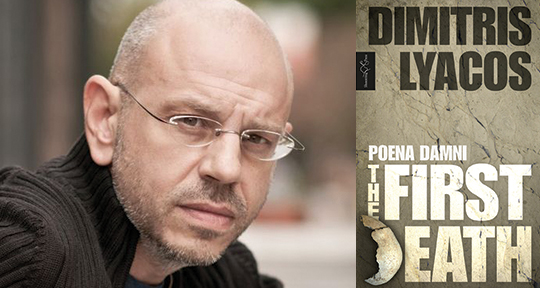

How did a book of Greek poetry become one of the most-discussed and most-lauded pieces of contemporary European literature? Garrett Phelps, Assistant Managing Editor at Asymptote, explains what makes Dimitris Lyacos’ Poena Damni trilogy is so unusual—and so difficult to describe.

Late last year, Shoestring Press published a complete edition of Dimitris Lyacos’ Poena Damni trilogy, translated into English from a newly revised text. Not long after the first volume appeared in 2009, the work became the subject of near-unanimous praise. Fastforward about a decade and it’s widely acknowledged as a crucial addition to the literary canon, the strongest signs being its frequent inclusion in university curricula and its reputation in high circles as a masterwork, a post-modern epic, and a dystopian allegory for the cultural collapse of the West, whose legacy is only despair and rubble and war. Translations into French, English, and German have made it one of the most reviewed works of contemporary European literature, which is rare for any book of poetry and especially one written in Greek. That it’s a masterwork, or at least really near being one, is true. I gathered as much after my first encounter with it a few years ago, when Asymptote featured an extract from Shorsha Sullivan’s translation of Z213: Exit. It floored me back then and still does now.

I’m thankful that I read it before looking at anyone else’s thoughts, because the label “post-modern epic” is misleading, useful only for jacket copy. It reminds me of somebody like Umberto Eco, whose novels are long and fussy, and more about literature itself than that other rich wellspring known as real life. Dimitris Lyacos’ trilogy is definitely not that: whatever runs through its heart is too raw. Other postmodernists with actual talent, like Kathy Acker, are also a very different cut of writer. They tend to deal with ubiquitous cultural products—e.g., movies, music, targeted ad copy, the novel—whose influence pervades, or even dictates, modernity. Their work is heavy on pastiche and ready to relate, sometimes in a single breath, subjects as disparate as Nascar and archaic Greek poetry. Lyacos shares their skepticism of reigning cultural myths, although for him they’re free from the baggage of ideology, manifest destiny, and sense of self. Instead, myths revert to their most embryonic forms, such as the Homeric journey, leading some critics to argue that Poena Damni is in fact more modernist than post-modern. They’re right, too, but the claim sounds so dry when read aloud that I’ve already lost interest. Anxiety about missing the point usually means literature is doing its job.

We are heading there all together, with the train shifting the light and playing with it, the light shifting and playing over a thing that is stealing away. That changes form, a surface in motion. And the road opens, as we approach the road opens up a new road, for us not to be forced to a stop, a door is constantly opening in front of us. We shall never find it in front of us closed, shall never stop, never knock, no one will open for us. We shall never take hold of the skein uncoiling. It will coil and uncoil its edges before us, we will keep seeing it, a dark sign far away ahead.

This passage from Z213: Exit is a good example of Lyacos’ style, but any random sample would do. He sets the stage with a few drab landmarks, such as train, road, door. The poetry is repetitive and stark and heavily monosyllabic, which is why it’s such a pain to describe, especially if you don’t have an hermetic knowledge of things like origin myths or Catholic teleology. How do you talk about it? Adjectives close at hand, like bleak or minimal, feel cheap, and I’ve already exhausted half of them anyway. Most readers, even educated or half-educated ones like me, tend to talk circles around his writing, since it’s easier to identify everything it isn’t than to make an actual point. Another bad habit is bringing up Lyacos’ background in analytic philosophy (a field that’s famous for being complicated) as code for saying his poetry is extraordinarily difficult, which forfeits any responsibility to say something further.

Lyacos does avoid a lot of indulgences common to hyper-educated poets, such as writing books packed with explicit references to other books. There’s a scattering of Biblical quotes, and the New Testament influenced the thin perimeter of a plot. Otherwise, the intertextuality is covert. Questions about if, how, and to what extent Poena Damni uses the canon are a fetish for some critics, who have already unearthed Samuel Beckett, Odysseus, Jesus Christ, the Tanakh, Kafka’s The Castle, Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, and alleged proof that the author is a Christian apologist. Unfortunately, most literary interpretation is farfetched. Anybody convinced Don Quixote is a veiled treatise on Plato, or Cartesian dualism, or the European spice trade is as delusional as a religious fanatic who sees Christ’s visage on a burnt piece of toast. Only Dante could pack the wealth of an entire library, religion, or history into a stanza, and expecting this of any other writer, past or present, is a bit much. Lyacos gives us plenty to unpack, but I doubt we’re supposed to add extra frills. The vocabulary is strict for a reason and added color is rare, leaving much of the illustrative work to poetic form and not narrative. Words break down, they reconfigure, they slip into different tongues. Meticulous care for a written surface always pays off. This is one literary rule actually worth following, and also the last to remain when you reject the usual ways of setting a scene.

Tracking without traces of those searching for me of those I seek. One more. The voltage sags for a while the screen signal is lost, black and white, coloured, black and white, wave on the opposite wall. Of a storm. Without voice m ind ifthereis music that covers. The lights fail for a while, only a while, a piece covers, you drink, mutter je creuserai la terre jusqu’apres ma mort pour couvrir ton corps d’or et de lumiere to cover your body devenir l’ombre de ton ombre l’ombre de ton chien, rain, you drink again, rain. Send a raven to check if it has dried up somewhere. Prelude for what is awaiting you, their lips following on. Should music stop we would be suddenly heard. Chorus of stutterers.

The overall effect is precarious, and every step forward is blind. Our job is to tread with care and hopefully not fall through the floorboards. Samuel Beckett comparisons are typical and not wrong either, although Lyacos makes even him feel florid at times. Tragedy does play a role in the poem as fundamental as myth, which is fitting for an art form devoted the idea of sightlessness and tied to earlier public rituals, such as symbolic bonfires and sacrifice. Human conditions don’t get any more basic than in Poena Damni. It’s a Euclidean landscape, stripped down and elementary, where pathologies are no more than their root-cause and desire is literally having to feel around in the dark: “I didn’t know where you were / I was going down below / a corridor downwards / stairs. I was feeling with my hands / on the wall / like a face.”

Dimitris Lyacos’ trilogy is a blank screen onto which readers will project whatever they want. This is always easy bait for critics, who like the biggest possible range of readings to shrink the odds of being called a charlatan. However, I can’t fault anyone who grabs at the nearest buoy, because there’s no choice with poetry this inhospitable. You do what you can with what you have, or keep quiet. Figuring out what to say is difficult and also a far worse problem than not actually having anything. It feels like trying to scream while gagged.

Dimitris Lyacos is the author of the Poena Damni trilogy (Z213: EXIT, With the People from the Bridge, and The First Death). The work in its current form developed as a work-in-progress over the course of thirty years with subsequent editions and excerpts appearing in journals around the world, as well as in dialogue with a diverse range of sister projects it inspired—drama, contemporary dance, video art, sculpture installations, photography, opera, and contemporary music. So far translated into six major languages and performed worldwide, Poena Damni is the most widely reviewed Greek literary work of the past decades and Z213: EXIT one of the best-selling books of contemporary Greek poetry in English translation.

Garrett Phelps is an Assistant Managing Editor at Asymptote. He lives in London.

*****

Read more essays on the Asymptote blog: