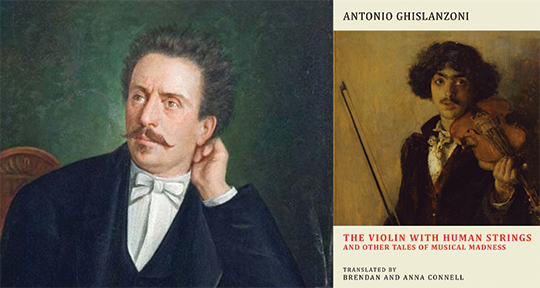

The Violin with Human Strings and Other Tales of Musical Madness by Antonio Ghislanzoni, translated from the Italian by Brendan and Anna Connell, Snuggly Books, 2024

Bach, Liszt, Paganini, Beethoven. . . these virtuosos have been immortalized in western societies—but what about the supremely talented musicians who clawed their path toward the zenith, only to ultimately fall short? In The Violin with Human Strings: And Other Tales of Musical Madness, written in Italian by Antonio Ghislanzoni and translated by Brendan and Anna Connell, the author paints the journey of four such less fortunate individuals. Throughout the collection, a recurring motif seems to ask: Is musical renown attained via wits and ambition, or via preternatural gift? Whatever the answer to the perennial debate on nature versus nurture in musical talent, the four stories here testify that a destructive impulse for mastery will eventually lead to madness.

A contemporary of revolutionaries such as Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi, Antonio Ghislanzoni (1824-1893) was a multi-talented Lombard who began his career as a musician (principally as a vocalist), but turned to devote the latter half of his life to writing, resulting in a prolific corpus of articles, novels, short stories, and some eighty librettos. He was also an important member of the Scapigliatura movement, a loose-knit group of artists in Milan who gathered after the 1860 Unification of Italy. An Italian counterpart to the French Bohèmi, the group idealized patriotism, anti-conformism, and intellectual independence, with its writers being receptive to international writers such as Mary Shelley and Edgar Allen Poe—an influence that shows in Ghislanzoni’s fiction.

Save for opera aficionados, however, most Anglophone readers will not recognize the author’s name; type “Ghislanzoni” into a search bar, and results on Verdi’s Aida will populate the list. Still, considering the writer’s accomplishments, it is a surprise that the English translation of his prose has not been published in book form until now.

The four short stories in The Violin with Human Strings are fast-paced and plot-driven, combining elements of satire, black comedy, and the fantastic, yet the real value of this collection is its aptly drawn portrait of the music world in nineteenth-century Europe, a milieu so cynical and caustic it accelerates the downfall of our protagonists. It is as if this work of fiction serves as a testament to “the novel as a primary source”; in its words, the readers breathe in the air of the epoch. Having himself hobnobbed with the musicians, Ghislanzoni is well-versed in the scene, and the protagonists featured here—a violinist, a pianist, a trumpeter, and a vocalist—are shown with realistic definition, endeavoring to scale over the wall of destiny and attain that musical singularity, whatever the cost.

The titular first story is about a German violinist by the name of Franz Sthoeny, who challenges Niccolò Paganini—that infamous archetype of demonic performance—to a duel. Ridden with illuminating descriptions of musical performance, the story paints Paganini in action: “Never before had the Italian artist . . . revealed such diabolical power. The strings of the violin, beneath the pressure of his lean fingers, contorted themselves like palpitating entrails—the satanic eyes of the violinist evoked hell from the mysterious cavities of his instruments.” Sthoeny, a very competent musician himself, is forced to recognize at once the insurmountable superiority of Paganini’s talent, but his teacher reveals that not only has Paganini sold his soul to the devil in exchange for musical talent, he also uses human fibers as his violin strings. These facts propel them to concoct a grotesque plan, after which Sthoeny confronts the maestro with an instrument equipped with the entrails of his teacher. Regardless of these efforts, the duel ends with Paganini’s gleeful victory, upon which he advises the inconsolable Sthoney with a revelation that hints at national fervor and ethnic pride, prevalent in Italy after the chaos of its unification.

The second story in the collection, titled “Daniel Nabaäm De-Schudmoëken,” further elucidates the sticky alliance between national identity and musical superiority. It begins in an artistic salon run by a countess who “although extremely Italian in the political sense, professed herself to be German when it came to art.” During one of the salon’s sessions, the eponymous pianist is warmly welcomed by the audience, among which sits our narrator—a journalist who begins to probe his own memory, for he remembers the pianist’s face but not the name. His confusion then leads to the truth that the pianist had in fact once lived by a different, glaringly Italian name: Bartolomeo Scannagatta (explained in a footnote as roughly translating to “cat-butcher”). Later, the pianist, who now goes by the prominently German moniker, recounts to his father the toils and tribulations of his apprenticeship years, bemoaning the “baleful influence” of his name on his musical career.

The fact of a performer’s name is a catalyst for Ghislanzoni to describe an audience full of prejudices and nonsense, as Scannagatta/De-Schudmoëken justifies his change: “Can you not perhaps hear, in the solemn and almost patriarchal sound of the name, the majestic, sedate pianist who proceeds confidently over melodic waves, like a mighty ship, already tested by tempests and winds? Liszt! . . .Don’t you see, in this name, the lightning and thunderbolts flashing from the keys?” The father is unconvinced, as he believes his son should honor their familial pedigree, but maybe there is a point to the pianist’s argument. Certain names of the twentieth century maestros, such Leonard Bernstein and Herbert von Karajan, are unmistakably regal, distinctive, and, yes, mouthful in their syllables. This story exemplifies the adoption of nom de guerre, a marketing gimmick still very much in use today in the world of music.

In the third story, “Rubly’s Trumpet,” music, love, and death form a holy trinity. The protagonists are Paolo Rubly and his frail wife Maria, who suffers from tuberculosis, and Ghislanzoni establishes her quickly approaching death early on: “Love is the religion of the heart; and it is necessary that it should have its own martyrs.” Paolo plays trumpet in an orchestra and his wife accompanies him on the tour, but when Maria’s condition worsens, they retreat to the countryside—an effort that does nothing to change her fate.

Paolo is a superb trumpeter known for soul-shattering playing, and his wife’s death endows him with emotions that manifest in his performance. As the director of the orchestra praises: “When God needs a trumpet to summon the dead from their graves and call them to the final judgement, He can do no better than to entrust the solemn mission to you.” Paolo receives this outburst at face value and dares himself to a Frankensteinian mission.

The last story in the collection, “Autobiography of an Ex-Vocalist,” is about a hapless singer called “Pirletta” (which the footnote describes as being derived from the word “piroetta,” meaning pirouette). As a young man in the rural village, he helps his father with breeding maggots and manufacturing cheese, but one day, the village organist hears him singing litanies in church and deems him a tenor with a voice of great beauty. Count and Countess Bavoso of the region then commission his music education, enrolling him in the Conservatory in Milan. The whole village expects him to be a millionaire in ten years.

Naturally, things do not turn out as expected. The city of Milan is full of teachers ready to prey on country lads with bloated dreams. The most famous singing teachers are quacks who implement on their students “the grand principle of respiration,” which is nothing but a phony experiment that ruins Pirletta’s lung capacity. The singer’s teeth are pulled since “they had caused middle notes to be a bit dull.” His gigs are scarce and limited to demeaning roles: “. . . the theatrical agents were a mob of murderers, the public a crowd of imbeciles, and the best paid artists a camorra of schemers without either voice or talent.” Eventually, he comes home a broken man. The reader sees in Pirletta’s challenges a mirror of those confronted by twenty-first century musicians, who are often exploited if on quite different terms; the majority earn a pittance, while streaming services such as Apple Music and Spotify scoop in millions.

Although written more than one hundred and fifty years ago, these stories come to us fluidly thanks to the clear and accessible translation rendered by the Connells. Some cultural-specific vocabularies pepper the prose here and there, leaving an Italian aura, and a plentiful array of footnotes serve to enlighten the reader on the prominent musical events or musicians of the day. The Violin with Human Strings is thus perfect for anyone partial to fiction relating to musical grandiosity and its drama, reminiscent of Thomas Bernhard’s The Loser or Thomas Mann’s The Doctor Faustus. These prominent writers too associate musical artistry with mania and madness, as if its very pursuit is the devil’s business.

The grandeur of music, granting us beauty and sublimity, truly does seem immune to the passing of time, as if it is rendered and protected by some immortal entity. However, all such works—Beethoven’s Symphonies, Liszt’s Transcendental Études—have been formed by human tendencies at their extreme: love and ambition, malice and murderous rivalry. This emotional intensity is what continues to transport and bedazzle listeners, and in literature, we are given an understanding into what it takes to create such works through the sight of characters standing on the edge of some precipice, ready to take a Kierkegaardian leap. Ghislanzoni’s fiction opens up this view.

Richard M. Cho is a librarian for humanities and literature at a public university in California.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: