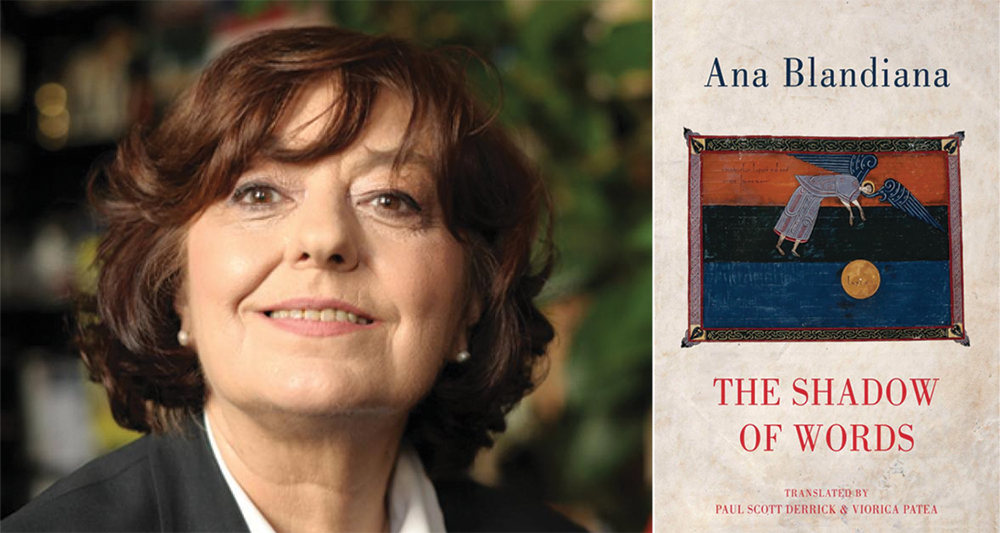

The Shadow of Words by Ana Blandiana, translated from the Romanian by Paul Scott Derrick and Viorica Patea, Bloodaxe Books, 2025

Before entering into Ana Blandiana’s The Shadow of Words, a compilation of the lauded poet’s early work, my first task must be to praise the lengthy introduction by the collection’s translators, Paul Scott Derrick and Viorica Patea, in which they give a superbly lucid account of the intricate shifts in the poet’s sensibility in these beginning years, from 1964 to 1981. The overarching theme, they ascertain, is the various ways that Blandiana stages relations between the joys of intimate life and the political order that threatens them. It is fascinating how these poems elaborate variations on those attitudes.

A poet familiar with the realities of social life. Blandiana was banned from publishing in her native Romania at only seventeen years old, and prohibited from going to university because her father, an orthodox priest, was considered a political prisoner by the communist regime—leaving her labelled as “an enemy of the people.” Later in life, her rebellions against the Ceauşescu dictatorship led to further prohibitions against publication in 1985 and in 1988, with the latter lasting until the revolution of 1989. Such political and literary efforts have since led to her becoming a legendary figure in Romania, often seen as a Joan of Arc or a modern Cassandra—while in her literary oeuvre, she is comparable to writers like Vaclav Havel and Anna Akhmatova, whose work has become symbolic of a collective destiny.

Describing her first volume, First Person Plural, Derrick and Patea note that it is mostly concerned with “the frenzy of living in harmony with nature’s rhythms,” by means of poems “that celebrate life with an effervescent energy.” Their basic example is a short passage from “Rain Chant,” included here in The Shadow of Words, where there are indeed subtle and evocative treatments of those forces. This poem opens with:

I love the rain, I love the rain with passion,

The madcap rain, the quiet rain,

The virginal rain and the rain like a hot-blooded woman,

The sudden shower and the endless, boring drizzle.

I love the rain, I love the rain with passion.

I like to wallow in its tall white grass,

I like to cut its blades and press them between my lips,

Let men get dizzy when they see me like this . . .

Here, the enthusiastic expressions of love correlate with objects the speaker “likes,” as if the expansion of subjective life allows poetry to find its anchors in perception—with the subjective and the objective intensifying one another. When “men” are then introduced, it subsequently suggests a subplot where the youthful speaker begins to feel what she can bring to the budding states of sexual desire, or at least to modes of desire that will have romantic consequences. All these elements become more dominant in the close of the poem, sustained brilliantly by Blandiana’s capacity to produce a plausible voice, to directly address the possibility of a “you” capable of sharing these emerging passions:

In rain like this you can suddenly fall in love,

Everyone on the street has fallen in love,

And I am waiting for you,

Only you know—

I love the rain,

I love the rain with passion,

The madcap rain, the quiet rain,

The virginal rain and the rain of a hot-blooded woman. . .

Whereas in the beginning the speaker seems young and naïve, the ending sees her as someone capable of focusing on a “you,” allowing her to see herself as this “hot-blooded woman,” ready to extend how she loves.

This sense of celebration, however, was not to endure very long. By Blandiana’s next volume, she has found herself caught between “the realm of purity” and of eager desire, apart from the realities of social life, and debasing herself “under the law of life, which her dignity rejects.” Derrick and Patea demonstrate this aspect of Blandiana’s sensibility by citing a superb passage from the poem “Intolerance”:

I want clear tones,

I want clear words,

I want to feel the muscles of words with my hand

I want to understand what you are, what I am,

And clearly distinguish a laugh from a curse.

This is the same kind of direct voicing we saw in the aforementioned “Rain Chant,” but now there seems to be an inescapable divide between her own grasp on reality (feeling “the muscles of words”) and her capacities for exercising empathy (the ability to “distinguish a laugh from a curse. By this point in her career, Blandiana is subsumed with the desire to directly address social situations, trying to find plausible ideals by which to help readers change social behavior. In her third collection, The Third Sacrament, her work modulates into a quest for metaphysical foundations, focusing on ideas of “transubstantiation and love.” But the distance between ideals and social realities gives this volume a pervasive sense of melancholy. The poem “Humility” offers a very powerful rendering of this sadness, evident in the stunning elementary clarity of these concluding lines:

Everything follows its course.

Nothing consults with me—

Not the last grain of sand, not even my blood.

I can only ask you to

Forgive me.

The enjambment allows “forgive me” to hover between surrender and persistence, as if its speaker is still somehow unwilling to give up the fight.

This combination of direct clarity and stunning, original figuration shapes virtually all of Blandiana’s subsequent work, even as she continues to explore how language can capably be a force of resistance. Upon moving into the 1970s and 80s, her work will locate this mystery primarily in dreams, suggesting a secret order to the universe. Increasingly, the poet finds such order in classical and local mythology, and the output of this time is greatly concerned with how poetry can re-animate the emotional core of what myths had once provided society.

In “Egg,” a piece from the 1981 collection The Cricket’s Eye, Blandiana creates a compelling entry into the imaginative space afforded by Platonic mythology, using images of unity to contrast against the painful features of everyday reality, and intensifying this emotive impact with simplistic language:

Do you remember how good

It was, enclosed forever in

The egg on the waters

Where the universe fits,

A single being, complete inside

And all self-sufficient

Light afloat on light?Do you remember how we floated there?

Love with no yearning

Only reflecting itself, speechless

And content, like a spring,

Pain hadn’t yet been invented,

Loneliness did not exist,

The world was not yet born.

By opening with a casual address, the poem immediately gives the mythic an intimate place in daily life, which in turn interprets and justifies the bareboned language. For Blandiana, myth is simple—an effort to understand our latent desires and capacities, a description of what it means to live in accord with values incompatible with modern life—which leads to its banishment to imaginary realms. It then becomes the poet’s task to restore those values by reminding us of what we’ve lost.

In the poem’s brief five stanzas, Blandiana introduces an original universe, depicting its purity and nothingness—no pain, no loneliness, no world. After detailing the profound unity of this reality, she turns to the universal second person, asking her readers to assess the separations that emerged when “The perfect egg was split in two / It broke into heaven and earth.” Anchoring this myth within the psyches of individual subjects, Blandiana then begins the fourth stanza on the most microscopic level, describing cells amidst the terror of separation, before expanding once again to cosmic detail:

The earth reached up into the trees

And the sky was tangled in branches

To cover the naked wound

Where they had broken in two.

The final stanza is retrospective, and Blandiana asks for a mode of memory that accounts for all that has been wasted while painting a potential end of the world where “. . . a perfect egg / Will be born, floating on the waters / In the silence of the beginning.” In this vision, we would encounter finality as a silence that promises to resist all of the divisions and the loneliness, inseparable from our awareness of our individual separations.

For Blandiana, such experiments of myth return her to a concern for the role of poets in facing the divisions of our world. Derrick and Patea stress Blandiana’s description of her poetry in the 80s as primarily a “hunt” for evocative mystery, to which she can surrender her ego: “I’ve never hunted for words / I’ve only searched for their long / Silver shadows / Drawn across the grass by the sun/ Pushed across the sea by the moon.”

This searching for shadows establishes the conditions for her brilliant career, of which the primary feature is a startling direct refusal of lyric rhetoric, combined with a startling and intimate structural organization. Emily Dickinson immediately comes to mind as a comparison—but George Herbert could also be a closer analogue. Such figures, as in “Egg,” achieve an astonishing inwardness, exemplifying her depiction of an imagination that wants as direct an access as possible to its own imperatives, seeking to appreciate its own needs and demands. One sees here the aim to recover, in the poet’s own fashion, the space traditionally occupied by mythology.

At times Blandiana is not completely successful, a phenomenon worth examining because the majority of the poems create effects that stand out by contrast—for example, when she ties her figures too explicitly to a first-person experience, resulting in the demands of the ego diminishing the potential universal force of the figure. Another concern that pertains to this collection directly is the question of whether or not it addresses a sufficient variety of social situations and the emotions embedded in them. This lack may be the price one pays for having primary ontological concerns that rarely vary, despite distinctive metaphoric structures. There is no doubt that Blandiana is a major contemporary poet—but such notes call into question her range, and therefore her capacity to be considered as one of the truly great European poets.

But in the many terrific poems that stand out in contrast to the problematic ones, they offer astonishing ways of capturing how language has broken through to our inner lives, in the way of Donne, Herbert, or Beaudelaire—poets who direct their words into the shadows of language. One of my favorite governing conceits of the collection occurs in the poem “Eclipse,” which rivals—in intensity and scope—and echoes Beaudelaire’s “The Albatross.” In its opening lines, Blandiana writes:

I give up pity like a vice. they’ve drugged me

with pity since I was old enough to speak.

doe-eyed, crown of stars, I weep silly tears

with the defeated, disinherited, the meek.

The following lines then show a remarkable shift in tone (which also gestures to the translators’ fine work) from the above generalized unhappiness to a sheer, powerful assertion, leading to the final two stanzas that emphasize the force of the emotional mind:

I open tender hands, to caress

wild beasts that hungrily creep near me.

It’s sad to think I’ll never kiss again

the snout that wants to tear me.

I’ve stifled myself, to avoid offending.

My knees have taken root in the ground

and my life has become a single wish:

oh let these wings grow nails to grip me down.

With a string of monosyllables presenting the relation between the simple wish and the ominous consequences of committing to an internal world—one beyond moral rhetoric—Blandiana claims a psychic prowess that afford us intense access to our desires. In this, the poet’s early work invites us precisely to inhabit a place where violence is projected toward comfortable states of self-consciousness, where every trace becomes a wound, and where memory is necessary or unavoidable because it remains incomplete. Pain is intensified here, as is isolation, violence, self-consciousness—but also acceptance, persistence, and liberation.

Charles Altieri taught English literature for fifty-two years, the last twenty-eight at UC Berkeley. He has written over ten academic books and over two hundred essays, with a new book, Imaginative Experience: Promoting the Liberal Arts, coming out from Bloomsbury this September.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: