József Szabó (technical manager): Of the books I’ve read during the past few months, Hans Erich Nossack’s An Offering for the Dead (trans. Neugroschel) has become a book I highly regard. It was my slow but steady mining of the out-of-print Eridanos Library series that led me to this short novel, whose not-so-familiar author stood out from the others in the set, such as: Heimito von Doderer, Michel Leiris, Piñera, Klossowski, Landolfi, Akutagawa, Savinio, Musil.

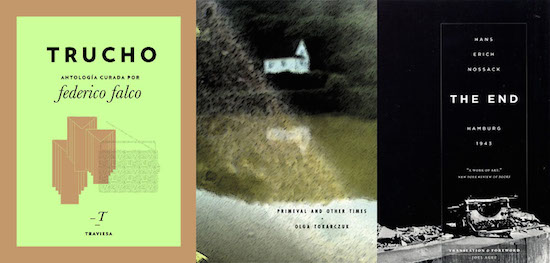

An Offering, stylistically, reads as if (Hamburger’s) Celan wrote a ~120-page surrealistic threnody in prose for European victims of a WWII bombing. Readers expecting a plot will find, instead, a vision: of a rainy, war-ruined city, where everyone is dead; only ghosts (lemures) remain, pacing around the desolation, idling in a conflation of memories, nightmares, myths. The narrator gives us a somnambulistic tour of this ghost-world. Unfortunately, all of Nossack’s fiction looks to be out of print in English translation, but an essay-memoir, Der Untergang, published as The End: Hamburg 1943 (The University of Chicago Press, 2004; trans. Joel Agee), is readily available for purchase online. An excerpt, found here, makes it clear how such a ghost-world was dirempted into existence.

Some of my other notable recent reads include:

Juan García Ponce’s Encounters (Eridanos Press, 1989; trans. Helen Lane), which is reverently introduced by Octavio Paz, and consists of four short stories, with the shortest being six pages and the longest just going over fifty. After reading this collection, I see García Ponce as a Euclidean geometrician who uses people, places, and things as points (“A point is that which has no part”), and then uses a narrative to form the connecting lines: the enclosed, unsaid space of the resulting polyhedron represents a highly nuanced, evanescent mode of being. His mathematically simplified stories reveal—hold steady—these complex ways of encountering the world. With that said, though they are quite different writers, Encounters had me thinking back to the complicated structure of the nostalgia in Felisberto Hernández’s “Just Before Falling Asleep” (trans. Luis Harss).

Marian Engel’s first novel No Clouds of Glory (1968) was later reissued with the title Engel originally wanted: Sarah Bastard’s Notebook. And it is certainly the better title, for there is now no risk of Graham Greene obfuscating the first impression; instead, it became clearer to me that Engel had Rilke’s Malte Laurids Brigge in her (night) sky. As such, her novel is a Künstlerroman or, better, an Akademikerroman: the growth of an academic into maturity, where “maturity” is another way of saying “a disdain for academia.” Unlike in Bear (1976), the novel she is (in)famous for, Notebook is written in melopoetic, erudite prose that sprints and leaps, reading like a combination of Grace Paley and Renata Adler. For her stylistic achievements, Engel rightfully belongs with two other Canadian #failedintellectuals: Leonard Cohen (Beautiful Losers, 1966) and Graeme Gibson (Five Legs, 1969; Communion, 1971).

Ágnes Orzóy (editor-at-large, Hungary): It so happens that my latest favorite books are all by Central European authors, and are all about displacement, in one way or another.

Hungarian author Árpád Kun’s 2013 Boldog észak (Happy North) is the story of a certain Aimé Billion, who starts off from Benin, West Africa, at the age of 38, and ends up in Norway, where he becomes a home carer. What immediately strikes the reader is that whatever Kun describes, from voodoo rituals to Norwegian society and landscapes to old and infirm bodies, he characterizes it with a rare combination of empathy, openness, and sober precision. Aimé Billion is an eternal outsider who, when confronted with a host of challenges and an extreme variety of circumstances, charts them all with the same affability, acceptance, and curiosity.

All This Belongs To Me (2002, Eng. 2009) by Czech writer Petra Hůlová is narrated by five female members of the same Mongolian family. What I found strikingly beautiful in the book is the tension between the foreignness of the narrative world and the familiarity of the conflicts that determine the women’s choices. Hůlová, who studied Mongolian in Prague and wrote this novel at the age of 23, decided to foreground a sense of alienation by using a number of Mongolian expressions. The English translation by Alex Zucker was published by Northwestern University Press as part of their Writings from an Unbound Europe series, a terrific series of books from ex-communist countries, now defunct, largely due to the fact that our region does not seem to be as sexy as it was ten or twenty years ago.

In Primeval and Other Times (1996, Eng. 2010), Polish novelist Olga Tokarczuk takes a concrete time and place, a Polish village through the 20th century, and elevates it to a mythical plane. One by one, the horrible events of the previous century inexorably visit the oneiric world of the village called Primeval, leaving their scars on people, land, animals, and objects. Tokarczuk describes them all with an empathic, healing, and animistic touch, inscribing a ballad of the inner life of the village. The English translation by Antonia Lloyd-Jones was published by the excellent Prague-based press, Twisted Spoon, and is a major achievement.

Frances Riddle (editor-at-large, Argentina): The Argentine colloquial term “trucho” could be used to describe the pair of “Addibas” sneakers in the dark corner of a flea market; it’s the “Sonya” headphones bought from a blanket on the sidewalk. If “trucho” is a knockoff, a poor copy, passed off as an original, this anthology is the antithesis of its title. Trucho, (Knockoff) begins with Federico Falco’s fine-grained explanation of the meaning and origin of the word that gives the book its name.

In Diego Zúñiga’s short story, “Omega,” the action hinges around a watch left behind by an absent father. This is not just any watch, but a “Moonwatch,” that promises to keep functioning in zero gravity and other extreme conditions in which a person would probably never find themselves. “Las Mañanitas” by Federico Guzmán Rubio peeks in on a dinner party at the house of a nervous Mexican couple. With their neighbor as a paid coach, the family projects a watered-down version of their Mexican identities, Americanizing their habits in hopes of bonding with the boss to land a big promotion.

“La marca” (“The label”) by Javier González divides the world into two groups: those who can afford to wear the label and those who can’t. The label’s brilliant designer, flawless copier of the foremost European fashions, regularly visits shops to ensure that employees maintain the label’s image. Hernan Vanoli’s story “Dos sables laser” (“Two Lightsabers”) is the creepiest, most thought-provoking of the four stories and my favorite. Vanoli constructs an elastic reality where a clone, responsible for all digital correspondence, begins to take over the protagonists’ real world activities.

Trucho, one of Traviesa’s several short anthologies, gives us four highly original and engaging stories from four exciting young Latin American writers, and can be read in English translation or in Spanish.