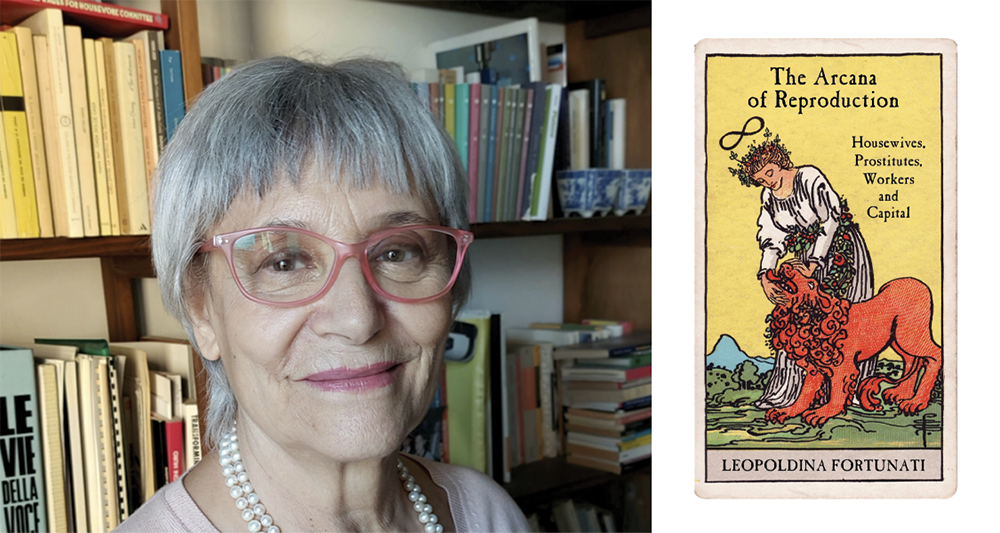

The Arcana of Reproduction by Leopoldina Fortunati, translated from the Italian by Arlen Austin and Sara Colantuono, Verso, 2025

Earlier this year, Indian Twitter spiralled into a full-blown meltdown after Mrs., the Hindi remake of the Malayalam film The Great Indian Kitchen, was released pan-India on the streaming platform Zee5. The film provides a picture of the world of Richa, a well-educated woman who recedes into the drudgery of housework; after marriage, her dreams and desires suffocated. I could not bring myself to watch the film, but I devoured the reviews. Many hailed the movie for its realistic rage against the patriarchy, but the bones of contention that the audience picked with the film were many. One Twitter user casually remarked that if the husband is the breadwinner, the least one may expect from the wife is to do the household chores. Reading these reviews and blithe takes, I was livid, and I could not quite put a finger on why.

I found the answer, cosmologically-willed, in Leopoldina Fortunati’s work L’arcano della riproduzione (first published in 1981), rendered into English by Arlen Austin and Sara Colantuono as The Arcana of Reproduction. Fortunati was a key member of Lotta Femminista, initially called Movimento di Lotta Femminile (Women’s Struggle Movement), and then finally Movimento dei Gruppi e Comitati per il Salario al Lavoro Domestico (Movement of Groups and Committees for Wages for Housework). English-speaking countries are more familiar with its alternative name: the network of Wages for Housework. As the name suggests, the international movement had a militant and anti-capitalist dimension, and its goal to secure pay for housework aligned much with the struggles for wages that were playing out in factories and universities at large. Together with companions Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James, and Silvia Federici, she wrote texts that reflected the movement’s goals and ideology; her Arcana of Reproduction emerged from these reflections.

Any reader who ventures to read Arcana of Reproduction should be familiar with Marxist terminology. Delving into the text without any prior knowledge of Marxist thought may prove to be a futile exercise, for the very preoccupation of the book is with its theory of reproduction and reproductive labour, in particular the consideration of domestic work and prostitution, as indicated in the book’s subtitle: Housewives, Prostitutes, Workers, and Capital. The work is a practical extension and an important intervention by Fortunati to address Marx’s lopsided consideration of the feminist question, and consequently a response to the male left, achieved by breaking free from the chokehold of theory and situating oneself in reality, the “practical needs of feminist struggle” and the “specific reality of women’s lives.”

Fortunati begins by introducing the structural transition from pre-capitalist to capitalist modes of production, and in doing so, how capitalism underappreciates individual reproduction by prioritising the creation of value. What happens then is the invisibilisation of reproduction next to value, which renders the two separate—almost opposite. In that, reproduction becomes natural and appears as a non-value. Because the two are posited as opposites, the laws that govern reproduction are “very different” from the ones that govern production. To quote Fortunati, “reproduction appears as the mirror image, the photographic negative of production,” and the subject of this negative is the woman.

It is through this photographic negative that Fortunati sweeps us into understanding the re/production economies of the housewives, the prostitutes, and the workers. Consider the paragraph:

. . . the man/woman relationship is not a relationship between individuals, even if it is represented as such. It is a relationship of production between women and capital mediated by men. It is a complex relationship, played out through duplicity, and notable for the contrast between its representation on levels of the formal and the real. This complexity is obviously reflected in the exchanges presupposed by this relationship.

The paragraph troubles the relationship between man and woman by pitching them as unequal in the circuit of capitalism. Fortunati, here, sharpens attention towards the unseen, unacknowledged labour that a woman does in the capacity of housewife or prostitute. They are doubly jeopardised—subservient to capitalism, and subservient to men, the waged male worker. Even in their subservience as housewife or as prostitute, women are not equal, for “woman as housewife is not in an equal relationship with the worker, the prostitute is even less so, because she pays for the money she earns with her own criminalisation.” Fortunati also notes that it was during the Second World War that wage emerged as the site of struggle between the housewife and the waged male worker, where the former demanded that they be handed the paycheck. While the management of paychecks may have been casually dismissed as “a rational management of consumption,” it could mark the first instance of “anti-capitalistic management” of male wage—one that allowed women to think of themselves, however briefly, by booking weekly appointments with their hairdressers.

Fortunati’s thesis is provocative, and particularly so in her chapter “The Hidden Abode: On the Domestic Working Process as a Process of Valorisation,” in which I found the reason for my lividness at the reviews of Mrs. She breaks down the process, from the most elementary labour that is procreation, to demonstrate how capitalism’s goal is not to dispossess women of their bodies but rather to take control of their bodies, notably their right to reproduce—their uterus. Fortunati comments that Marx’s critique of capitalism eclipses this important aspect of women’s work, the reproductive labour power. Even love is work, for “domestic labour is not only labour that satisfies, within given limits, the material needs of the individual’s belly, but is also labour that responds to immaterial needs.” She deftly raises the question of time, where the houseworker’s labour power as non-value is chained for an indefinite period, bringing to one’s mind Julia Kristeva’s theory of “Women’s Time.”

Adopting the language of consumption and production, Fortunati scrutinises the affective registers of domesticity, where “the man is selfish because he consumes love, while the woman is generous because she produces love. But how does she produce love? She does not do so freely, outside of a working process, but within the process of domestic labour to produce a commodity: labour power.” It is here that Fortunati is at her explosive best—she argues that sentiments and sex are “not necessarily natural” and that any sentiment that we work with as women, or consume as men is “fabricated”—and this is made evident through the existence of women who refuse to live with men even with whom they are in a relationship or in love. She applies the logic further to filial relations, parental and sibling, to highlight the existing unequal power play within them. These arguments are instrumental in proving her point that capitalism tends to benefit from the servitude of two at the cost of one, and this forms the content of the chapters that follow, where she plunges into Marx’s oeuvre to demystify the question of women’s labour in his writings, thereby attempting to recuperate and bring to the fore the necessity of addressing the reproductive labour of women as productive.

In a befitting afterword that also serves to pronounce the continual relevance of the book four decades after its initial publication, Fortunati notes that while a lot may have changed since its conception, women are not yet liberated from the nexus of reproductive work and capitalist relations. For instance, digital mediation, contraception regulation, abortion laws, the failure of the State to regulate laws, and the gendered notion of duty and caregiving abilities are just some of the ways through which women’s work continues to be withheld currency and is consistently undervalued. It is also important to note that Fortunati acknowledges the limitations of her scholarship. By focusing extensively on a heteronormative family model, she fails to register significant interventions and solutions that may have been afforded through an intersectional lens.

Given the density of the content, reading the book was a laborious task, but it was rendered undemanding by magnificent degrees through the astute translation of Arlen Austin and Sara Colantuono. Reading their translators’ note proved to be the most helpful exercise before I immersed myself in the text. Their existence on the margins—as footnotes—functioned no less than faithful companions, ready to rescue you from the dense abstractions of values, wages, and the broader architecture of textual capitalism. Their timely translation qualifies this book as a work of worthy rumination. While the work is bound to unsettle the sensibilities of certain readers who romanticise matrimony, love, and other sentiments, it may also materialise as an important document to organize, educate, and liberate women—one that speaks to the tarot card on the cover of the book, the Arcanum Eight of Strength, where “your job is to make sure you are talking to yourself with love and support so that you feel safe enough to make different, better choices.”

Sonakshi Srivastava is a senior writing tutor at Ashoka University, the translations editor at Usawa Literary Review, and an educational arm assistant at Asymptote. Her writings have generously been supported by the 2024 ASLE Translation Grant, Director’s Fellowship (Martha’s Vineyards Institute of Creative Writing), Diverse Voices Fellowship, and the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts. She can be found on X and Instagram.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: