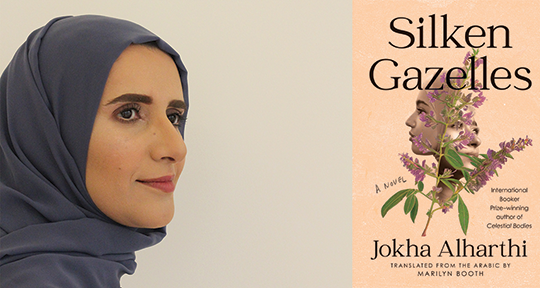

Silken Gazelles by Jokha Alharthi, translated from the Arabic by Marilyn Booth, Catapult, 2024

The acclaimed Omani writer and academic Jokha Alharthi has emerged as an increasingly significant voice on the international literary landscape since her novel, Celestial Bodies (translated by Marilyn Booth), was awarded the International Booker Prize in 2019. Now, once again, Catapult Press has opened the floodgates to another tentacle of the Omani society in the form of Alharthi’s fragmented worlds. In her latest novel Silken Gazelles, also gracefully translated by Booth, a wide net reins in the past to the present, the village to the city, sisterhood to motherhood, and love to loss. The dreamy and nonlinear narrative moves forward and backward in time, treating generations as flexible containers and relying on polyphony to create a poetic geometry of voices.

Tellingly, the intertwined threads of the narrative are captivating from the very beginning; extremely concise hints are made in the early chapters towards the throughline, but the hints are almost complete in themselves. At the end of the first chapter, for instance, Ghazaala’s life is wrapped up in a few sentences. “Within five years [she] had given birth to twins,” writes Alharthi, “finished her secondary education, and entered the university. In her final year of study in the College of Economics, the Violin Player ran away from the house of marriage.” In a similar vein, in the second chapter, when talking about Ghazaala’s foster mother, Saada, Alharthi writes:

It would have seemed so ordinary, so natural, for Saada to live to be a hundred years old. For Saada to always be there, preparing maghbara for the cow and coconut sweets for the children, drawing milk and cream, feeding Ghazaala and Asiya and Mahbuba and the goats, undoing her hair and baking as she sang, exuding a fragrance of incense and fresh dough, laughing her ringing laugh, and forever gathering the plants that could treat poisons and fevers from the high slopes surrounding Sharaat Bat. . . But Saada never made it, not even to thirty.

Despite the elegant self-containment of these life-threads, one cannot help but savor the prose, which subtly poses a fundamental question of life: whether one should accept things as they are, or burn everything down out of fear.

The book opens with a shocking scene: a mother, after learning of her father’s sudden death amidst the wailing of her neighbors, unconsciously tosses away her newborn baby girl. This infant, her wrappings half undone, would later become the central figure of the novel, and it is her memories that go on to drive the narrative. The girl eventually finds herself with two mothers—one biological, Fathiya, and one a foster parent, Saada, who snatches the screaming baby and breastfeeds her. The memory of Fathiya inevitably fades away, not only in the chapters of the novel but also in Ghazaala’s life, rendering any impressions vague: “She always believed that her own mother must really be named Saada. And the woman whom everyone called Saada must actually be Fathiya. She did not know how to explain any of this mix-up, but she did believe that a serious mistake had been made that had caused all of the names to end up with the wrong people.”

The circle of bewilderment widens. Saada names her “Ghazaala,” but when Fathiya later returns to her senses and has the baby brought to her, she records the child as “Layla” on the birth certificate. Everyone, however, continues to call her Ghazaala. Thus she grows older, bearing two names.

Saada remains the true and closest mother, and a close relationship additionally forms between Ghazaala and Asiya, Saada’s daughter, who becomes her milk-sister. With the arena of family somewhat settled, Ghazaala continues to search for romantic love throughout her life, and at sixteen, she falls for her neighbor—the Violin Player—and marries him. However, the flames are soon extinguished when he abandons her after she gives birth to twins, thereby turning Ghazaala into a single mother at the beginning of her university years. In her new world, filled with the challenges of motherhood, study, and work, Ghazaala clings to the memories of her childhood, notably featuring her milk-sister Asiya, and these recollections continue to seep throughout the pages like distant flashes of light. In effect, Alharthi uses them to depict the serene life of a simple Omani village, where Ghazaala and Asiya had played in plains, swam in small water channels (or aflaj), milked the cow Mahbuba, and played with the cat Shaybub. Sadly, tragic circumstances had led Asiya’s family to abandon the village, leaving Ghazaala alone—the deep impression and tragic end to this friendship will go on to shadow all the relationships that follow in Ghazaala’s life.

With the disappearance of several characters—who nevertheless remain like ghosts, haunting Ghazaala in her everyday struggles—the presence of a new friend, Harir, comes as a jolt. Harir’s journal entries form the backbone of the narrative, chronicling experiences ranging from that of university life, to accompanying her mother on a chemotherapy treatment in Bangkok. They also offer a glimpse into the complex social and intellectual lives of young women, exposing their internal contradictions. Salaayim, “the greatest gossip” in the university housing, acts as an all-knowing portal to the drama of campus life, sharing the news about the second-year student who eloped “with a male student from the same year, only to be nabbed by the police as they were returning through the main gate”; or tales of “the young women in the College of Arts who punctured the tires” of their modern criticism professor’s car; and “the father who came to the residence hall and dragged his daughter out by her hair” in a public spectacle. Even faculty members aren’t immune to scandal, as evidenced by the business school professor “who married his master’s student when he already had a wife.”

Through interconnected stories, Alharthi masterfully weaves a network of characters in a narrative inhabited by lively, magnificent women. No one is like the other; each has a unique story to be told, whether they’re major characters like Ghazaala, Asiya, Saada, Harir, Maliha, or minor characters with a stinging effect like Fathiya, Afraa, Salaayim, Sarira, and Iffat. Silken Gazelles is a portrait of all of them, struggling to carve their own spaces for existence and survival.

Ghazaala, who knows the difficulties of motherhood and belonging, never finds a solid ground to contain her confused emotions. Her escape from her family home is merely a temporary refuge, and when the first object of her affections goes on to leave her, she searches for another source of comfort, coming across a sweet-talking man known only as the Singer to the Queen. When that relationship too dissipates, she ends up with the Elephant. These lovers are deeply symbolic figures, as Ghazaala continues to follow in the footsteps of people who play with her emotions, much like the violinist playing the strings. Though these narrative turns could be read as a reflection of her fragility, she instead defies that characterization as the most determined of Alharthi’s female characters. She keeps pushing “her world in front of her like a huge and heavy chest without wheels.”

None of the women of Silken Gazelles are able to be self-sufficient except for Harir, who has enjoyed a luxurious life with an ambassador father and a mother who does not invoke any marked traumas. On the contrary, her mother is almost invisible. Harir has her own mysterious world in her large house overlooking the sea, between an indifferent mother, a strict grandmother, and a distant father—whose influence is almost negligible, only appearing on the birth certificate. She goes on to marry a well-qualified man, but ends up as lost as her mother in her married life and motherhood. Still, the strong and emotionally complex voice of her diaries contradicts the stereotypical image of wives and mothers, and she eventually finds some form of liberation in returning to her childhood dream of horse-riding.

Silken Gazelles is characterized by the abundance of characters isolated in their own environment. Fluctuating between the past and the present, mothers and daughters are stumbling with seemingly similar struggles, as if their fate is to inherit the sufferings of those who preceded them, even if circumstances, and places differ. Each of them carried on her back “the gifts that [their] ancestors gave,” Mothers, here, do not pass down any recipe for strength; rather, the daughters inherit the fragility of their mothers’ souls, their weakness in the face of life’s brutality. Such women, despite the relentless harshness of reality, are also portraited as choosing the most arduous paths throughout the days—as if to punish themselves—and through these pains, one bears witness to them becoming strong, enlivened, resolutely challenging the calamities of time. They may find themselves in relationships with male characters, but these are simply transit stations—bridges to their true selves.

The reading experience of Silken Gazelles is to travel within time that has been expanded, a widening that makes room for liberal traversals between childhood, university life, and motherhood. While giving a clear vision of the contemporary, Alharthi also gives us transcendent moments of transportation to the fictionalized Omani village Sharaat Bat, opening a window onto the childhoods of Ghazaala and Asiya, as well the lives of their female ancestors. Marilyn Booth’s top-notch translation enthralls the reader with beautiful, cutting prose, letting the novel come alive with its many tales, its several generations strewn across the pages. Still, as with all novels that call attention to the discursions and decisions that make up a life, at its heart are its most compelling, complex figures: Ghazaala and Harir.

Ibrahim Fawzy is an MFA student at Boston University. He’s a two-time graduate of the British Center for Literary Translation (BCLT) Summer School. He was awarded a mentorship with the National Center for Writing, UK (2022/2023) as a part of their Emerging Literary Translators Program. He was also a recipient of Culture Resource’s Wijhat grant. He’s an editor at Rowayat, Asymptote, and Minor Literatures, and podcasts at New Book Network (NBN). Ibrahim won a 2023 PEN Presents award for his Arabic to English translation of Kuwaiti author Khalid Al Nasrallah’s The White Line of Night.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: