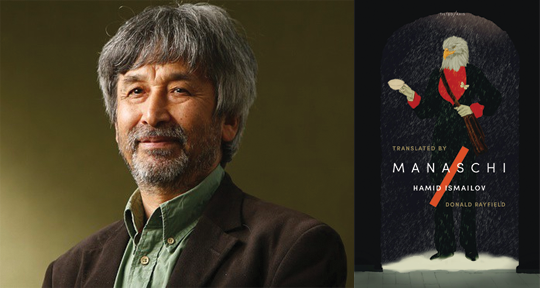

Manaschi by Hamid Ismailov, translated from the Uzbek by Donald Rayfield, Tilted Axis, 2021

Despite being home to incredibly rich and ancient traditions of both spoken and written word, little of Central Asian literatures is known to English-language readers. Such is what is being spectacularly rectified in Hamid Ismailov’s latest novel to appear in English—Manaschi. The text, artfully translated from Uzbek to English by the meticulous Donald Rayfield, is an ode to the deeply rooted tradition of storytelling that crosses boundaries of ethnicity, gender, age, and time, taking truly epic proportions in Ismailov’s riveting prose.

A manaschi, in Kyrgyz tradition, is the person—usually a man, young or old—who performs the recitation of the epic poetry Manas, a body of narratives that contains up to 900,000 verses, and transmitted only orally before given a written form in the late nineteenth century. Reciting the Manas is an act of shamanism; it involves phenomenal memory, years of training, musical talent, and inspiration kin to a trance state. For some, the act even enables in the performer the ability to interpret dreams or foretell the future. Learning and performing the Manas embodies a lifetime’s dedication to one of the longest oral texts known to humanity, and the sacred practice prevails to this day, as new generations—now including women—continue to be trained.

The story takes place on the contemporary Kyrgyz-Tajik border in Chekbel, a mountainous village inhabited by mixed populations of nomadic Kyrgyz and sedentary Tajiks. Bekesh, the main character, is a radio journalist who lives in an urban part of Kyrgyzstan. Upon receiving the news that his uncle Baisal—a reputed manaschi—has died, he returns to his ancestral village to attend the funeral. This visit, initially conceived as a temporary break from his modern routine, turns into a life-changing experience, opening formidable questions regarding his familial and cultural duties, his unequivocal choices on identity, and his moral responsibilities to his call as a manaschi.

Bekesh, being of mixed Kyrgyz and Tajik ancestry, references both cultures in daily life—quoting both from the Manas and the Sufi tradition of Islam, as well as from great Persianate poets such as Rumi. His views on multiculturalism and tolerance for Islam are not shared by all in the village—particularly after a group of Chinese workers is brought in to dig a tunnel. In a cross-cultural clash, supporters of radical Islam destroy the social harmony in the community, and the village becomes the locus of state-armed intervention, strictly enforced border controls, and an escalation of violence, leading to the kidnapping of some of the Chinese workers. These events can be seen to mirror real-life conflicts, as apparent in the most recent news on certain sections of the Kyrgyz-Tajik border.

But the border, in Ismailov’s prose, is more than a political reality. It serves as a trope to challenge some of the traditional notions around Central Asian identities, which often rely on simplistic oppositions: nomadic/sedentary, Turkic/Persianate, urban/rural. When I contacted the author to speak to him about this work, he explained to me: “People act as if identity was a thing fixed once and for ever, yet it is fluid and changes over time. The Turkic-speaking Uzbeks have been sedentary for the past five centuries, just like the Tajiks. Language or lifestyle is not enough to define identity, and we should not consider such markers as absolutes. The Soviet period from the 1920s to the 1990s brought opera, ballet, pop music, which are also part of the identity today. What interests me is what changes identity, and how we can apply centuries of our cultural heritage, such as the Manas or Rumi, to the new times.”

Engaging with the Manas is not an innocent or easy act, as Baisan, the deceased manaschi, once revealed to Beshek:

Reciting the Manas is like setting off on a very narrow track in the mountains. It is very hard to cross the slope, the path is so narrow and runs along an abyss, there are forty ravines all round! I’ve seen a great number of those who fell. The Manas turned out to be a burden to them. A lot of people proceeded by thinking that the Manas is about galloping horses and battles. The Manas is like water flowing at an angle. The very word Manas means human significance.

While Central Asia is often portrayed as a male-dominated society, gender roles are much more balanced than they might appear on the surface, something that is exemplified in the novel, and further detailed by Ismailov: “There is no gender in Turkic languages, maybe that comes from the nomadic past, as there is no distinction when you are on a horse, man, or woman. In Central Asia, the people transmitting stories are mostly women—who also happen to be the agents of changes in multiple revolutions, from the Soviet times to more recent periods.” In a dramatic episode in the novel, a group of women overtake a school-turned-prison and succeed in liberating their sons and husbands, a story that rings particularly true in light of the many street revolutions that have swept modern Kyrgyzstan.

Another refreshing aspect of the novel is Ismailov’s conscious choice to write first and foremost for a Central Asian audience, applying and multiplying proverbs which act as wonderful comments or asides of ironic wisdom—perfectly natural in the local cultural context. Ismailov acknowledges that this created almost insurmountable obstacles for his translator; not only do proverbs refer to specific aspects of Central Asian culture, but modern English prose does not make wide use of them.

Still, the most innovative aspect of Ismailov’s work is perhaps its take on the power of language, The author resonates with twentieth century modernist writers and theorists of language when he says:

Language is not a passive thing, it is a force just like atomic energy: once released it can be very destructive and have tragic consequences. I chose the Manas as a metaphor of the divine and the human, the intersection of two lines: the vertical one espoused by sedentary people who believe in one God, and the horizontal one represented by nomads who care more about man-to-man relations. Manas is a hero similar to those from Greek mythology.

In another telling passage, Ismailov writes: “It wasn’t the people following the Manas in their everyday lives; on the contrary, it was the epic itself running and guiding their destinies, dictating one thing, forbidding another.” In speaking to an ancient reverence for text, and its ability to work its way into our lives, Manaschi is a powerful book that lies at the nexus between the individual and the culture they are born into, of the mystic abilities to change, and be changed in return.

Filip Noubel was born in a Czech-French family and raised in Tashkent and Athens. He later studied Slavonic and East Asian languages in Tokyo, Paris, Prague, and Beijing. He has worked as a journalist and media trainer in Central Asia, Nepal, China, and Taiwan, and is now managing editor for Global Voices Online. He is also a literary translator, interviewer, Editor-at-Large for Central Asia for Asymptote, and guest editor for Beijing’s DanDu magazine. His translations from Chinese, Czech, Russian, and Uzbek have appeared in various magazines, and include the works of Yevgeny Abdullayev, Radka Denemarková, Jiří Hájíček, Huang Chong-kai, Hamid Ismailov, Martin Ryšavý, Tsering Woeser, Guzel Yakhina, and David Zábranský amongst others.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: