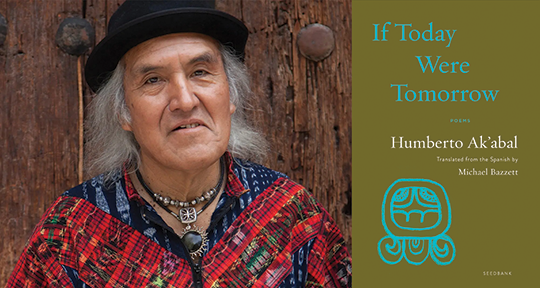

If Today Were Tomorrow by Humberto Ak’abal, translated from the K’iche’ and Spanish by Michael Bazzett, Milkweed Press, 2024

To read Humberto Ak’abal is to be transported: first to the Western Highlands of Guatemala, full of mountainous forests and ravines where corn grows amid the mist, and then through the natural world and toward everything it encompasses—the elements, their sounds, and even their language. In a world where the sun eats the mist, butterflies kiss the earth, and peach trees weep, the boundaries of the conscious world expand to envision a new, shared world.

Humberto Ak’abal was a K’iche’ Maya poet from Guatemala. His book Guardián de la caída de agua (Guardian of the Waterfall) was named Book of the Year by the Association of Guatemalan Journalists, and he was awarded the Golden Quetzal award in 1993. A world-renowned Guatemalan poet, Ak’abal oscillated between writing in K’iche’—his mother tongue—and Spanish, the official language of Guatemala. This new collection, published by Milkweed Press in June, spans five sections, each delving into a different facet of the poet’s oeuvre, while always retaining his essence, humor, and care for the natural world.

The five sections traverse first through the natural world, where the reader is invited to envision the inanimate as a part of ourselves in similar ways as the indigenous cosmovision does; the personal, seeing Ak’abal himself as he relates to a world, his relationships, and his love for both others and the land he inhabits; then the injustices faced by Indigenous communities in Guatemala as the natural world becomes a testament to their suffering; and finally towards a larger, more philosophical concept of Ak’abal, his ancestors, and the myriad ‘ifs’ that concern both the past and the present. Although the tone shifts throughout the expansive take on the poet’s work—from philosophical and imaginative, to serious and pained, to witty at times—the poet’s essence is palpable to the very last page. Through inventive and often humorous imagery, precise language, and thoughtful translations, Ak’abal and Bazzett dissolve humanity’s constructed boundaries to unite the natural world, languages, history, land, and even the poet himself, envisioning multifaceted perspectives on our relationship with our surroundings.

The animacy of the natural world is clear from the very first poem, as Ak’abal sits “at the foot of a cypress/chatting with the fog,” and continues throughout, as the moon becomes not just an orbital object but rather an eye that observes; the sun an entity that can be saddened by what it lights with its rays; the river a being that stays as water leaves. The endearing tone with which he refers to the natural world, paired with surrealist imagery, leads us to ponder lives and beings that could otherwise go unnoticed: if everything could have language, what would the birds say when they sing? What would the dogs think? What do they think, those who we believe don’t think at all? When the natural and animal worlds become conscious and thoughtful, aware and playful, readers can rejoice in the endless possibilities as humans, as they are also forced to think of their finite lives and roles in an interconnected world.

In “Leaves,” for example, a poem in the first part of the collection, Ak’abal writes: “Fallen leaves do not remember which tree they came from/or even that they were leaves.” If leaves shed their identities, could we? If they are naturally inclined to a world where they will all fall from their trees, does it matter what tree they belong to? Or the reason they fell? By bringing his readers closer to the natural world, Ak’abal also brings them closer to themselves. Plus, he brings them closer to his indigenous cosmovision, which encourages a symbiotic and trusting relationship between the natural and the human world. This, too, is shown in “Lighting”:

From time to time

the sky gets scared

of all that darkAnd launches lighting bolts

to see if we

are still down hereTo its surprise,

here we are,

trusting

the sky

is still up there

Part of what makes this world come alive is Ak’abal’s visual imagery, which Bazzett captures with precision. In Ak’abal’s world, actions and language traditionally associated with humanness describe the natural world, but the opposite is also true. In “My Wings,” for example, Ak’abal was “flapping my wings/and looking at the sky,” and then “waiting for the moment to leap into flight,” creating a blend of bird-like qualities with his body, which a few pages before was sitting atop of a mountain as a human. Colors, too, become not only a visual descriptor but lively entities with personalities that inhabit an entirely new social construct in which joy can be green but green can also sing. The creative exercise would’ve been enough to call this a wondrous work of art, but Ak’abal’s poetry expands beyond that; it’s a testament to the merging of beauty and pain, to the gain and the loss of inhabiting and sharing this world.

Translating Ak’abal, then, undoubtedly meant a balancing act as the meaning of the words was just as important as the sense of place, the sounds, and the imagery that the poet was conveying. Bazzett, a prolific translator and poet himself, was aware of the careful dance required for an effective rendition of what he calls “the song beneath the poems.”

Keeping certain words in their original Spanish or K’iche’, for example, allows Bazzett to preserve the sense of place and wonder that are crucial in Ak’abal’s poetry. Specific names of birds—like güegüecho and azacuanes—are kept in Spanish, bringing readers an inch closer to the mountains of Central America where the words were born. The words are important sonically, but also visually and conceptually, as the umlauts bring attention to themselves on a page filled with a language in which the diacritical mark is sparse. This bridge that Bazzett creates is also a part of the imbrication of worlds of this collection, in this case, languages that lay one on top of the other, working together as one.

In his translator’s note, Bazzett writes that part of his vision for the work was hearing the poems’ “songs” and capturing their music. Emphasizing the sounds and rhythms of language keeps with the singing tradition that is important in the K’iche’, where there is no literal translation for poet and instead, there is only singer. On certain occasions, then, Bazzett prioritizes maintaining the rhythm and sound of a verse instead of its literal meaning, creating a wonderful sonic experience for the English reader. For example:

He chops limbs,

gathers kindling,

heaps piles of firewood.Hack after hack: the sharp

scent of sap.

As a translator myself, I understand the complex balancing act of sacrifices when it comes to languages. It’s not just words that are moving from one language to the other, and it’s not even ideas, worldviews, and cultures that are hard to capture; it’s the entire construction of a language and therefore the construction of the self which becomes difficult to render. For example, I often felt pronouns in Bazzett’s translation felt repetitive, such as in one of the first poems of the collection, “Today”:

Today I woke up outside of me

and went out to find myself.I travelled roads and paths

until I found me.

The double repetition of me and the reflexive pronoun felt unvaried. However, understanding the challenge that Bazzett was up against helps us view his translation as a balancing act done with impeccable craftsmanship. In Spanish, a sentence can be constructed without a pronoun, since the verb in a sentence will also indicate the subject—which is how that poem reads in Spanish:

Hoy amanecí fuera de mí

Y salí a buscarmeRecorrí caminos y veredas

Hasta que me hallé

This is what creates the challenge of repetition. Bazzett, however, triangulated from all three languages, keeping us closer to the original K’iche’ and further from it at the same time, adding words but mirroring the sacrifices Ak’abal was constantly forced to make as he moved from his native language to Spanish, a language he said “was bought with the blood of his ancestors.” These gaps in language alternatives worked in Bazzett’s favor in other poems. For example, in “The Sad One”, the exclamation—¡Ay, de los alegres!—turns into a playful yet precise question: But those poor happy folks? The extra word poor is added in exchange for the sarcastic tone the phrase in Spanish carried.

Towards the end of the collection, as the world gets larger and the images more sociopolitical, we begin to see how little individuality matters in a world where everything and everyone is interrelated. As the poems get deeper into Guatemala’s social fabric, the silence on the page speaks for itself. In fact, in a recent interview with Asymptote, Bazzett said that “Ak’abal’s poetry lives in the silences around the work, in the emptiness of the page, like the hollow of a bell. Silence is one of the tools he employs in saying the unsayable.” This is most true in “And Nobody Sees Us”:

The flame of our blood

keeps burning

despite centuries of wind.We’re silenced

throats choked with song,

soulful misery,

our sadness coralled.And I want to break out screaming!

The lands they leave for us,

are mountain slopes,

pitched hillsides

that downpours wash away

little by little

into the bottomlands

that are no longer ours.Here we are,

standing along the roadside,

our gaze broken by tears……and nobody sees us.

The last verse of this poem sits amid the silence of a white page, letting its weight sink into the mind of the reader. Ak’abal and Bazzett’s carefully chosen words are also a way of filtering what to leave out. Through those delicate choices, they leave it up to the reader to understand. As the silence hangs, waiting for us to react, I can’t help but see the English-language poems drifting into the wind towards evermore readers who will, hopefully, begin to see. Within the imbrication of every facet of Ak’abal’s work, translated so thoughtfully by Bazzett, there is music. Every being has a song if we stay quiet enough to hear it. Since I read them, these songs have been singing in my mind.

Miranda Mazariegos is a Guatemalan journalist, writer, and translator. She began her career at NPR, contributing to programs such as Radio Ambulante, Consider This, Throughline, and All Things Considered. Her work explores the culture, history, and politics of Latin America. She is an MFA candidate at Columbia University, where she’s working on a collection of essays and teaching through the Undergraduate Writing Program.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: