure and pride, and which confirmed their intimacy, are nothing more than a hollow-bellied Trojan horse.

—Jenny Erpenbeck, Kairos

Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairos, winner of the International Booker Prize in 2024, sketches a tumultuous romance between Katharina, a young woman, and Hans, a married man thirty-four years her senior. Translated by Michael Hofmann and set in 80s Germany, the text intertwines the couple’s intimate narrative with national history. Hans, his childhood overcast by the Hitler Youth and his father’s Nazi sympathies, is eventually revealed to be a Stasi informant, having ‘decided in favour of that part of Germany that had Anti-Fascism written on its red banners.’ Katharina, in contrast, was born after the war and is characterised by a certain political apathy despite her youth; rather, she comes across as a citizen of the imminent reunification. When she travels to the West for an internship in Frankfurt and gets romantically involved with a colleague, this fluidity of her character becomes even more apparent. As her interactions with Vadim, her colleague, progresses slowly and spontaneously, her relationship with Hans becomes even more stifling and unnatural—and what comes across as the modern sexual mores of East Germany soon reveal themselves to have sinister tones. Intimacies begin to mirror political realities as Hans becomes more controlling with Katharina—a danger that has subtly existed since the beginning of their acquaintance. Eventually, their relationship becomes a surrogate of East Germany, where sexual liberation sat uncomfortably with repressive surveillance, while their devolving affinity also collaterally communicates the decaying of the present and the transition towards reunification.

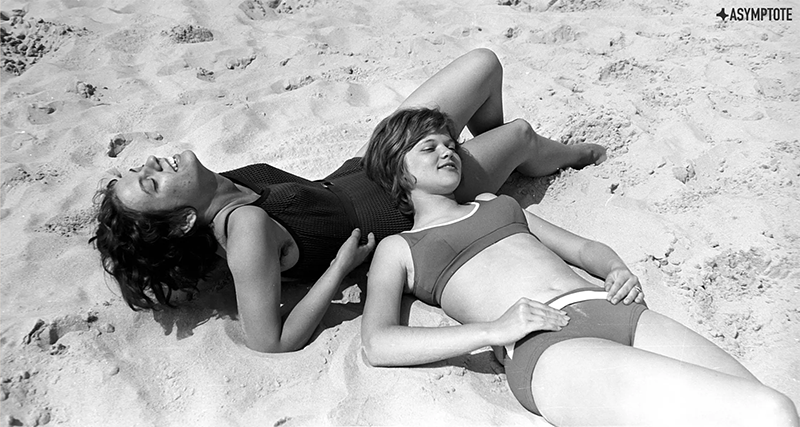

Reunification came in 1989, and before its eventual fall, sexual attitudes on both sides of the wall differed significantly; East German attitudes under the communist regime evolved to be more relaxed, with public nudism being a hallmark of East Germanness, while in the West, church-based restrictions regulated sexual behaviours. The sixties especially unfolded as an important decade, with debates around sex taking dominance; the introduction of the birth control pill during this time was a momentous occasion, since it placed male and female sexual experiences on an equal plane. Moral standards around women’s pleasure—both within and prior to marriage—were beginning to be reimagined, heralding the arrival of a new sexual order.

In the otherwise conservative West, this moment saw a concurrent expansion of the erotic industry in the wake of the ‘economic miracle.’ Dubbed as a sex wave, sexual consumption moved from discreet shipments in brown paper wrappers to sex shops. This wave was initially posed as an extension of conjugal life, but legal revisions to the sexual-criminal code soon transformed it into a porn wave, focusing on solo male pleasure. Meanwhile, in the East and its relatively evolved sexual mores, the introduction of the birth control pill was followed by the legalisation of abortion. Such freedoms served as a distraction from the burdens of living under an otherwise authoritarian state, which effectively used intimacy and fraudulent relationships for purposes of surveillance. Yet the East never had a public, commercialised sexual culture—at least, not till the reunification years.

In fact, after reunification, nudist culture became an issue of contention. West German attempts to demarcate nudist and non-nudist areas on Baltic Sea beaches was seen as a sign of colonisation, since nudism was a sign of sexual liberalism for East Germans, imbibed with meanings deeper than eroticism. Met with sexual consumerism, however, women living in former East Germany also experienced discomfort with their nudism in the presence of what sexologist Kurt Stake called a ‘pornographically schooled gaze’ in the West. Furthermore, West German porn and erotic goods did not do well with the former Easterners as the initial rush of excitement soon turned into rejection. However, as Josie McLellan writes in Love in the Time of Communism, East Germany did see a proliferation of public erotic culture in the last fifteen years of its existence—one that was emblematic of heterosexual male desire. This was not simply due to extraneous influences like smuggled erotica from West Germany, but originated from the country’s own culture (albeit one that was deeply influenced by the West). For example, nude photography, which tried to portray an asexual aesthetic in a country that condemned the commercialisation of sex, eventually came to be spectacularly focused on the naked female body, and heavily emulated Western visual discourses. Even state-run publishing houses produced glossy books of nude photographs for export purposes as erotica came to serve an important economic function. But despite these contradictions, there existed an idea of a certain socialist morality which—although not unsullied by the consumerism of their Western neighbour—labelled itself as more evolved in the realm of intimacy.

In Kairos, Katharina walks into a sex shop when she visits West Germany, and it gives her a feeling of crossing a frontier—exactly how she felt when the train carrying her from the East had entered the West a week earlier. Overwhelmed by the pornographic materials, she is excited yet nauseous at the excess of male desire, but when Hans presents her erotic pictures imbibed with dynamics of control and hierarchy, she looks at them earnestly: ‘The obscene enters in at her eyes and goes deep into her mind. And from there it can find no escape. His pleasure would not be half as intense if Katharina’s face did not look so pure.’ Katharina is unaware that this moment will come to seem as an inauguration of the abusive ordeal Hans will drag her through.

Katharina’s internship in Frankfurt also leads to an individual conflict between her life in the West and the life she occasionally slips back into when she meets Hans—a life that feels like it no longer belongs to her. When she finds a riding crop that resembles one in the erotic pictures given to her by Hans, she takes it to him: ‘Potency in a plastic bag . . . Is she buying her freedom in this way?’ Then, three weeks after reunification, Katharina stands in front of a Berlin sex shop where Hans had occasionally picked up erotic magazines for her: ‘This other Hans, who seems perfectly at home in the West, she now sees for the first time.’ Despite his decision to migrate to the East due to his socialist beliefs, Hans seems to have erotic tendencies in concurrence with the sexual temperament so often associated with the West. Interestingly, those tendencies come together with his disposition to torment Katharina in ways strangely evocative of his Stasi past, such as interrogating Katharina about her time in Frankfurt over a series of audio cassette exchanges:

Before he leaves, Hans promises her that he’ll have the fifth cassette ready by the end of the week.

But for that he first needs her answers to the fourth.

Katharina’s murky sense of self— a souvenir of the precarious intimacy she shares with Hans— also assumes that she deserves such treatment. As Erpenbeck writes:

Yes, she wants him to hit her.

Wants it purely out of the desire that it does her in.

A long time ago it was a game. Now it’s deadly earnest. Now the reality has touched her. . .

Not until he realizes she’s been crying for a long time under his blows does he stop and puts the belt away…

Offering a different perspective of erotic intimacies amidst reunification is Ralf Rothman’s Fire Doesn’t Burn (translated by Mike Mitchell), which unfolds in the early 2000s—almost twenty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Rothman shapes erotic sentiments with the same as logic as Erpenbeck, ascribing sexual temperaments to the East and the West, but in contrast to Erpenbeck’s nuanced treatment, Rothman frames such temperaments in extremes. In the novel, Alina and Wolf are a couple with a significant age gap, relocating to the eastern edge of Berlin to seek a respite from their prosaic lives. There, glimpses into a once-existing East and interactions with former citizens of the GDR are common. While Alina is blissfully consumed in setting up their shared countryside apartment, however, Wolf feels confined by the sudden domestic arrangement—an arrangement that becomes even more familial when Alina brings her colleague’s dog home. Eventually, monotony lures Wolf into an affair with Charlotte, a former acquaintance.

Even though Alina is seldom guilty about her sexual desires, Wolf cannot imagine indulging, with her, in the kind of sexual acts he performs with Charlotte—who, similar to himself, represents a sexually repressive Catholic upbringing that succumbs to the insatiable plastic impulses of the erotic industry. As Rothman describes: ‘For Alina . . . sex is as natural as breathing or drinking water . . . Wolf’s driving force, on the other hand, comes from the taboo which gives it a certain vehemence . . . .’

Wolf associates his perversions with having grown up prior to an era of evolving sexual attitudes, and sees himself as incongruous with Alina’s erotic personality—since she belongs to a generation born after the sexual revolution. Moreover, Wolf anticipates that his life with Alina in the eastern edge of Berlin might eventually resemble that of their neighbours from across the road—monotonous and lacking any erotic element. ‘Greylings’, he secretly christens the other couple, commenting that ‘the two seem to live out their lives together in relative silence, never laugh or smile, never embrace or even touch one another, to say nothing of kissing, and usually wear shapeless, nondescript clothes.’ He continually associates the East with the colour grey, judging that the former citizens of the GDR act in a certain withdrawn manner, a ‘delayed friendliness’ that he reads as a consequence of having previously lived in a surveillance state.

Situating the erstwhile East on a spectrum of greyness is not new. In Remembering and Rethinking the GDR, Chloe Pavar describes a piece of paper exhibited at the DDR Museum-Malchow, which iterates: ‘People escaped from the grey monotony of “real existing socialism” by plunging into the torrent of capitalist colour.’ Such insistence on a lack of colour also represents a Western lens of highlighting an economy marked by scarcity, since such lack can also be read as a lack of variety. This is interesting when read against Charlotte, who claims that without the ‘variety’ of sexual activity she offered to Wolf, he would have lost all desire for Alina—who would then be vegetating in front of the television like all the other former citizens of the GDR.

Wolf finally confesses his transgression to Alina on a trip commemorating his fiftieth birthday, and as she disappears only to reappear again, by chance, at a train station in the evening, Wolf thinks:

. . . he can read in the gentle seriousness of her gaze and the calm composure of her expression that she would hardly be surprised if, on the day after he’d died, he continued to live with her quite normally, giving her breakfast in bed, buttering her toast, pouring her coffee. Seen in the light of her love, it can be no other way . . .

Thus, Alina eventually accommodates the idea of nonexclusive intimacy, but also settles into a deep state of melancholia. Later, she is diagnosed with a terminal illness and commits suicide.

As Katie Sutton documents in Sexuality in Modern German History, the event of reunification was frequently portrayed in German media through the motif of marriage and, more importantly, of heterosexual desire—with the East referred to the conquered, feminised half. It is rather impossible not to read Wolf’s inconsideration and Alina’s unrestrained love as the West’s colonisation of a country which no longer exists, which only appears in memories. On the other hand, as Josie McLellan points out, former East Germans often indulged in sexual nostalgia post-reunification as a way to reclaim the authenticity of their past lives and to critique the consumerism of the West; even those who were highly critical of the regime experienced tender moments of erotic desire and freedom.

Ultimately, both Katharina’s and Alina’s narrative of intimacy unfold as erotic, emotional, and spatial allegories of their distinct political realities—whether that be of the impossible coupling of sexual liberation with the looming threat of the Stasi’s salacious surveillance or in the latter case, the perversions of capitalism.

Moumita Ghosh is a Kolkata-based freelance writer and researcher.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: