When Indian author Sampurna Chatterji was growing up, she lived between several languages. Her father taught English, while her mother taught Bengali. In Chatterji’s own schooling, the instructional language was English, but she also learned Hindi and Sanskrit.

“All this creates a sort of strange cacophony in the head,” Chatterji said at a professional seminar at this year’s Abu Dhabi International Book Fair, held from April 30 to May 5.

But this “cacophony” also creates wonderful opportunities for linguistic connections. As she developed as a writer, Chatterji decided not to write in Bengali. “The burden of being Bengali was too much for me,” she said. Her teenage rebellion was not to go off and smoke, but to write in English.

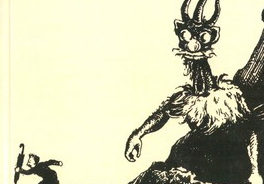

So she published collections of poetry and novels in English. But she continued to have lines of Sukumar Ray’s Bengali poetry knocking about in her head. Ray wrote “this incredible nonsense poetry and prose,” Chatterji said. Ray’s poetry was deeply influenced by Lewis Carroll and “difficult to explain, but you can feel it in your bones.”

Others had understood the importance of Ray’s poetry, and there was an English translation of Ray’s poetry that was “very accurate,” Chatterji said, but it utterly lacked the joy she remembered. She wanted to see if she could re-enact the joy she’d felt when listening to and reading the poems, so she thought: “Let me see if I can do it.”

“It was a moment of great hubris, because I thought I could” translate the poetry, Chatterji said. Whereas “the Bengali literary mafia would say: ‘This is untranslatable.'”

Ultimately, Chatterji decided that “it seemed to me an awful shame that any Indian child who did not know Bengali should be deprived of this plentitude.”

In English, this collection of poems became Wordygurdyboom, and Chatterji said she really had to exhort her linguistic muscles, particularly in translating the Bangla sound words. “Because in Bangla, we have sound words for almost everything.”

“I had to really push myself,” she said, also noting that Ray’s “rhyming is impeccable but it sounds like conversation. I had to work very hard.”

Although a good chunk of Bengali literature “is traveling into English thanks to many people in the publishing world being Bengali,” Chatterji said, this is not true of many languages.

Alexandra Büchler of Literature Across Frontiers, who also spoke at the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair, noted that one of the major obstacles in translating new material is the money involved. “There is very little support available, and when publishers apply for grants, for instance when they want to publish books translated from European languages, [the granting bodies] usually would go for adult novels. It’s still quite rare” for the money to go to children’s books.

Even rarer is that translation funding would go to beautiful nonsense poems. And yet how important these nonsense poems can be! Büchler noted, in conversation, that when she’s asked to speak in Czechoslovakian, her mother tongue, what pops into mind is a Czech translation of Lewis Carroll’s poetry.

Humphrey Davies was once asked, at a talk at the American University in Cairo, whether he thought there were “untranslatable texts.” While Davies hasn’t translated any children’s nonsense poetry from the Arabic, his work on Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq’s Leg over Leg certainly faced similar difficulties. At the talk, Davies suggested that there are only texts “that haven’t found their translator yet.”

***

M. Lynx Qualey lives with three child-readers of ever-increasing ages. She has a particular love for Arabic children’s literature, but is broadly interested in how narratives for children are shaped around the world. She blogs daily at http://www.arablit.org.