Humans throughout history have been fascinated by the elements. Unfathomable forces of nature, they entered our myths and minds aeons ago. There’s no time when we’re not in their thrall. Drawing from the vast store of our collective imagination across mythology, philosophy, religion, literature, science, and art, I present Elementalia, a series of five element-bending lyric essays that explores their enchanting stories and their relationship with the word—making, translating, and transforming meaning and message. This is not an exhaustive (nor exhausting) effort that covers every instance of and interaction with each element, but rather an idiosyncratic, intertextual, meditative work—a patchwork quilt of conversations with other writers, works, and texts across space and time.

Fire. Water. Earth. Air. Space. Fall in.

*

*

Everything written symbols can say has already passed by. They are like tracks left by animals. That is why the masters of meditation refuse to accept that writings are final. The aim is to reach true being by means of those tracks, those letters, those signs but reality itself is not a sign, and it leaves no tracks. It doesn’t come to us by way of letters or words. We can go toward it, by following those words and letters back to what they came from. But so long as we are preoccupied with symbols, theories and opinions, we will fail to reach the principle.

But when we give up symbols and opinions, aren’t we left in the utter nothingness of being?

Yes.

–Kimura Kyoho in Kenjutsu Fushigi Hen (On the Mysteries of Swordsmanship), 1768, epigraph found

in Robert Bringhurst’s The Elements of Typographic Style

Drukpa Kunley, the Master of Truth, himself said,

‘If you think I have revealed any secrets, I apologise;

If you think this a medley of nonsense, just enjoy it!’

Such sentiments, here, I fully endorse!–The Divine Madman, The Sublime Life and Songs of Drukpa Kunley, compiled by Geshe Chaphu,

translated from the Tibetan by Keith Dowman and Sonam Paljor

Only in silence the word,

only in dark the light,

only in dying life:

bright the hawk’s flight

on the empty sky.–Ursula K Le Guin in

The Creation of Éa, The Wizard of Earthsea

*

*

PART I

IN WHICH A LOTUS BLOOMS

Open your hand, palm up. Fan all your fingers out, stretching them away from each other like the rays of a cartoon sun. Draw your little finger down towards your wrist so the other three fingers and the thumb trail spirally in its wake. Now lift slightly from the wrist. In the south of India where I’m from, the final shape of this quick gesture means, depending on the context:

Who?

What?

How?

In other parts of the country, the same gesture may stay closed, a loose fist. Or it may open a little, the fingers uncurling, the thumb sticking up in half-hearted demand. It’s in Indian classical dance that this gesture achieves its fullest expression—अलपद्म alapadma, lotus in full bloom. When the lotus blooms, what I hear is:

Of all the people you could be, who might you be?

Of all the things this could be, what might this be?

Of all the ways this could be, how might this be?

*

*

HOW TO MAKE A GESTURE

Over the years, I’ve acquired several stretches for my hands and fingers—from simple, practical, effective ones to some that are best used as weird party tricks. But this is the gesture I return to time and again—before I pick up a pen or a brush, before I touch the keyboard. And it works.

*

*

PART II

IN WHICH I TOUCH THE SPACE

Vattam karakkunnippo elements enne, I confess to a friend re the foolhardiness of this enterprise I’ve embarked upon. These confounded elements have caught me in their vortex and I’m spiralling, getting turned around, going in circles. Keep going, he says, keep getting turned around.

Each piece takes me a long time, much to the gentle exasperation of my kind editors. A patchwork quilt must still be a quilt; the patches must be sewn together even if it’s just a running stitch that’s holding them as one.

So you see where I’m coming from: In my traditions, entire bodies of knowledge exist around the elements, teaching you how to work with them—धारणा dhāraṇās, concentrations, that come before ध्यान dhyāna, meditation. I read a lot. I let all the ideas loose in my head, let them do what they will—eat, make love, kill—and I wait. For a long time, there’s nothing, and then there’s something at the edge of my vision, a ghost of a shape, a mood. And then all at once the pressure builds, and the river floods its banks, and the words come, and they keep coming, and they don’t stop coming. It’s amazing. Kind of like the bizarre, infamous “ectoplasm” of occultists past.

“Honestly: all big conceptual questions ‘reduce to’ the deletion or compression or reimagination of specific lines in the work at-hand.” I hear you, George Saunders. Each time I leave out twice, thrice, several times as much as I put in. It’s appalling. There’s always another version that’s more involved, more complex, more sacred, more profane, more everything, and it pulls at me like gravity. “Write as if you’re dying,” says Annie Dillard in Write Till You Drop.

When I was little, I regularly wedged myself in a cracked corner between the dresser and the window, reading inadvisable books, translating bits of news from Tamil, Malayalam, and Hindi into English, recording “Space Facts” in my notebook. Valentina Tereshkova. Svetlana Savitskaya. Cosmonaut sounded way cooler than astronaut. Why stick to just stars when you can have the whole cosmos? At the bottom of the page, I wrote in my hard-won English: Touch the space. I must tuck myself into the smallest physical space in order to blow the top of my head off.

*

*

HOW TO MAKE A GESTURE

Of all the gestures. Today I pick up a brush, the biggest of the clutch. I borrow one of my dal bowls from the kitchen—I keep borrowing them for various things because the stoneware is beautiful and has a nice heft—and mix black sumi (ink) with a tiny bit of water. If I won’t drink the water, I won’t cook with it, I won’t draw with it. So it’s filtered drinking water.

*

*

PART III

IN WHICH ÆTHER APPEARS

The five great elements are together known as पञ्चमहाभूत pañcamahābhūta, भूत bhūta from the Sanskrit root √भू √bhū, to be. That which is, that which was, being, beings. The fifth element is आकाश ākāśa, sky, space, æther. That delicious ligature æ I can’t get enough of, from the Old English æsc, ash tree, and the name of the rune ᚫ it comes from, as I’m reliably informed by Harrison & Baskervill in A Handy Anglo-Saxon Dictionary: Based on Groschopp’s Grein. Its other curious meanings are: a vessel made of ash, or a small ship.

In Hesiod’s Theogony, Chaos was the first. And from Chaos sprang forth Erebus, darkness, and Nyx, night. From them appeared Æther, brightness, brother of Hemera, day. “Chaos should be regarded as extremely good news,” says Chōgyam Trungpa. I’m building a ship of ash, to pursue the light through the long dark chaos.

*

*

HOW TO MAKE A GESTURE

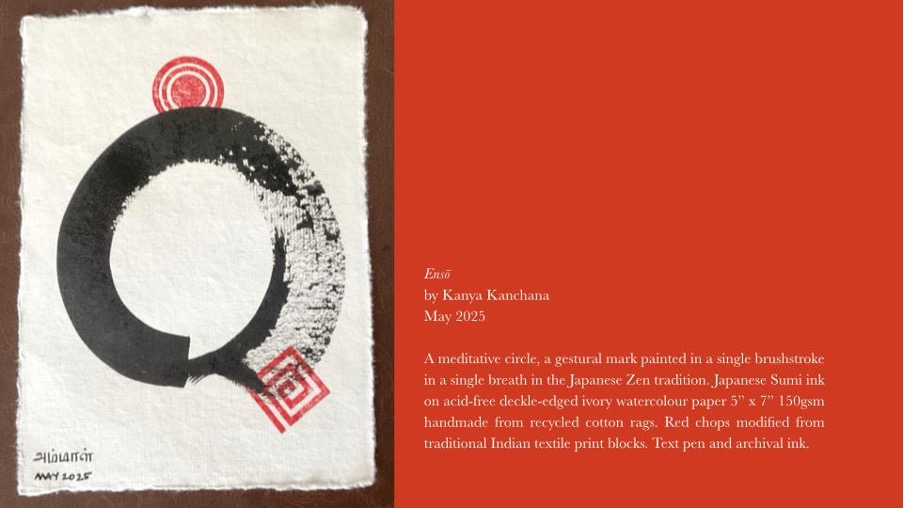

I don’t recall whether it was Thích Nhất Hạnh I read on the subject first, or Chögyam Trungpa. A circle drawn in a single breath, the text said, in a single brushstroke. Ensō. There are bits of knowledge that go in one ear and right out the other, and there are bits of knowledge that go off like a bomb in the head. The ensō was a bomb. And I was primed for incineration.

*

*

PART IV

IN WHICH I ENTER THE BARDO, OR THE INBETWEEN

(a silly micro on the Tibetan Buddhist funerary text called Bardo Thödol, commonly known as the The Tibetan Book of the Dead)

I’m not innocent. Come to think of it, it’s likely that I’ve never been innocent. In fact, I’ve always been told I’ve got a certain look in my green eye—the look of the cat that (allegedly) got the cream. But: questions of cream and its legitimacy are now moot because I’m dead.

Yeah, this guy here, this goodly priest fellow, has been telling me exactly that over the past several days. In several ways, just in case I was obtuse or something.

You think I’m being flippant about this whole process, I can tell. I’m not. It’s just—how would being serious help right now?

Okay, okay, okay, I know I’ve fucked up. I’m not getting enlightened or liberated or whatever this time around. So that means I’m going to have to choose where and to whom I’m going to be born. Can you imagine the responsibility?

It’s not like I can hire an astral private investigator to check out my future parents’ backgrounds—genetic anomalies, hereditary diseases, criminal records, credit scores, familiarity with the dharma, I don’t know. Do they have a good home? Are they good people? Are they going to take care of me? Oh wait, are they even human?

Ahh, I know I should’ve paid more attention when they were talking about stuff like this. Well, they’re calling my number now. I’ve got to go.

Hey, have a drink on me, will you? They’re free.

*

*

HOW TO MAKE A GESTURE

My own spiritual traditions lie elsewhere, but I’m drawn to certain Zen practices. This damned, blessed circle is one of them. I’ve been drawing these circles on and off for years—in charcoal, in pencil, in pen, in mascara, in ink, in paint. Drawing over coffee cup stains. Tracing around lids of tubes, jars, big-ass cylinders. Filling an entire notebook of two hundred pages with circles after crappy circles in one sitting once. Feeling a bit relieved to learn later that Shunryu Suzuki did something similar to get some poster art right. Drawing the sun and the moon at the same time, drawing emptiness and fullness.

*

*

PART V

IN WHICH A GOD TURNS INVISIBLE

I have an old scanned book called Chidambaram and Naṭarāja: Problems and Rationalization by BGL Swamy. He says, vexed, in the preface: “Unfortunately, as there has been an undercurrent of reverential feeling, the writings mostly are a medley of history and legend, permeated by sentimental and emotional observations. . . . The delineation of these perhaps requires freedom from pious feelings an object of reverence engenders.” The original reader called Ulakanathan (in his formal Tamil seal), or Olaganathan (in his own hand), has drawn a sigil of sorts in several places. A spiral from which grows a flame, above which hovers a mysterious drop of something. His name means “lord of the world.” I hear it clear as a bell, transmuted to Olahon! “world.” Give it up, Swamy. The world has ruled.

Scholar and art historian C Sivaramamurti says, describing the five faces of Śiva: “The most prominent of the five faces of Śiva as Sadāśiva are Tatpuruṣa, Vāmadeva and Aghora facing east, north and south respectively. The other two are Sadyojāta and Īśāna, the former facing west and the latter upwards. Again in this order they represent the five elements, earth, water, light, air and ether respectively. . . The last and the holiest is imperceptible like ether and [they] usually show only the rest of the four. . .”

In the stunning cave temples of Elephanta—a ferry ride out from Bombay Harbour and partially destroyed by Portuguese cannons—you can still see Śiva’s beautiful, visible faces. And in the sanctum of the old temple at Chidambaram, a veil. The veil is माया māyā, expediently but incompletely translated as “illusion.” What’s behind the veil? आकाशलिङ्ग ākāśaliṅga—formless form, empty space, and a few golden vilva leaves. “If space goes naked / with what / shall they clothe it?” asks Allama Prabhu, translated from the Kannada by AK Ramanujan in Speaking of Śiva.

The secret of Chidambaram, for those with eyes.

*

*

HOW TO MAKE A GESTURE

Like a Japanese train conductor or a factory worker performing shisa kanko, pointing-and-calling, I point my juicily loaded brush at the watercolour paper on my desk, then touch its wooden end to my temple. I’ve been using this technique from before I knew it was a thing, with a name. Stove off, lights and fans off, door locked—piu-chiuk, piu-chiuk, piu-chiuk. And it works. The paper is blank but the circle has already been made. I only have to follow its movement in the empty space, to touch it to paper.

*

*

PART VI

IN WHICH A SAGE ANSWERS QUESTIONS

“Gārgī asked first with what weft time (‘that which is called past, present, future’) was woven. Yājñavalkya answered: ‘with the weft of space (ākāśa).’ But Gārgī still had her second and last question in reserve: ‘With what weft is space woven?’ At this point Gārgī might have been expecting a blunt refusal to answer, as on the previous occasion, together with the threat of death. This didn’t happen. Indeed, Yājñavalkya’s answer was immediate and expansive. He said that the weft of space was woven on the ‘indestructible’ (akṣara),” Roberto Calasso in Ardor.

What is this आकाश ākāśa that Gārgī, the weaver, received in answer?

“One passage in the Chāndogya Upaniṣad states all this (a revelation that shatters all previous thinking) in the quietest, most direct way, as in a calm, persuasive conversation: ‘That which is called brahman is this space, ākāśa, which is outside man. This space which is outside man is the same as the one within man. And this space within man is the same as that inside the heart. It is what is full, unchangeable.’ ”

I hear one of my teachers, his voice clear and resonant: चिदाकाश cidākāśa, the inner space of consciousness. And then another, her voice older, kinder: हृदयाकाश hṛdayākāśa, the space within the heart. ஈரம் īram, she says, it’s a little wet.

And what is अक्षर akṣara, the imperishable? In one of its many forms, it’s the letter, the kind that makes words.

*

*

HOW TO MAKE A GESTURE

“I sometimes grow weary, however, of the monocultural, mono-religious, and mono-gender character of traditional monochrome circles executed on a manageable scale. The enso, or circle symbol, appears to be monopolized by accomplished East Asian Zen masters, executed with black ink on white paper,” says Kazuaki Tanahashi in Painting Peace.

Wait! I’m coming! I’m getting there!

*

*

PART VII

IN WHICH A YOGI CUPS A HAND TO HIS GREEN EAR

“Nāda, primordial sound, is the basic momentum or ‘substance’ from which the world is made. It is the prototype of sound, and the condition necessary for creation to take place. Ākāśa, ether or space, the first element of manifestation, has sound for its quality,” says Stella Kramrisch in The Presence of Śiva.

Whenever I walk around the stupa in Boudhanath, Kathmandu, my eyes are drawn towards the traditional meditation thangkas and paintings in the shop windows. I walk into one of the shops along the outer circle to ask about a painting of Milarepa in the window. They haven’t got any prints and so I take a picture instead.

Milarepa, the greatest yogi of Tibet, green from all the stinging nettles he loves to eat all day, is most often seen cupping a hand to his ear, catching वैखरी vaikharī, the uttered word moving through space. Like आकाशवाणी Ākāśavāṇī, voice from the sky, the name Rabindranath Tagore lent to All India Radio.

But the word is not the only thing moving through space. Across the vast expanse, mysterious female beings of great yogic powers—called डाकिनी ḍākinīs in Sanskrit, or མཁའ་འགྲོ khandro in Tibetan, ones who move through the sky. The same root word ख kha, sky, space, is seen in खेचरी khecarī, sky-goers. That’s right: skywalkers.

My Milarepa looks a bit old, a bit tired, and his green is tinged blue. I’ve read his wild stories, heard his songs, been to his cave. He says: “First I committed evil deeds. Later on I practiced virtue. Now I am free from both good and bad deeds, and having exhausted the bases for karmic activities, I will not conduct them in the future. Were I to explain these events at length, some would be reason for laughter, others would be reason for tears. Such discussions are of little use, so let this old man rest in peace.” Tsangnyön Heruka in The Life of Milarepa, translated from the Tibetan by Andrew Quintman.

Rest in peace, you crazy old man. You’re loved.

*

*

HOW TO MAKE A GESTURE

“For the practice of creating of an ensō, there should be no hesitation and anticipation in its application, but a fearless yet mindful attitude. Just as with the practice of meditation itself, the ritual of creating an ensō is also a practice of meditation in action.

As once the brush loaded with ink strikes the paper, there is nothing more to do but follow through in undistracted present awareness, while mastering control of the arm and hand from the core of one’s being in heart and mind,” says Tashi Mannox, a calligrapher whose work seems perfect to me.

“It is taught that ‘perfection is in the imperfection’ as there should be no attachment to the created ensō, resulting beautiful or ugly, but a mere recording of that moment in time, which nakedly reveals the state of mind, honest and pure.”

Small mercies. I’m still at the uglies.

*

*

PART VIII

IN WHICH A PHILOSOPHER GIVES ME FOUR PROPOSITIONS

“The ship on which Theseus sailed with the youths and returned in safety, the thirty-oared galley, was preserved by the Athenians down to the time of Demetrius Phalereus. They took away the old timbers from time to time, and put new and sound ones in their places, so that the vessel became a standing illustration for the philosophers in the mooted question of growth, some declaring that it remained the same, others that it was not the same vessel.”

From Plutarch’s Lives, Theseus 23.1, translated from the Greek by Bernadotte Perrin, this is what has come to be known as The Ship of Theseus, a famous philosophical paradox.

A fourth-century Buddhist philosophical treatise called महाप्रज्ञापारमितोपदेश Mahāprajñāpāramitopadeśa (Great Instruction on the Perfection of Wisdom), or Dà zhìdù lùn (in classical Chinese, translated by Jing Huang and Jonardon Ganeri), discusses something very similar—albeit in a much more gruesomely interesting way. Although we don’t know which came first, the crossover is understandable because Alexander invaded India in 325 BC, and later, a Graeco-Buddhist tradition grew around Menander who is known to have spoken with Buddhist monks.

A traveller comes across two demons, one of whom is carrying a corpse. They proceed to dismember the unfortunate man limb by limb, replacing each limb with the corresponding one from the corpse. “What has become of me?” he cries, when their sport is complete.

“OK, so the term conceptual breakthrough is sometimes used in science fiction criticism to describe the moment in the story in which a character’s understanding of their universe changes in some fundamental manner. They are experiencing a sort of paradigm shift about their place in the universe. I think that’s a way of dramatizing the process of scientific discovery. A conceptual breakthrough is different from a personal epiphany,” says Ted Chiang.

Nāgārjuna, to whom this text is (“traditionally, though certainly erroneously”) attributed, is the kind of guy who will give you four options when you’re already worried sick about two. Tetralemma, double the dilemma. X, yes. Not X, no. X and Not-X, both. Not X and not Not-X, neither. Form, experience, and then some.

*

*

HOW TO MAKE A GESTURE

There are these artist seals—“chops,” they’re called—traditionally made out of jade or soapstone, with signatures, inscriptions, or images carved into the stamp. They’re dipped in red ink and applied to the artwork upon completion. I’ve sketched out several and am in the process of making them out of rubber stamps, textile print blocks, and whatnot. I hear soapstone is easy enough to carve.

*

*

PART IX

IN WHICH BORDERS ARE CROSSED

I owe Calasso a great debt—his work has given and continues to give me a new way of thinking, new eyes.

He wrote a last unnamed book before his death: Opera Senza Nome. No English translation exists at the moment, but the synopsis on the website says: “In the end, I have done nothing more than attempt what every writer, more or less obviously, would like: to invent something that did not exist before. The idea was that each of these books would be self-sufficient, readable as a whole, but intertwined with the others through connections of all kinds. Something where what separates the individual voices is much larger than the voices themselves, similar to islands in the current of a limitless sea. Each time, in those islands, the style is different, as if they were home to vegetation that partly repeats itself. Only the current that supports the whole is unique.”

Creativity is an isometric exercise—you must push and pull, work against something. It doesn’t exist in a vacuum. The islands must resist the limitless sea and love the limitless sea or nothing green will ever grow.

In discussing the intertextual peculiarities of this series, writer Lisa Wells astutely directs my attention to David Shields’s Reality Hunger and sends me a quote from one of his interviews: “In a way, my position is somewhat heretical. I’m actually saying how it feels at ground level to write a work of book-length essay. I’m acknowledging what you’re not supposed to say: composition is a fiction-making operation. Memory is a dream machine. I’m trying to say that a work of essay ought to be viewed for its depth-charge: how much verticality it has, how deeply it investigates the issue it’s exploring. . . . And so there’s a ton of straitjacketing: let’s all be dutiful citizens and write our vetted memoirs, our sober scholarship. What gets lost is artistic transgression, boundary jumping, our moving forward.”

This is what I’ve attempted with this series—crossing boundaries, discovering connections that exist, making connections that don’t yet. Gleefully running my island ferry, and on occasion, falling headlong into the sea without a lifejacket.

*

*

HOW TO MAKE A GESTURE

“The monument par excellence of ancient India is its language. It is in verbal matter that the ancient Hindus carved their Pyramids, their Sphinxes, their Ziggurats,” says writer Rene Daumal. “They left no objects or images. They left only words. Verses and formulas that marked out rituals. Meticulous commentaries that described and explained those same rituals. . . Only texts remain: the Veda, the Knowledge,” says Calasso, speaking of the Vedic people in Ardor.

What does it mean for an entire civilisation to disdain conquests and material victories, to be apathetic to empire, to be unconcerned about its own history seen in retrospect and cut to alternate measures, and instead: to care about, and only about, knowledge? Nothing else was considered worth bequeathing. Even the paraphernalia of essential ritual sacrifice were dismantled and often destroyed afterwards. What a high-wire act.

*

*

PART X

IN WHICH I EXIT THE BARDO, OR THE INBETWEEN

(the silliness continues)

You saw me last when I was in my bardo, isn’t that right? The womb of the world, so to speak.

Hey, listen carefully to what I’m telling you right now, because I’m about to forget everything real soon. Can’t get you a drink this time, though, they’ll only give me this stupid milk.

When your memory spans just the one lifetime, birth feels great and death feels awful. You know that. But when you’ve done it over and over, hundreds of times all over the multiverse in every imaginable form, you really, really don’t want to do it again. It’s just too much, all that feeding and fighting and fucking and working and suffering. Just the never-ending living. Sure, every life’s got some good bits, but on balance, eh. And that’s why I was so freaked out about the whole thing in bardo. Because I’d failed yet again at making it stop!

But I must say, being a foetus wasn’t all that bad. Or at least, not as bad as I remembered it. It was like being in a warm, self-sustaining, subterranean pool—both ancient and futuristic at the same time. And when I paid close attention, I could actually feel my wetware taking shape within the soft cloud of my body, feel myself becoming something. I was so snug in my pool and had even wrapped my cord a couple times around my neck for warmth that what came next was such a rude shock! This is the bit I forget every single time—the insistent pressure to get out now, like you’re some houseguest who’s overstayed his welcome, the unstoppable flood of water and blood and slime, the unbearable surge of light and sound and air.

But this time—you’re not going to believe this—I floated up into water. A beautiful, bloody, long-stemmed lotus I was, floating at the end of my umbilicus, maker of a whole new world. The sheer baroque maximalism of the thing, the sumptuousness of uncontainment, the vast bloom—I don’t mind telling you I cried.

*

*

HOW TO MAKE A GESTURE

In contemporary writing, when it comes to endings, a lighter touch is favoured. Don’t package your ending. Don’t put too fine a point on it. Don’t go on forever. Don’t. I can understand that. It is kind of nice to just leave it there and step elegantly off to one side. But I’m also interested in the older traditions of clear, ritual beginnings and endings, and what they accomplish.

*

*

PART XI

IN WHICH SOMETHING CROSSES OVER

By early afternoon, Tsomgo has frozen over. The glacial wind howls over the pristine white expanse of the lake. The yaks tuck their massive heads close to their chests and stand very, very still. I catch a perfect snowflake in my glove. And then I run into the nearest shop where warmth and companionship beckon.

We’re returning from Nathu La, a border trading post at the mountain pass between Sikkim and Tibet, part of the Old Silk Route. The Chinese guards on the other side of the barbed wire had tried to look sharp as windchill shaved a few more degrees off the temperature. One of them had held up two fingers in the universal gesture, a smile crinkling his eyes: Got a smoke?

The shop is just one of those you find everywhere along the mountain roads. Held up half by precarious contraptions and half by reckless optimism, they have one central feature: a long wooden table, cracked and peeling. A thick iron cylinder with a conical top is set into its middle. Upon this device sits a tall, roof-piercing flute that serves as a chimney for the fire within. They serve tea, coffee, biscuits, instant noodles, and slap you away if, in your brainfreeze, you try to roast your appendages. Winter in Sikkim. If you look at a map of India, you’ll see this old mountain kingdom nestled snugly between Nepal, Bhutan, and Tibet.

I take my place at this table. My teeth start to chatter. I look at the little girl sitting across from me. She couldn’t be more than three. Unruly wisps of brown hair cling about her tiny face. Wordlessly, she takes off her single mitten and lays it on the cracked table. Caked with dirt and grime, it must’ve been pink once. I could hold it in my palm with room to spare. I hide my smile.

She gets onto her knees on the bench. Reaching across, she takes my hands between hers and rubs them earnestly. Ah, what.

There’s a noise and I turn my head for a second. She’s gone. No girl, no mitten.

“Have you seen a little girl, yay big?”

“What girl?”

“She was just here. Very young.”

“No, it’s just you.”

In a photo taken just after, my eyes glitter like gems.

*

*

HOW TO MAKE A GESTURE

The circle is complete, the serpent that eats its own tail. That which is empty, śūnya, and that which is full, pūrṇa, are not different from each other. “I cannot tell if the day / is ending, or the world, or if / the secret of secrets is inside me again,” says Anna Akhmatova.

I put down my brush and stretch my hands. In the brief oxygenated pause, the lotus blooms. Have I told you yet—the gesture also means Why?

Sometimes the answer to all the questions is again the same gesture, and now it means:

Who knows.

*

*

PART XII

IN WHICH THE CENTRE OF THINGS

Some people say, shaken by the toomuchness of things—oh, this makes me realise how insignificant I am. I have never understood this. But I know a few places significance may be found.

[ deep in the ocean / or at the meeting of three / in the star-carved night / behind your eyes / in the spinning of the top / in the parch of riverclay / up a thousand stone steps / on the mountain made cloud / in the humid prayer-lit cave / in the belly of the serpent / in the raindrop on your lash / in yellow rubber boots squelching in mud / in all the words for rain / in your safe green place / in the arterial spurt from the neck of the buffalo / in the thrum of ten million people at once / in the raggedy tent dancing before dawn / in the faded hem of the old cotton dress / in the turn and fall of the pipal leaf / on the night train racing the moon / at the burning ghats / in the owl large as a child hollow-boned and perfectly dead in your arms / on the roof of the bus ducking under branches / in the fur of the yak / in the high hum of the market / in freshly gathered greens / in chopping plump tomatoes / under low and high ceilings / under no ceilings at all / in the undersound of the tiger / in the held breath / in love / in the snow on your tongue / in the doings of love / on your naked skin / in liquid pine resin / in the pot of boiling water / in shock / through your spine / in lightning that cleaves the banyan in two / with the crossed palms of the dead / inbetween / in the throat of the monkey asking for your guava / in the music of strange lands close in your ears / in code / in walking on hot coals / on the sharpened blade / in the glut of the overripe mango / in the absurd decadence of peacocks in thorn shrubs / in time moving through your fingers / in time going nowhere / in the corona of the automobile crash / in your white white bones / in the tide of sound / in your red red blood / underground / in the shower / in yes / in the others that you are / in the others you think you are not / in the permeable membrane / between adream and awake / in fever / in no / in the blue hour / in the temple from before your time / in the slowing of the top ]

You must read what is written in ink, in stone, in feather, in dust dancing in the path of sunlight, in the curl of the little finger, in the sealed letter, in the turn of the lip, in the crease of the elephant’s eye, in water, in the bark of cedars, in muscle and sinew, in fire, in closed faces, in the wheeling of stars, in air, in the warm palm on your head. Read without a sound.

You must want to know so badly as to stand on the edge of madness. You must hear what they say—when you look long into the abyss, the abyss also looks into you. You must know—the only way you can look into the abyss is to let the abyss look into you. You must die and be reborn. You must laugh and cry and shake like a leaf in terror and then laugh again. You must not be so much you that you cannot be all things—living, breathing, moving through the cosmos in so many ways.

Your mind must bend at the scale of it, but not break. Your mind must be blown, but not apart, by the unspeakable, terrifying beauty of it. You must not fail to feel its significance in your brain, in your body, in your toes, all ten digging into the earth.

You must walk, walk with the power of your lungs and your own beating heart. Walk with others—with ancestors, with teachers, with friends, with lovers, with strangers, with children, with animals, with trees—and with yourself, through the day and especially through the night, feet callousing, fingertips buzzing, hair flying. Walk until one day the sun breaks over your head bright and unequivocal. And then again and again and again until your own head breaks like a coconut and—nothing, nothing, not even you can stop it—the whole multiverse flows in and out. And in this golden hour, you step over this pool of water, open this blue gate, sit on this bench under this flaming gulmohur, in this place fit for kings and queens.

And you are exactly where you must be, doing exactly what you must be doing. There is nowhere else you would rather be. There is nothing else you would rather do.

You are in the centre of things.

You are the centre of things.

This is it.

*

*

HOW TO MAKE A GESTURE

“What a life, what a night / What a beautiful, beautiful ride / Don’t know where I’m in five, but I’m young and alive / Fuck what they are saying, what a life,” Scarlet Pleasure in my headphones. And in the film, Mads Mikkelsen, no longer young and very much alive, dancing that sublime dance.

Had I been a good writer, I might’ve written a single book. Had I been a better writer, I might’ve written a single poem. Had I been the best writer, I might’ve written a single word. Had I known what I was doing, I might’ve said nothing at all.

*

*

ॐ पूर्णमदः पूर्णमिदं पूर्णात् पूर्णमुदच्यते ।

पूर्णस्य पूर्णमादाय पूर्णमेवावशिष्यते ॥

ॐ शान्तिः शान्तिः शान्तिः ॥oṃ pūrṇamadaḥ pūrṇamidaṃ pūrṇāt pūrṇamudacyate ।

pūrṇasya pūrṇamādāya pūrṇamevāvaśiṣyate ॥

oṃ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ śāntiḥ ॥Om

That is whole. This is whole. From the whole arises the whole.

When the whole is taken away from the whole,

that which remains is the whole.

Om peace, peace, peace.–शान्तिमन्त्र Śāntimantra from the

ईशावास्योपनिषद् Īśāvāsyopaniṣad

*

*

Image information:

- Opening image: My hand reaches into empty space. Singapore.

- Closing image: Ensō.

- Message excerpts throughout the piece are anonymised bits from conversations with friends discovered in my ancient chat archive, and (only my side) used in the manner of found objects.

Kanya Kanchana is a poet and philologist from India.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: