Throughout his life and literary career, Henrik Pontoppidan held an unflinching eye on the culture and time that surrounded him, pinning down what he saw as its most spectacular failures in characteristically incisive, comic, and penetrating fictions. This ability to portrait society earned him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1917, and today, he continues to be hailed by some as ‘Denmark’s greatest realist’. A recently published compilation of his two novellas, gathered under the title The White Bear, was our Book Club selection for the month of June, and in it one finds Pontoppidan at his most reflective and honest, telling the stories of hypocritical morality and doomed love. In this following interview, we speak with translator Paul Larkin about his discovery of this under-celebrated author, Pontoppidan’s relevance in our current political climate, and what individualism means in these works.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Xiao Yue Shan (XYS): Despite being a Nobel laureate, Henrik Pontoppidan has a relatively low profile in the Anglosphere; could you tell us a bit about how you came to discover his work, and what drew you into translating it?

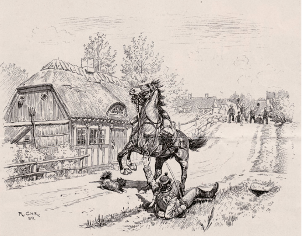

Paul Larkin (PL): It is actually a deeply interesting question. I first came across Pontoppidan’s works whilst still a young man, working as a deck-boy in the Danish merchant navy. This navy has a very well organised library service, which did not just furnish books to ships but also films and—if I recall properly—audio material, which was mainly in cassette format back then. And this material was by no means all of the ‘tabloid’ variety. Much of it was serious literature, serious celluloid stuff on a 16mm format. By about a year and a half into my service, I had enough Danish to comprehend good writers like Pontoppidan, and the first short story I read was ‘Den første Gendarm’ (The First Gendarme)—see illustration. This had me laughing out loud, as Pontoppidan sends up the timid villagers seeking to somehow get the better of the lone, armed gendarme during a tense period in modern Danish history when the state sought to impose draconian laws. Eventually a barking dog does the job for them. The villagers then concocted their own legends . . .

By the time I got to University, I realised, of course, that there was a lot more to Pontoppidan’s bow than the short story format, social realist tales, and caustic fables. However, it was not until I read the magnificent A Fortunate Man that I resolved to translate Pontoppidan. I am still amazed at how little of his work has made its way into English.

XYS: Those who read Pontoppidan in the original Danish have commented on the author’s sensitivity to the ‘plasticity’ of language, and one can sense this in your translation as well with beautiful moments like a fountain’s ‘endless leaden murmuring,’ or in impassioned bursts of dialogue like ‘Love-refrains. Love-laments. Love-waffle. . .’. Were there particular stylistic choices that you made in this translation process, or any internal pivots you had to make in order to inhabit this author’s language?

PL: I really don’t think writing style, or styles—these dictate your choice of words to some extent—can be taught. It’s a controversial view, I know, but the best thing authors can do is to read a massive amount of good books and serious literature in all kinds of genres, thereby building up their word banks and fluency with words. An overall awareness of different forms and idioms helps also.

Crucially, an ear for the tonality and rhythm of words is accrued over time by the simple fact of reading and re-reading. Armed with this, when the artist/translator encounters the plasticity you speak of, and Pontoppidan’s joy in this—his relish in savouring words and phrases and moulding them into an overall form—we embrace this spirit, and the Muse conveys your words to the page, I find. Or She does so when you are at your best, at least. Where I do enact a pivot, as it were, is by consciously listening for vernacular speech, as this is one of Pontoppidan’s great strengths, and of Danish literature generally. Ordinary language returned to myth. It is one of my great strengths, too. Writers and translators are very often too posh.

XYS: In the titular novella of The White Bear, Pontoppidan shows a great attachment for the Danish colony of Greenland, and the passages describing that mercurial landscape are amongst some of the most romantic in this text. Here, he adulates the wild and excoriates the ‘civilised,’ but does so more through the subtleties of language and diction. As translator, did you notice any such instances of switching between linguistic modes to communicate certain ideas or evocations?

PL: Pontoppidan was fascinated with Greenland and tended to romanticise and worship vast, wild, remote places. They are mirrors, or substitutes perhaps, for his vast inner life and its constant tumult. His inner Greenland, if you like. In 1876, he actually applied for a position as a ‘student assistant’ with a research expedition going to the arctic circle in order to study Greenland’s inland ice region. This was led by Gustav Holm. He apparently made it to the last round and was bitterly disappointed not to make the cut.

I suppose my point here, to answer the question, is that I follow Pontoppidan’s lead in switching between lyrical passages that often literally sweep us off our feet in their breadth and majesty, and then very specific flora and fauna ‘reports’ that could come from an expedition log. Steinbeck’s ‘The Log from the Sea of Cortez’ comes to mind. One other aspect, though, is the respect he shows for Inuit culture. This was rare back then. Anti-Greenlander racism in Denmark is not just a recent thing, and Pontoppidan challenges that with this novella, which is much more nuanced than even the Danes understand.

XYS: Individualism was still emerging and taking shape while Pontoppidan was alive, and now, we’re beginning to see some of its more sinister, catastrophic incarnations and consequences. The novellas here especially demonstrate their author’s commitment to personal and psychic resolve against the inundation of societal norms, and it is interesting to read them at a time when social bonds and divides are growingly strained. I wonder if you see similar echoes between Pontoppidan’s time and our own, and what it may mean to read him today?

PL: I think that modernism, for which Pontoppidan was an early frontrunner, was a protest—both against mass media conformity and its fake portrayal of individualism. Or its exalting of a false individualism. By the time we get to Joyce and Proust, authors felt the need to create new myths that would disrupt that deadening and fake process, as well as its attendant empty language. Their predictions and warnings about blind conformity have proven to be true; the individualism promoted by Silicon Valley positivists and their techno feudalist gurus is a sham. Their language might invoke the rights of the individual, but their favourite words and phrases are relentlessness, aggression, seizing hold of history. They even invoke Nietzsche, who would be appalled at their supremacism. There is a lesson from both novellas against all this. In ‘The White Bear,’ Thorkild Müller’s tragedy was that—faced with a cynical establishment—he did not know how to protect his sacred, empathetic idealism and to use it for the common good. The moment when he bans tithes is the moment of his defeat, because he goes beyond the culture and understanding of the folk he wishes to nurture. Jørgen Hallager’s individualism in ‘The Rearguard,’ on the other hand, is too rigid and arrogant. Pontoppidan’s unspoken philosophy is that we must always seek to bring the people with us, by good example and a principled but flexible stance.

XYS: ‘The White Bear’ ends with a powerful line: ‘You get the tyrants you deserve.’ I’m curious to hear your thoughts on this conclusion—what it indicates about Pontoppidan’s point of view as a writer, and what you think about this dark, final condemnation.

PL: Pontoppidan was influenced by both Nietzsche and Kierkegaard—two philosophers who stressed individual dignity and the idea that every human being, without exception, has a life task. We seek to have a life view. This places a great responsibility on each individual to step up, as the saying goes these days, but as we know, people often understandably shrink back from that burden, and this is the space that the tyrant steps into. We human beings allow this to happen by way of our torpor, cowardice, or downright intolerance. This was Pontoppidan’s view. The only safeguard against tyranny is democratic (and spiritual/intellectual) courage. If we fail in that—well. . . you get what you deserve! Pontoppidan was a closet Socrates of his day.

XYS: Through both of these novellas veer towards the cynical, ‘The Rearguard’ is especially tragic, with Pontoppidan thoroughly expressing his vision of love definitively not conquering all, as well as building this somewhat deflating concept that our ideals and principles only constitute a minor part of ourselves—that we are always giving in to hypocrisy and self-delusion. In light of his work being called a mirror of Danish society, what were the particular sociocultural or historical elements of his milieu that led to the development of such vicious criticisms?

PL: We have to remember that Pontoppidan’s withering gaze was firmly directed at Danish society. His view was that Danes and their society had accepted a kind of bland mediocrity, and that the people in Denmark who tried to break that mould were often fanatics (Hallager) or dreamers (Ursula), who were unable to get anything done. Compare this with the magnificent Jakobe Salomon in A Fortunate Man, who does indeed get things done, despite the collapse of her relationship with Per. Jakobe, of course, is portrayed as a ‘European,’ not a Dane.

I think what Pontoppidan intuits is that after Denmark’s defeat by Germany in the Schleswig-Holstein war of 1864, Denmark collapsed economically to some extent—and intellectually to a large extent. The First World War darkened Pontoppidan’s vision even further. Denmark only got its respect back with the successful and extremely brave resistance movement in the Second World War, but Pontoppidan was too old to fully appreciate and celebrate that. He died in the middle of that war.

XYS: One thing that I found interesting while reading about Pontoppidan is that he was deeply disillusioned with the rise of capitalism and its destructions, but could not relate to socialism due to his own bourgeois background—and thus he leaned towards spiritualism and asceticism in lieu of solidarity. This sense of being in-between dominant movements feels deeply resonant with the contemporary political landscape’s bipolarity, and I wonder if in his work, readers can find some guidance as to how to navigate a sense of political non-belonging.

PL: Pontoppidan’s political sensibilities were essentially social democratic, but they had a healthy seam of anarchism running through them—anarchism in the old traditional sense: distrust of an overbearing state and the dignity of the individual. In terms of ascetism and spiritualism, Pontoppidan never renounced his formal affinity with the Christian church. I am tempted to compare his lifeview with the sobornost philosophy that informed Dostoevsky’s outlook: spiritual harmony based on freedom and unity in empathetic love. People make an active choice as individuals to cooperate.

But of course, for Dostoevsky, that love is dominated by the sacrifice of Christ. One does not have to be a Christian, however, to cherish sobornost values. At its heart, in my view, sobornost means togetherness—the opposite of destructive late-stage capitalism, which is going to burn the planet alive and us with it. We need a massive broad front of democrats (with a small d) of all persuasions to come together.

XYS: You’ve also had a prolific career as a filmmaker, and I’m curious as to how your cinematic practice intersects with your literary work; do you see any interchange or overlap between the two mediums? Does your approach to filmmaking influence your approach to textuality and narrative?

PL: I suppose my translation secret is that I see novels as films running through my head. I was very lucky as a trainee director, as I was one of the last television/film directors who learned to make films using real, physical film stock, rather than magnetic/digital tape or disk. You could hold the film in your hands and see each frame—and I actually did part of my training at Elstree studios in London.

I will often shape my text transitions as dissolves/mixes and my arguments as jump cuts! Would you believe I have a ‘novel as film screenplay’ fully translated and languishing in my PC that I cannot get published? It’s Peter Seeberg’s high-modernist 1978 classic Ved havet (At the Seaside). Seeberg was a filmmaker himself and very influenced by Beckett—another filmmaker. Ved havet has an ensemble cast and is timestamped at the side of the text, just as with film sprockets. The camera drifts between events and characters over the course of a day on the island of Rømø. In its time, tourism as a phenomenon has just hit Denmark and there are beachcombers, lovers, philosophers, and cars—lots of them—as cast members. The excellent Norvik Press in England wanted to publish the book but could not raise the requisite funds. I was chosen to translate this text, by the way, because it is so difficult to translate. I always get the tough ones.

XYS: Having translated several Danish authors, are there certain modes, genres, linguistic qualities, or methodologies of expression in Danish-language literature that you feel the Anglosphere can learn from? What is going on in the literary landscape over there that English readers should be curious about?

PL: In a way, I am the wrong person to answer this question, as I tend to concentrate on modern classics rather than current literature. But see my point above about the vernacular in Danish fiction. I think in general, the best modern Danish fiction authors like Olga Ravn and Helle Helle manage to conjure what I would call heightened realism—for whilst they are depicting ordinary people, events, and scenarios, they manage to invest mundanity with an aura of gravity and depth.

Lotte Kirkeby is another Danish author that writes evocatively about things that at first seem mundane. Her fiction metier is loss and absence, which is something that needs to be pondered. English readers can find her work in my translation of her brilliant book of short stories, The Reunion (Jubilæum, 2016).

Fewer creative writing courses and realising that a writer’s material is already out there in front of them and in their heads (just write—every day!) might be a good way of answering your question.

Paul Larkin is a journalist, filmmaker, critic, and translator from the Danish and other Scandinavian languages. In 1997, The Gap in the Mountain . . . Our Journey into Europe, the six-part film series he wrote and directed as an independent production for RTÉ, won him the European Journalist of the Year Award (the overall award and the film director category). In 2008, he was awarded the Best International Director prize at the New York Independent Film and Video Festival for his Irish-language docudrama Imeacht na nIarlaí (The Flight of the Earls) starring Stephen Rea. He lives in a Gaeltacht area of County Donegal, Ireland, where Irish is the predominant language of everyday use.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet, writer, editor, and translator.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: