Tanzanian writer Euphrase Kezilahabi (1944–2020) was a pioneer—for being one of the first Swahili poets to publish a collection in free verse, for greatly influencing the direction of the novel’s development in East Africa, for his efforts to “dismantle the resemblance of language to the world” by creating “a language whose foundation is being.” However, among East African readers, he is perhaps most known for his 1971 novel, Rosa Mistika, and the controversy that followed its publication; despite addressing the urgent themes of sexuality, violence, and women’s liberation with deftness and complex imagery, the book was temporarily banned due to its lack of moralizing on the part of the narrator. Now, over fifty years later, the English-language world will finally be able to read this stirring, poignant tale in Jay Boss Rubin’s deeply considered translation, out June 17 from Yale University Press.

In the following essay, Rubin ruminates on the iconic opening sentence of Rosa Mistika and takes us through some of the twists and turns in his translation process—illuminating also the long journey that each translator takes through the landscape of their vocation.

In a 1989 interview about his ongoing translation of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, the poet, critic, and translator Richard Howard acknowledged that some of his work was “susceptible still of revision,” but added that he was “unlikely to be persuaded to alter the opening phrase; it has become a sort of symbol, for me, of the work’s tenor (and bass).” His opening phrase, “Time and again,” corresponds to the French “longtemps,” and Howard explained his choice by describing it as “one of those cell-like phrases which sums up a meaning of the whole book.” While he had hinted at the importance of source text fidelity, I suspect that the meaning he refers to has more to do with an author’s voice. “I have tried, throughout,” he noted, “for the sound of the Proustian sentence, its tempo and suspension.”

When I first encountered Howard’s thoughts on translating a novel’s opening phrase, they helped me articulate the approaches I had taken in translating the opening sentence of Rosa Mistika, the debut novel by Tanzanian author Euphrase Kezilahabi. Writing in Swahili, Kezilahabi published six novels, three volumes of poetry, a play, and numerous short stories before he passed away in 2020, as well as scholarly texts in both Swahili and English. Among Africanists, he is well known for being one of the first writers to render Swahili poetry in free verse, and his unique talents as a poet shine through in his prose; the voice on the page is down-home, often humorous, and at the same time sparse, inviting readerly interpretation.

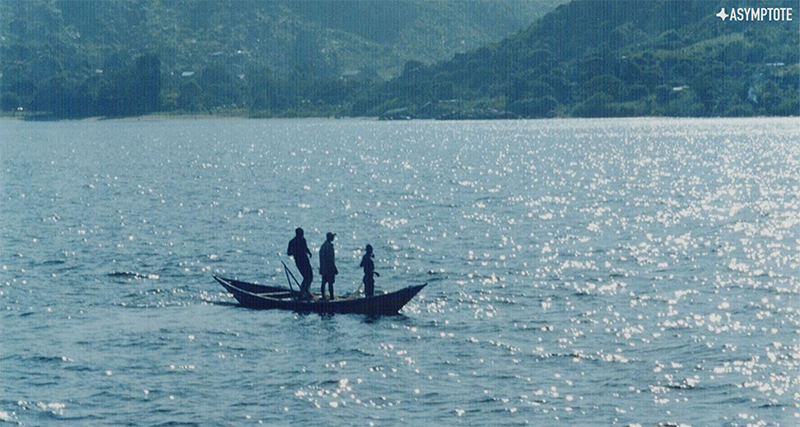

First published in 1971, the year Kezilahabi turned twenty-seven, Rosa Mistika follows the journey of the title character, Rosa, as she departs from her village on the island of Ukerewe in Lake Victoria, and ventures into the wider world on mainland Tanzania. She’s buoyed by the unconditional love of her mother, Regina, but deeply unsure about how and when to come out from under the thumb of her abusive, overbearing father. The novel was censored shortly after it was released, both for the subjects it addresses (female sexuality and abortion among them) and for its critical portrayal of authority figures (ranging from fathers and educators to government and church officials). After the ban was lifted, Rosa Mistika went on to become a staple of Swahili literature.

Kezilahabi’s legendary opening sentence reads:

Katika ziwa Victoria—kama liitwavyo mpaka sasa—kuna kisiwa kijulikanacho kwa jina la Ukerewe, maili thelathini hivi kutoka Mwanza, na kama hakuna ukungu, unaweza kukiona kutoka Usukumani.

And my translation:

In Lake Victoria—as it’s known today—there’s an island about thirty miles from Mwanza called Ukerewe. When there’s no fog, you can see it all the way from shore.

These opening lines have remained remarkably stable compared to my translation of the rest of the novel. I wasn’t aware of it on my first pass, but the approaches I took in the beginning became ones I replicated and built on, over and over again. In that sense, each of my departures from a more literal rendering are worth commenting on.

It does not take a Swahili scholar to tell that I’ve severed Kezilahabi’s lengthy opening sentence in two—a result that came after many attempts to preserve its unity. None of those early attempts sounded Kezilahabian to me, all of them having been overburdened with explanatory clauses. The phrase inside Kezilahabi’s em dashes translates to “as [the lake] is called until now,” but the word mpaka, which corresponds to “until,” is less unidirectional in Swahili. Mpaka also means “border,” and in Swahili, the temporal border of “until” can be approached from both before and after. It’s possible, I suppose, that Kezilahabi is suggesting that the name of the lake might soon change (the Democratic Republic of the Congo became the Republic of Zaire in the same year that Rosa Mistika was published), but I interpreted mpaka as pointing in the other direction: to the shadow of recent colonialism still hanging over the lake, and to the indigenous names for Lake Victoria (one of which was Ukerewe), which predate the British monarch. Using this interpretation of mpaka, it was only a small stretch from “as [the lake] is called until now” to “as it’s known today”—a phrase that minimizes potential confusion about an imminent name change, and preserves a sense of temporality around the colonial name of the lake.

Next, I condensed the drawn-out phrase attached to the island, “kijulikanacho kwa jina la” (“which is known by the name of”) to simply “called.” Efficiency can sometimes feel more literary in English. At the same time, I didn’t want to lose sight of the intentionally drawn-out, alliterative qualities of Kezilahabi’s phrase. Using tactics more metaphorical than phonetic, I attempted to replicate the author’s stage-setting elsewhere in my translation of his opening sentence.

Next, I reconfigured Kezilahabi’s geographical points of reference. In the source text, the name of the island is revealed before its distance from the city of Mwanza, but in my version, “Mwanza” comes first, followed by the name of the island. Here, there is a slight increase in drama that results from revealing the name of the island at the end of the sentence. I also think “Ukerewe” (the island of Rosa’s formation, as well as Kezilahabi’s) resonates as a final, cell-like word of the translation’s opening sentence.

Perhaps most significantly, I have obscured—or I dare say enshrouded in fog—the meaning of the Swahili sentence’s final word. “Usukumani” translates to “the place/homeland/territory of the Sukuma people.” A former Swahili instructor of mine at the University of Dar es Salaam, who is also a close friend, suggested that I try a more literal translation—like “land of the Sukuma people.” It could be an opportunity to educate Western readers about an aspect of Tanzania and its approximately one hundred and thirty different ethnic groups.

Without a doubt, Rosa Mistika involves interactions between and stereotypes about Tanzanians of different ethnic backgrounds; as such, every gesture towards the importance of ethnic identity versus national identity is important for understanding the larger, post-independence historical period in which the novel takes place—but the correspondence between Tanzanian ethnic groups and each group’s ancestral homeland is not one that translates into English very efficiently. More importantly, inter-tribal relations are not situated anywhere near the center of the novel, especially when compared to Rosa’s formation and her existence. In my reading, Kezilahabi’s reference to “Usukumani” is intended primarily to illustrate the distance and relationship between island and shore. At every key moment in Rosa’s development, she travels back and forth (either literally or imaginatively) between the two. The extended metaphor of “island-shore,” or “island-mainland,” is, to me, the central metaphor in the novel.

In his article on Swahili aesthetics, Farouk Topan—a Swahili language and literature scholar, playwright, and author of short stories—discusses various dichotomies that “characterise Swahili society,” among them “the universal ‘good/bad’, followed by ‘civilised/barbaric’, ‘coast/mainland’, ‘land/sea’, and so on,” each of which have their own “conceptual frame of reference.” Through a narrow lens that should not be confused with Topan’s, the question of whether or not an author qualifies as “Swahili” has sometimes come down to the author’s genealogical proximity to East Africa’s predominantly Muslim, Indian Ocean littoral; thus, long after his initial departure from established forms of Swahili poetry, Kezilahabi continued to face criticism that he was not “Swahili,” or not “Swahili” enough. By today’s standards, his identity should never have been up for debate: Swahili was the language he chose to create literature in, for a variety of reasons and with profound success. Another way to apply Topan’s Swahili binaries to Kezilahabi—which does not require engaging in reductive arguments about Swahili-ness—is to recall that the author was from his own coast, a different kind of coast. The fact that Kezilahabi came from an island within a lake does not automatically make his situation less Swahili.

In abstract, I agree with my old mwalimu that transforming “Usukumani” to “shore” risks losing an opportunity to educate readers about Tanzania’s ethnic groups. But in practice, and in approaching the opening sentence in particular, I prioritized setting a certain tone over imparting every possible piece of information. There are also technicalities to consider: while Mwanza is squarely within the homeland of the Sukuma, the term “Usukumani” extends well beyond the city and its surrounding environs. There is overlap but also room for distinction between “Mwanza” and “Usukumani” in Kezilahabi’s opening sentence, and similarly, there is overlap between “Mwanza” and “shore” in the opening sentences of my translation.

Perhaps most important, though, is the question of authorial intention. Stimulating thought is much more central to Kezilahabi’s artistic project than imparting knowledge. While I can’t imagine him being pleased about “Usukumani” being lost in translation until later in the novel, I can imagine him endorsing a translation approach that foregrounds Rosa Mistika’s most probing questions.

With or without “Usukumani,” Kezilahabi positions Ukerewe as an island within a lake—visible from and existing in relationship to shore. This sets the stage for investigating whether Rosa’s fate is tied to the island she comes from (the family she is brought up in, the father who watches over her), or whether her fate results from the decisions she makes herself, across the channel on the mainland of her young adulthood.

I have to look back across a foggy channel of my own to explain how I came to translate this classic Swahili novel. I began learning Swahili when I was eighteen, as a freshman in college, and as a sophomore, I was introduced to Rosa Mistika. While I originally read from the novel for language-learning purposes, it was also my first and most formative experience of what literary prose feels like in Swahili. Its cadences—the rhythm of that opening sentence and subsequent paragraphs—have been with me for nearly a quarter century. I can even point to the text from which I eventually made my translation: a photocopied version of the 1988 Dar es Salaam University Press edition that I received in a third-semester Swahili class at Boston University, back in the fall of 2001. My instructor, F.E.M.K. Senkoro, was a visiting professor from the University of Dar es Salaam, who had come to the US on a fellowship from Harvard to research Zanzibari folk tales. I’ve long thought that there was an element of good luck in him happening to pick up some extra teaching sections across the river—a luck perhaps related to my retention of the photocopied pages—and their rich remnants of literal translation—for almost twenty-five years, fifteen of them spent in utter transience.

While Rosa Mistika is a text that many Swahili-language students are introduced to at the intermediate level, Professor Senkoro may have had additional reasons for sharing it with our class. One morning, with seven or eight of us gathered around the rectangular conference table and fog still lifting off the Charles River, I asked Senkoro if he knew Euphrase Kezilahabi personally. “Ndiyo,” he answered, after a short pause. They were friends, he added. Senkoro stared ahead for another pensive moment before sharing that he enjoyed visiting Kezilahabi at his house in Zanzibar, where the author would retreat to for periods of intensive writing. I have vague memories of Senkoro describing Kezilahabi’s island refuge as a “vacation house.” Or maybe he called it a “beach house,” a term that aligns with the mysterious, perhaps fetishistic use of the English word “beach” in Rosa Mistika. Whichever way—vacation or beach—there was a level of seclusion involved.

Senkoro often spoke in a way that communicated his thinking process. I remember him sharing, in that same classroom, how his friends had nicknamed him “Nadhani,” Swahili for “I think,” because of how often he uttered the phrase during conversation. I wouldn’t have been able to put it this way at the time, but I think Senkoro thought of thinking not only as a tool to be utilized in pursuit of knowledge, but as its own kind of ontological state—not dissimilar from his friend Kezilahabi.

Via Senkoro, I felt a personal connection to Rosa Mistika long before I ever thought to translate it. He directed us to glossaries of unfamiliar nouns and encouraged us to recognize root verbs within long, agglutinative conjugations, such as the -jua (know) within kijulikanacho (which is known).

Senkoro was also the first person I ever met from Tanzania. As a result, each anecdote he shared loomed large in my imagination. For example, in Upareni, the homeland of the Pare, where he was from, it was perfectly acceptable for someone who was hungry to eat from their neighbor’s banana trees. But it was also absolutely necessary to eat them at exactly the place where they had been picked, and to leave the peels behind to acknowledge that they had been taken. To what degree these sentiments have been exaggerated in my memory is beside the point; I was a blank slate, as far as Tanzania was concerned.

Senkoro was warm and generous, but also serious and somewhat guarded. The first letter of his name stood for “Fikeni,” he told us. As for the “E,” “M,” and “K,” he promised he’d relate those stories at a later date, and warned us it might require the imbibing of a certain amount of tequila—but the drinking session never came. Senkoro seemed to have a fair amount of internal debate over what he wanted to keep private versus what he wanted to disclose. I hadn’t yet realized it, but this tendency—and need—for privacy was characteristic of his generational experience. To say without saying preserves an element of deniability, an important protection mechanism when one has reason to believe they’re being surveilled or overseen.

One day, he was explaining how the word mwana, Swahili for “child,” also acts as the prefix in various job titles and terms of relation. Mwanafalsafa is a child of philosophy, or a philosopher. Mwanaanga, a child of the sky, is an astronaut. We had recently learned the word pombe, Swahili for “alcohol,” and I asked if mwanapombe was how one would say “bartender.” He laughed. It was only a short time later that I understood that a child of alcohol would refer not to a service industry professional but to an mkata maji such as Rosa’s father, Zakaria: a serious drinker.

Another day, Senkoro described the University of Dar es Salaam—which was also where Kezilahabi studied and taught for many years—as “a city within a city on a green hill overlooking the Indian Ocean.” I didn’t recognize anything Kezilahabian in that image of circles within circles; what caught my attention was Senkoro’s mention of the university’s summer Swahili program. I ended up attending that eight-week intensive Swahili course at the University of Dar es Salaam in 2002, a decision that would have great consequences on the rest of my life.

When I returned to Tanzania in 2004—no longer a student, but a college dropout unattached to everything except what I hoped to discover, or rediscover, in Dar es Salaam—I made an unexpected excursion, midway through a lengthy trip within my trip, to the island of Ukerewe. I didn’t have any awareness that I was on a research expedition. What I took note of was a six-foot bird that looked to me like a giant pelican; a message written on a bathroom wall that read, “Asiyeweza kunya porini hana uhuru duniani” (he who cannot shit in the woods has no freedom on Earth); red lizards, said to clamp down on men’s testicles in the middle of the night; and an overheard legend about a giant nyoka, a snake, that swallowed whole ships of men in the lake.

Such observations now sound to me rather episodic, sophomoric, and no doubt hyperbolic. They may have been a mask for what I was too young or too insecure to admit: I was on a pilgrimage, having insisted on traveling to Ukerewe because of Kezilahabi’s unforgettable description of the island within the lake. His singular voice and beautiful sentences had lodged in my mind, to the point that I felt compelled to personally gaze out at Ukerewe from the shore, and then from the deck of the ferry as the island grew nearer and nearer. The literary journey that I took as a Swahili student, squinting down at those photocopied pages, led to a journey in the flesh.

After that trip in 2004, my memories of Ukerewe sat dormant for a good long while. If I, every few years, had to explain to someone what I’d been doing there, my answers would’ve grown vaguer and vaguer. But the moment I reengaged with Rosa Mistika—as a translator, this time—the autobiographical fog lifted, and my excursion to the island sprang back to life. What began as a textual relationship had turned experiential, then somehow became textual again. But I was no longer just a passenger on the ship. I was also the pilot—or copilot, rather. Ferrying Kezilahabi’s opening sentence across the channel from Swahili to English, I stayed on the lookout for navigational hazards and opportunities alike, and I repeated this journey, sifting through all of the lines in this life-changing novel, time and again.

Now, to the English-language readers curious to experience Rosa Mistika for themselves, I hope you’ll find in my translation that same sense of mystery, regarding island and shore, that once propelled me all the way to Ukerewe—and, eventually, back to Kezilahabi again.

Jay Boss Rubin is a writer and Swahili-English translator from Portland, Oregon. His translation of Rosa Mistika by Euphrase Kezilahabi was published by Yale University Press as a part of the Margellos World Republic of Letters series. Jay is a proud graduate of Queens College’s MFA program in Creative Writing and Literary Translation.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: