In 1941, Moïse Yehouessi was called to war. A young man from Benin, he’d studied at William Ponty, a military school housed in a old fortress about twenty miles east of Dakar, in Senegal. Yehouessi fought on France’s side against the Axis powers in World War II. After the war, he immigrated to France, swayed by the propaganda promise of affirmative reception within France.

Three decades later, in December 2015, I sat talking to his granddaughter over Skype. “He was treated like shit,” said Mawena suddenly, from her Paris apartment. France did indeed see a rise in immigration after WWII, from all over Africa. Take, for instance, the thousands of Algerian pieds noirs who fled to France at the end of the Algerian War. It didn’t take long for internal tensions to emerge in France between the nation’s French-Algerians and the larger French populace. In James Markham’s 1988 New York Times article, “For Pieds-Noirs, the Anger Ensues,” former French prime minister Jacques Chirac is reported as saying, “To reconcile France with its colonial past is to reconcile France with itself. […] As a lieutenant in Algeria, I did my duty. I shared your hopes and your agonies, and understood your élan.” The last word, élan, struck me as glib.

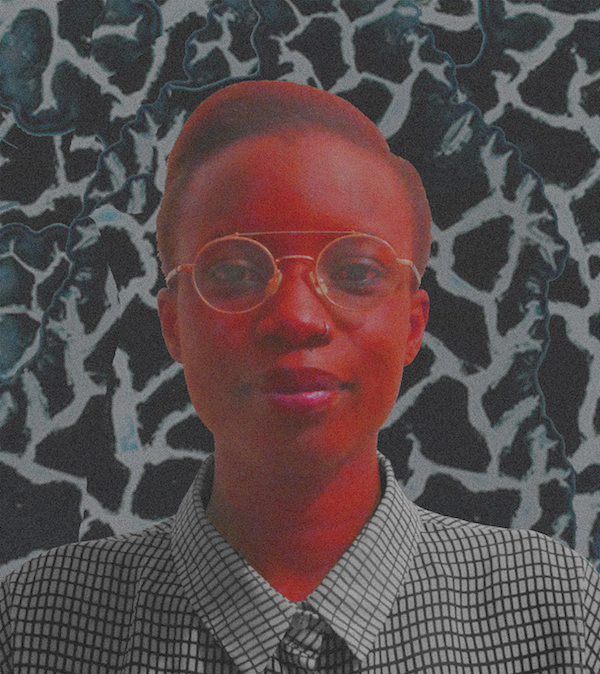

“There is this big crisis in France regarding the national identity,” said Mawena. She held a cigarette in her hand. Mawena acts as the Executive Director of Black(s) to the Future, an Afrofuturist arts organization whose website is a transmedia platform, featuring massive online open courses, mixtapes, artist collaborations, and interviews. A few weeks earlier, Mawena had just finished a three-part interview with Mark Dery, the author often credited with the coining of the term, “Afrofuturism.”

I’d always had my reservations about the hubbub surrounding Dery, but Mawena’s interview re-sparked my interest in him. Mawena as an interviewer was tough and direct, asking complex multi-part questions while Dery’s tone was simultaneously cutting and unhurried. Toward the end of the third interview, Dery said, “Afrofuturism reboots our historical memory, a radical act in America, a country that prefers to sweep its historical horrors under the rug.”

“I think it’s just a matter of waves,” said Mawena, referring to the period directly after WWII when the pieds noirs and other African immigrants struggle to find acceptance in France. She pointed out that, before WWII, the Italians had been the nation’s ‘problematic’ immigrants du jour. Robin Cohen writes in The Cambridge Survey of World Migration, “As regards the Italians, the mass influx of the years 1880 to 1930 was just one in a whole cycle of migrations which had been in progress since antiquity (or it could be said, since prehistory). […] It is now estimated that about 5 million French nationals are of Italian origin if their parentage is retraced over three generations.” Mawena estimated that it took about three generations for a new immigrant population become properly integrated into the rhetorics of French nationality. In other words, three generations as the amount of time it takes for an Italian immigrant, for example, in France to become nominally “French,” or even “French-Italian.”

Naturally, integration functions somewhat differently for African-descended immigrants, whose very appearance seems to reify a perpetual foreignness. Modern day French citizens who are descended from African immigrants are still likely to be called “African” in France, and not “French-African,” Mawena elaborated. This struck me. I found myself saying, “In the States, when we think about immigration, we don’t think about Black Americans. That immigration was long ago enough.” But even now, I’m not sure I was right.

Both France’s de facto and de jure adoption of Black migrants have had impacts on Black artists working in France. Mawena studied cultural management, the American equivalent of which, I believe, is arts administration. “In France, we have this real esteem for cultural institutional projects,” she added. Such cultural projects usually also contain some component of State support. For example, I.M. Pei’s La Grand Louvre was commissioned by former President François Mitterand, the Musée D’orsay by former President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, and in 2006, President Jacques Chirac (the former Prime Minister quoted above in a statement to France’s pieds noirs) unveiled the Musée du quai Branly, named after French physicist Éduoard Branly.

The Musée du quai Branly came up when I asked Mawena about arts institutions in France showing work by Black artists. The museum boasts of 70,000 objects from the sub-Sahara in its Africa collections. “Who is their audience?” I asked Mawena. “Exactly!” she replied, laughing. Mawena explained that there wasn’t much ‘hype’ surrounding contemporary Black art in France. As a result, since its launching, Black(s) to the Future has had to overcome a few hurdles garnering support from France’s larger cultural institutions. “It’s hard to make people understand that we’re not working for a niche,” said Mawena.

She attributed the difficulty to the tendency in French national rhetoric towards humanism, saying that artistic projects that seem to value one community over the others don’t often find many backers. Of course, Black(s) to the Future isn’t at all about achieving Black supremacy and is every bit about counteracting the pigeonholing of Black art and Black artists in Western arts discourses—this very pigeonholing, I might add, being the reason support has been difficult to come by.

Despite this, Black(s) to the Future has thrived and Mawena still believes that communication is the best weapon of our time, pointing out that the speed and variousness of digital communications allows everyone to find their audience. She insists on an approach to Afrofuturism that centers upon the the actual futures of Black people and is decidedly less enthusiastic about reifying Afrofuturism’s historic connection to science fiction. Most recently, she facilitated an interdisciplinary collaboration between American author Ytasha Womack and French painter Yves Murangwa.

After about an hour, Mawena revealed to me that she thought she might cry once our interview was over. It had been a long but engaging conversation, each of us having shared various parts of our personal migration histories with the other. We were both, admittedly, a bit teary-eyed. Perhaps sensing a drop in morale, Mawena said, “We have to be faithful. Ok, so the future’s not going to be bright, but it can be so… I don’t know!” She smiled at me. Mawena is an optimist and talking to her, I felt like one too.

*****

Anaïs Duplan‘s writing has appeared in Hyperallergic,[PANK], Birdfeast, Phantom Limb, and other publications. She is a head curator at The Spacesuits and an MFA candidate at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.