In Ecuadoran writer Natalia García Freire’s latest novel, A Carnival of Atrocities, rising from the landscape is a swirling, multivocal, and vivid portrait of a small town torn apart by prejudices and suspicion. There may be something rotten buried deep in the earth—but perhaps it is history itself. With an expert, distinguished lyricism translated melodiously by Victor Meadowcroft, García Freire aims her incisive sights on the violence and hatred that pervade amidst dissenting belief systems, gesturing towards the ways a limited, desperate existence can further inhibit our shortsighted perspectives.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

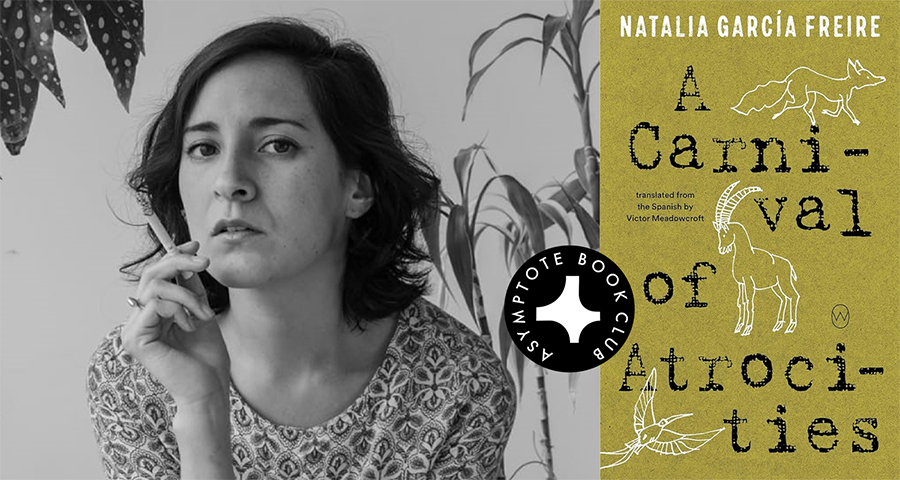

A Carnival of Atrocities by Natalia García Freire, translated from the Spanish by Victor Meadowcroft, World Editions, 2025

There is something about a fictional town that allows their inventors to bend the rules of everyday life—to infuse these imagined destinations with magic, tragedy, and often fear. In novels like Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude or Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo, the respective towns of Macondo and Comala have become canonical spaces to reflect on death, family, faith, tradition, and the world itself. Natalia García Freire’s A Carnival of Atrocities is no exception: in the fictional town of Cocuán, myth, brutality, and poetic cruelty intertwine.

Translated masterfully by Victor Meadowcroft, García Freire’s prose is visceral and magical, with an eerie fable-like quality that blends earthly violence with detritus and beauty. This haunting lyricism gradually builds the story around the ostracized Mildred Capa, a mysterious girl cursed with luminous sores, and details the collective violence that erupts as fear and superstition consume the community. Although the novel hosts multiple voices and narrations from the town’s inhabitants, it often feels that the true protagonist is Cocuán itself—a place so vividly rendered that it pulses with both life and decay:

We’re an old and vanished town. You must realize. Nothing in Cocuán is what it seems. We’re all composed of dust and evil, like nightmares. Our cemetery is a swamp sown with rotten crosses that disappear now every time the river swells. Not even our dead want to remain with us.

To the rest of the world, Cocuán is nearly invisible—a place to pass through—and the Capa family are one of the very few that arrive to stay. But for its inhabitants, the town is an all-consuming presence, a judgmental force. They move in hive-like cruelty, with the soil beneath them clinging to cycles of violence. As in so many small Latin American communities, Cocuán is a place of fractured identities, a battleground between Catholicism and local cosmologies: part devoted fervor, part Indigenous myth, part collective madness. In other words, Cocuán epitomizes religious syncretism, and it drives the narrative with equal measures of collective guilt and superstition.

Mildred Capa is both the spark and the specter at the heart of the novel, a cursed innocent whose persecution catalyzes Cocuán’s descent into madness. From the opening chapter, her body becomes a battleground: her luminous sores, described as “clusters and galaxies,” mark her as both divine and monstrous in the eyes of the town. She is then expelled from society, having come to embody the town’s repressed fears, but even after her confinement in a monastery, Mildred’s presence lingers as the Diosmadre, a mythic figure whose skinless body glows with unresolved mystery, and the novel orbits her absence. Each of its various stories is a ripple from the stone of her suffering: Ezequiel’s violence, Agustina’s visions, Manzi’s mutilation—all of it traces back to the girl who had “brought the wind.” In Cocuán’s collective nightmare, Mildred is both the wound and the knife.

It is precisely this polyphonic nature of A Carnival of Atrocities that converts Cocuán into an unsettling tapestry of myth and brutality. Like a dark chorus, its inhabitants take turns narrating their fragmented perspectives, unfurling a portrait of an unraveling community—but this narrative strategy does more than advance the plot; it embodies the novel’s themes of fractured identity, communal guilt, and multiplicitous truths. As opposed to Mildred, for example, whose narration feels both naive and sacred, Ezequiel’s chapter is actively brutal and violent. Whether he’s beating his brother Victor or murdering a fox pup, his voice is raw and unfiltered, often blurring the line between human and animal. Moreover, his savagery is fueled by paternal absence; while beating Victor, he recalls how his father used to hit their mother, demonstrating the genealogy of violence and the curse of Cocuán as something that persists through generations.

On another hand, the chapter of Agustina introduces a surreal, poetic register. Her stream-of-consciousness monologues blend folk wisdom with madness, acting as the town’s fevered subconscious. Where other characters repress Cocuán’s secrets, Agustina spews them in cryptic bursts, calling the landlord’s son a “lousy sad man” and revealing illicit affairs. Her chapter resembles incantation, full of non-sequiturs and abrupt shifts that mirror the town’s disintegration; here, it feels like García Freire is testing the limits of language and writing itself.

Although there are several other chapters, García Freire reserves her most daring narrative choice for Filatelio, the so-called town fool, whose words both conclude the novel and reframe it entirely. His broken, lyrical voice reveals what others deny: that Mildred was never just a girl, but the embodiment of both sin and salvation. Though he is dismissed as mad by others, it is his insight that ironically rings with the greatest clarity, tying the novel’s threads into a chilling conclusion.

A Carnival of Atrocity thereby creates a tremendous tapestry of humanity, but next to Cocuán, the other great protagonist is perhaps the forest and everything it represents. Standing in stark opposition with the town, its wildness exposes the corruption of human society:

A forest is a black hole, what it traps is never released, not even light can escape it. A forest is the stillness of God, the place where flowers climb and fall, a wind containing many winds, a snare in which the dead find themselves strung up like hares, wailing and screeching.

In contrast to the town that reeks of “stale drain water” and “cheap cologne,” the forest thrums with unchecked vitality. Smelling of “rain and fresh grass,” it had been a sanctuary where Mildred’s pigs had wallowed joyfully, where the waters rushed with carp that “hugg[ed] the curve of the riverbend.” Unlike the town’s rigid hierarchies, the forest operates by its own logic: horses gallop with preternatural purpose, and missing townsfolk shed their clothes to become luminous, almost mythic figures. Mildred had lived in a small house in the woods near the river, and after her abduction, the forest becomes a place from which the people of Cocuán never return. In the end, the novel suggests the town’s true atrocity was its denial of nature’s power—and its punishment is to be swallowed back into the wildness it feared.

Guiding us capably through the madness of Cocuán and its inhabitants is Meadowcraft’s admirable translation, which preserves the musicality and rhythm of the Spanish original. Notably, he retains certain Spanish words to enhance the novel’s locality, but is unafraid to make substantial changes to add to its richness. The title A Carnival of Atrocities is a departure from the original’s Trajiste contigo el viento (You Brought the Wind With You), but offers a distinct and equally potent lens into the narrative.

Reimagining gothic tradition through an Andean lens, García Freire’s work springs from the soil of rural Ecuador, where Catholic guilt collides with Indigenous cosmologies, and landscapes pulse with animistic menace. Throughout, A Carnival of Atrocities seethes with the unsettling truth that violence isn’t merely committed upon the land—it emanates from it. Cocuán’s soil is less a setting than an accomplice; its river carries the memory of baptisms and burnings, its forests swallow secrets only to spit them back as nightmares, and even the wind whispers of atrocities, buried like roots. The faith of Cocuán and of its inhabitants suggests that violence sown into the earth will always erupt anew, as inevitable as the sprouting of black-eyed Susans through the cracked adobe.

Through the thriving Latin American gothic movement, women authors have uniquely explored themes of fear, violence, death, nature, and tradition—and A Carnival of Atrocities resonates with works like Argentine writer Mariana Enríquez’s Our Share of Night, Mexican author Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season, and fellow Ecuadorian Mónica Ojeda’s The Flying Women. However, García Freire pushes the genre further, reinventing it as a sort of geography where dirt, rivers, and flesh are archives of pain and violence, and thhe arrival of this powerful novel will surely establish her as a vital voice in this developing canon.

René Esaú Sánchez (Guerrero, México. 1997). Journalist and translator. He writes about politics and culture weekly for the Mexican magazine Vértigo. He has translated Iris Murdoch into Spanish and Rosario Castellanos into English. He has also collaborated with publications such as Periódico de Poesía, Reflexiones Marginales, and the Trinity Journal of Literary Translation. Currently, he serves as an editor-at-large in México for Asymptote Journal and studies an MLitt in Comparative Literature at the University of St. Andrews.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: