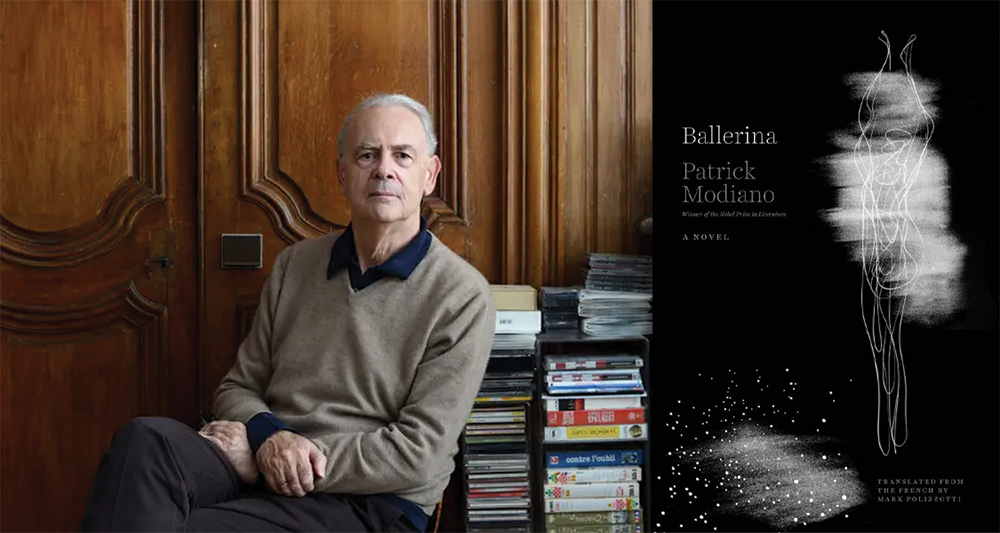

Ballerina by Patrick Modiano, translated from the French by Mark Polizzotti, Yale University Press, 2025

Patrick Modiano’s latest work, Ballerina, takes its readers to a Paris that feels uncertain, still marked by the shadow of the Second World War. Like most of the author’s other publications, so too is this novella written as autofiction, with the main perspective being that of the same young man who normally figures in his writing. Over the course of his story, we float from recollection to recollection, following the narrator’s attempts to capture the memories of his youth in 1960s Paris—during which he finds himself admitted into a ballerina’s circle.

Despite the title, the eponymous dancer herself feels less like a central figure than what we might be led to expect. She is, of course, present and recurring in the narrator’s focus, acting as the glue between him and the other characters, threading connections that are introduced over the course of the novella—but as we read through the story, we feel as though we are trying to catch hold of an ever-elusive spirit, rather than an actual person.

It is at this point that one comes to consider the metaphor of dancing and ballet, and how it further feeds into the ballerina’s enigmatic character. While the novella’s title bears her epithet (which is also her nickname), this is as much as we receive in terms of her identification. In contrast, every other figure, barring the narrator, is named: the ballerina’s son, Pierre; Hovine, whom the ballerina had known ‘since childhood’; Verzini, the narrator’s landlord and the ballerina’s friend; and Kniaseff, the ballet master, to name but a few. In this way, nearly all the characters are rendered concrete and tangible, not only through their names, but also the short physical descriptions which accompany them.

The ballerina, meanwhile, is a wisp, a billow of smoke to the reader. The novella’s opening line is the only depiction of her appearance, and even then it is rather mundane, though certainly evocative: ‘Brown? No. More like chestnut, with very dark eyes. She’s the only one of whom a photo might still exist.’ Although there is nothing immediately unique in her appearance, we intrinsically understand her striking nature and power over the narrator. It might seem ironic, then, that despite the inherent fascination the ballerina indisputably holds, we encounter no other material descriptors.

But perhaps this is the whole point. Instead of focusing on her looks, we often come across passages which light upon her other qualities—her movement, her aura, her personality. In describing the sight of her dancing, Modiano writes: ‘According to Kniaseff, the body first had to exhaust itself to reach a state of lightness and of fluidity of movement in the legs and arms.’ He then goes further, homing in on the details:

All her efforts to make herself lighter, all that work to “soften the elbows,” as Kniaseff said, and give her arms almost immaterial fluidity and fragility . . . Perhaps she would end up flying away, passing through the walls and ceilings and emerging into the fresh air of the boulevard.

The very aim of any movement or attitude in ballet is always to give the semblance of effortlessness and airiness, regardless of one’s extreme muscular exertion and fatigue. It is namely this core principle that Kniaseff evokes when he talks of achieving that ‘state of lightness.’ But in the narrator’s portrait of the ballerina’s ‘immaterial fluidity and fragility’—so intense that she might ‘end up flying away’—we can clearly see that her character, her very being, has taken on an undeniable evanescence. The ballerina is a spirit, floating, drifting. In the narrator’s eyes, she is free of the physical boundaries that fetter others.

Although the ballerina clearly belongs to the narrator’s memories, she is herself a living manifestation of memory, its transient and vaporous-like nature. Just as when we call memories to mind, the ballerina is always just out of reach for the narrator. Though he has ‘a hard time keeping up with her,’ he is still forever striving to reach her, to solidify the connection and the strong, silent bond which subsists between them.

Modiano’s work engages with literary traditions and themes innate to autofiction: identity, the passage of time, fragmented recollections. Indeed, we recognise the irrefutable influence of Proust’s writing, as well as notes of other writers who were similarly inspired. (Yuri Felsen and his novel, Deceit, (also set in Paris) come to mind.) Ballerina engages and reproduces these classical themes, but consistently weaves in musical and ballet imagery to highlight the interplay between music, dance, and memory: ‘I have only a disjointed memory of that evening, as if it had unfolded on a staccato rhythm, faster and faster.’

Translator Mark Polizotti, who previously brought us Scholastique Mukasonga’s Kibogo, spectacularly captures Modiano’s style and tone, which sets itself apart in its preservation of a consistently lyrical, highly evocative mode, flowing despite the excessively long sentences which occasionally run the risk of losing the reader. Despite the potential difficulties in preserving the rhythm in a language whose natural scansion is remarkably different from French, Polizotti’s rendering reads just as light and airy and evocative as Modiano’s original. In a work like Ballerina, where so much of the world-building and story is heavily reliant on the language’s pace—especially in considering the key role that music and dance plays—the reproduction of similarly impressionistic images is no small feat.

It should also be noted that the musicality of each sentence in Ballerina is incontrovertible—and the melody of Polizzotti’s translation does not suffer in any way. When we read a line like ‘Day after day, it felt like I was drifting in the streets and that there was no difference between me and those sidewalks, those lights, to the point of becoming invisible,’ at no point do we feel trapped behind the veil of the language barrier. The subtle alliteration and assonance in the English feel no different to the operative techniques in Modiano’s original: ‘Jour après jour, j’avais l’impression de flotter dans les rues et de ne pas pouvoir me distinguer de ces trottoirs et de ces lumières, au point de devenir invisible.’ Whether it is in this effortless extract capturing the essence of the flâneur, or at any other given point, Polizzotti’s translation retains the same slightly melancholic and musical air which Modiano employs.

This short novella is like a breath of fresh air, keeping one’s company for a fleeting moment, revitalising the stale with new perspectives and considerations, then flitting on, curling upwards and away. We are left with the indelible impression of an unpretentious, thought-provoking work that, much like Ballerina’s narrator, offers us the opportunity to contemplate the ‘eternal present’ of our memories.

Sophie Benbelaid holds two degrees in French and Russian Literature from the University of Oxford. She is an aspiring literary translator, and hopes to publish her work in the near future.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: