Moving Parts, our September Asymptote Book Club selection, is the second book-length English translation of Prabda Yoon’s work, but perhaps the first book (in any genre) ever to culminate in what our reviewer describes as one of life’s “most seductive question[s]: is it a sadder thing to throw oneself unnoticed from the top of a building or to live out one’s days without a functioning butt plug?”

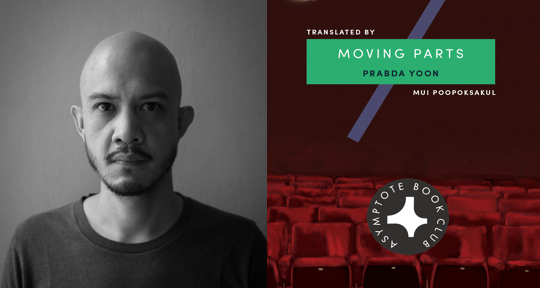

In addition to translating A Clockwork Orange and Lolita into Thai, Prabda Yoon has, according to Words Without Borders, “popularized postmodern narrative techniques in contemporary Thai literature.” Bringing Prabda Yoon’s work into English (together with Tilted Axis), Mui Poopoksakul demonstrates a “facility for translating puns” and delivers one of this year’s must-read short story collections. We’re excited to be sharing it with our subscribers in the USA, Canada, and the UK.

If you’d like to receive next month’s Asymptote Book Club pick, all the necessary information is available on our official Book Club page. Current subscribers can join the discussion on Moving Parts, and each of our nine previous titles, through our facebook group.

Moving Parts by Prabda Yoon, translated from the Thai by Mui Poopoksakul, Tilted Axis, 2018

Reviewed by Lindsay Semel

Prabda Yoon’s short story collection Moving Parts, translated from the Thai by Mui Poopoksakul, dismembers feelings like shame, love, boredom, hope, and disappointment via a cast of Bangkokians ranging from the high elite to the marginal to the very young. These grotesque vignettes speed by, leaving dead bodies, broken glass, weeping dickless men, and floating transvestites in their wake. Poopoksakul captures the playful aurality of Yoon’s writing, balancing the morbid content with levity.

Each story explores a deeply personal anecdote by locating the emotion of it in a particular body part. By anatomizing a psychological phenomenon, the reader can connect with the character physically, not just empathetically. The onomatopoeic vocabulary complements the sensation of experiencing the text in the body. “The Yucking Finger,” at the very beginning of the collection, is a great example. The story essentializes the protagonist’s sense of failure, childhood trauma, and lingering certainty that he’s made all the wrong choices in his life into his one pointer finger which, when it disapproves of him, says “yuck.” More sweetly, in “New Hand” (the title of which demonstrates Poopoksakul’s facility with translating puns), a young boy asks to hold the hand of the first girl he likes. She agrees, he takes her hand, and she runs off, leaving the hand behind with him. He brings her hand home to his family, and we learn that he must court the girl by looking after it. All the sweet apprehension and reluctant hope of first love is concentrated in the hand.

The text gracefully renders the tone and dialogue of people from every corner of Bangkok society. BC became rich and famous heading up a company which invented robot hearts that extend the owner’s lifetime by decades (prohibitively expensive to all but the very wealthy). Mantique, a trans-woman, contemplates the least icky, least terrifying way to commit suicide while referring to herself always by her name, never with pronouns. Two different teenage girls feel ashamed for exposing older men’s missing body parts, leaving one crying and one laughing.

Amidst the excruciating hilarity, moments of sincerity offer sober ‘so what’s. As his teacher berates him for his poor algebra, a schoolboy muses, “Just let X be X. Why is it that when you come across an X, you have to insist on knowing what number it really signifies?” About a pink motel called Paradise Lots: “Here was proof that free knowledge could be found anywhere, even above the door to a whorehouse . . . Whoever saw it as a den of illegality clearly hadn’t been enlightened to the fact that all eternal truths in human life were illicit.” But perhaps it’s the very last story that epitomizes Yoon’s skill for finding truth at the intersection of the absurd and the morbid—and leaves the reader with the most seductive question: is it a sadder thing to throw oneself unnoticed from the top of a building or to live out one’s days without a functioning butt plug?

Lindsay Semel is an Assistant Editor for Asymptote. She holds a BA in Comparative Literature and works as a freelance editor from her home on a farm in Northern Portugal.

*****

Read more about the Asymptote Book Club on the blog: