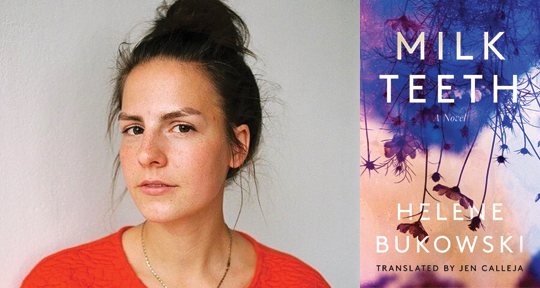

Milk Teeth by Helene Bukowski, translated from the German by Jen Calleja, Unnamed Press, 2021

You can’t expect the world to be exactly the same as it is in books.

Milk Teeth is claustrophobic. The silent world of Skalde and her mother Edith is cut off from everything else by fog and a collapsed bridge; civilization has also crumbled, and they reside in its remnants on the edge of a small, loosely-knit group in a so-called ‘territory.’ Edith has arrived in this place as an outsider, so though they are treated with tolerance, still disdain and suspicion dominate their relationships with most of the few people they have any contact with. In this fearful landscape, Skalde loses herself in books—until the day she starts losing her milk teeth, and finds a girl in the forest called Meisis. Thereafter, she slowly finds the strength to rebel against her mother’s neglect, and to question the rules of the society she finds herself in.

As a child, Skalde rarely leaves her house and garden, bringing it to close relevance with our era, and the all-too-familiar confinement common to all of us. The world beyond the river is depicted as a scary, dangerous place that presses at the edges of their small existence, serving as a further reminder that we are living in an increasingly atomised age—an era of isolationism between nations sparked by telltale international shifts to the political right, along with increasingly popular feelings amongst world leaders that their ‘country is an island’—catalysed by COVID.

In the ‘territory,’ the suspicion of outsiders is overarching, echoing the eagerness of some to designate certain groups as responsible for their hardships. Half-truths and disinformation are rife; neighbours judge neighbours, and people are cast out for reasons as trivial as having red hair or failing to lose their milk teeth. The setting—dense fog followed by blazing heat in an indiscernible survivalist purgatory—only adds to the novel’s cloying nature. Reading this during quarantine felt akin to falling through the looking glass into a world only slightly more absurd than our own.

Helene Bukowski’s debut is, however, difficult to categorise. In some ways, it is a traditional survivalist novel; the narrator rears rabbits, plants potatoes, makes her own soap. Yet in other ways, this book’s eccentricities combine to form a work that is singularly strange: its chapters are inconsistent, the narrator is highly unreliable, and the reader is left with the feeling that everything is distinctly off-kilter, wondering if anything described is even ‘real.’ The prose reads dreamlike and topsy-turvy, delineating the surreal world that tends to form in the individual’s mind when closed in a bubble of one’s own consciousness. Edith never seems to eat; instead, she is always painting her lips a new colour, lying in the bath for hours or days on end, and wearing a black rabbit skin coat in summer. She feeds her dogs tree bark. To use the vocabulary of Stranger Things, it’s as though they are stuck in the ‘Upside Down.’

In lieu of explanation, Bukowski zeroes in on the immersion in the story’s present. I wondered why society had collapsed—why those who founded the territory fled over the bridge and then blew it up behind them. I wondered where Edith came from, why the trees don’t fruit and the rabbits die. The deeper warning about the imminent climate emergency we are all facing is prevalent, visceral through the book’s eerie atmosphere, but Bukowski does not easily offer up the answers. One is not meant to understand or feel that there is some inner logic driving the book; we see the world through Skalde’s eyes, and she is just as much at a loss as we are. The novel is short as well as labyrinthine, its short chapters creating an almost breathless reading experience.

In a strikingly pared-back style, the fragmentation of this novel also adds to its mystery. Some chapters are no more than short scraps of memory. Time doesn’t seem to move in any linear way. Skalde seems to speak directly through the reader via the medium of cryptic notes written to herself, which stand out from the page, rendered in block capitals. These sections offered a particular literary pleasure, and translator Jen Calleja constructs them with a beautiful cadence in English.

HOW LONG CAN I STAND UPRIGHT WHEN HOLDING UP MY OWN BODY BRINGS ME TO MY KNEES TWICE AS HARD

And elsewhere:

I DREAMED THE SMELL OF GUNPOWDER. THE LAND HAS BEEN LEFT FULL OF HOLES. THESE VOIDS ARE MY DOWNFALL.

This book isn’t for the fainthearted, nor is it meant to comfort someone looking for an uplifting message through our panicked, desperate journey in an age of environmental devastation. Similar to Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Bukowski operates in darkness and heaviness in order to throw light on the worst facets of the human condition—fear, hatred, mistrust, suspicion, selfishness and neglect. Though there are flashes of violence, the novel is instead harrowing on a more psychological level, with one of the most foremost tragedies being the broken relationship between Skalde and her mother Edith. The inexplicable arrival of Meisis tests their loyalties as Edith plays mind games, ignoring and then favouring Meisis over Skalde. Meanwhile, in a world ruled by secrets and suspicion, their small society shuns Meisis as an outsider, initiating a campaign of slowly increasing terror and intimidation against the household.

When Edith, Meisis, and Skalde become the town’s scapegoats, one is reminded of the human desire to impose meaning on madness; we want to find an easy solution, to make it make sense. Someone or something has to be to blame. But prejudice and finger-pointing only ever serve to endanger us further and tear us further apart. Milk Teeth is a novel with a lingering taste, one that weighs on the soul. It asks introspection of us, drawing attention to the cataclysms that daunt our own world even through the imagined, fictive realm. It advocates for responsibility instead of blindness, knowledge instead of ignorance, and in the realisation of the fact that there may no longer be easy answers for our problems, it holds up a mirror so that we may confront our worst instincts.

Anna Rumsby is an MA literary translation student at the University of East Anglia. She also teaches English as a foreign language, writes poetry and historical fiction for her blog, and volunteers for the educational arm at Asymptote. She has translated and commented on extracts from Die zehnte Muse as part of her master’s dissertation.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: