“Poetry needs experiment, philosophical reflection on its own material, rebellion, seeing itself as a task for readers,” argued Piotr Śliwiński in his 2002 overview of contemporary Polish poetry, Adventures with Freedom. “In other words, it needs Karpowiczs. Especially Polish poetry, dominated over the last two decades by Miłosz and Herbert.” As a translator, I often think of Śliwiński’s diagnosis, particularly when I need to disappoint my interlocutors with the news that I don’t translate Herbert, Miłosz or Szymborska. I don’t have to – they are synonymous with Polish poetry in English. But Karpowicz? How to explain, then, what poetry needs, if this name hardly functions outside Poland? Another challenge: how to present a poet Karpowicz tried to promote, both in the US and in Poland? If only I could say, “Krystyna Miłobędzka is one of the Karpowiczs…”

In 2011, while I was working on Nothing More, my translations of Miłobędzka, an amazing correspondence between her and Karpowicz, who died in 2005, appeared in print. To write an essay accompanying eleven English versions of her poems (published in the last issue of the Chicago-based journal 2B, 1999), he identified 202 themes in her poetry and asked her 29 questions. I would like to quote two of Miłobędzka’s answers, both to share this exchange and to introduce the poet whose texts, in Karpowicz’s opinion, “are the realm of the incomplete sentence; in spite of appearances, they have a more aggressive structure (form) than the realm of complete sentences written, for instance, by Wisława Szymborska.”

Justifying her preference for the fragmentary, Miłobędzka explains: “I can’t quite stand the distance between I live and I speak—they never happen simultaneously. At first I have this wordless text, everything moves there, sparkles; when said (written), it stiffens. Dies. ‘Speech a cracked glass’ … ‘Words want to live, not to speak,’ that’s my usual problem. Banal—but coping with it in various ways I’ve managed to write a couple of texts.” Such verbal scraps, jottings (as she refers to her poems) attempt to convey Miłobędzka’s conviction that we are our vanishing.

where do who

do I before I begin

who first, who mine, who best

which of my selves shall I leave you for good

why the one laughing with plaits out of breath

which of my selves shall I leave you from which deep drawer

in which photograph developed but blurred

the one older by you, the one silent about you

the one at the last minute running up to here

a face among faces, moved in a bright streak

with the eyebrows raised high

this astonishment everywhere out of place

on the shore of the sea, verge of the woods, edge of the bed

tip of the tongue

Miłobędzka’s deliberately unpolished accounts of our being in constant movement, jotted down in “the inseparable entanglement of life and language,” centre on familiar details: woman as daughter, lover, wife, mother. Asked by Karpowicz about her efforts to construct “home” in language, Miłobędzka answers: “That’s a rather pathetic dream – a house from words. It can’t be built out of yesterday, or today, or tomorrow. The dream of the writer who would like to repay her debt to her parents for the real house from brick. ‘Try’—there’s so much faith in it, and so much resignation. But we keep trying. … Only such attempts—to make from language something stronger than language – have a little permanence.”

maybe she has no one to say herself to loud enough with this long-recalled

stutter in the most unexpected places in the same well expected moment?

and how to stand it even if someone was more patient than a table?

to say or to vouchsafe at least the beginnings of something vital (she hides

minor discoveries at the back of her head)

she is particularly keen on the eyes and the faces the smile of comprehension

in something similar someone similar

… her inconversations she sits with both her hands on the edge of the table

seems to be asleep today she has only bought one bunch of dill

The table, part of home, is also an important point of reference in conversations about Polish poetry. Karpowicz’s essay about Miłobędzka opens with the mention of another poet, representative of the avant-garde, Julian Przyboś (hardly translated into English) and his 1938 poem containing the line: “Strike the table twice and beyond once.” Karpowicz marvels at the giddiness of this lexical and grammatical proposition which transforms the immaterial into wood. Matter and cognitive projection overlap to create what he calls open metaphor, so peculiar to Miłobędzka’s writing.

“Striking beyond, that’s the power of poetry,” claims Wojciech Bonowicz in a conversation published under the title “Praise for Incomprehensible Poetry,” which starts off with the reference to Miłosz’s essay “Against Incomprehensible Poetry.” For Bonowicz, the concept of “incomprehensible poetry” itself highlights the notion of comprehension, fundamental to contemporary poetry. (I would add that comprehension is especially foregrounded in translating.) He defends ambiguity and indefiniteness as his means of writing against language—to strike beyond and hit something that, though not as familiar and concrete as the table, “will still respond with an echo.”

Echoes is Bonowicz’s latest book of poems, characteristically unobvious. Queried about their mysteriousness and, paradoxically, their accessibility, he replies that he favours perceptions that aren’t or can’t become certainties: “such open constructions are the most honest.” Asked about the poet he reads with utmost attention, he names Miłobędzka. Here I present two versions from Echoes to sketch a conversation between Wojciech Bonowicz and Krystyna Miłobędzka, in English translation.

Warszawa

Morning she drinks coffee. Though she doesn’t like it.

She likes fruit though she doesn’t eat it.

She lies down on the floor to force it to move.

The ceiling looks deep into her eyes shakes the lamp.

Until noon she’s reaching equilibrium.

Evening at the same spot under the green quilt

she asks if the deities will do their share of chores:

collect wood cleave meat light a fire.

Contents

Do I speak as if I knew something?

I know nothing.

There’re bright days,

and dark.

I lean forward to look more closely.

What I see

is a face

not yet doused.

Earth sky

and the face

in-between.

—

Publications mentioned:

Tymoteusz Karpowicz, Andrzej Falkiewicz, Krystyna Miłobędzka. 2011. Dwie rozmowy (Oak Park/ Puszczykowo/ Oak Park) (Two Conversations). Ed. Jarosław Borowiec. Wrocław: Biuro Literackie.

Piotr Śliwiński. 2002. Przygody z wolnością: uwagi o poezji współczesnej (Adventures with Freedom: Remarks on Contemporary Poetry). Kraków: Znak.

Wojciech Bonowicz in conversation with Kuba Mikurda (2007) and with Marcin Baran (2013).

—

Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese regularly publishes translations of contemporary Polish poetry in journals and anthologies (they appeared also on the London Underground). She co-edited Carnivorous Boy Carnivorous Bird: Poetry from Poland (2004) and co-wrote Metropoetica. Poetry and Urban Space: Women Writing Cities (2013). Nothing More, her versions from Krystyna Miłobędzka (introduced by Robert Minhinnick), has just been issued by Arc Publications. The Polish focus in the autumn 2013 Modern Poetry in Translation features her translations of Miłobędzka and Bonowicz.

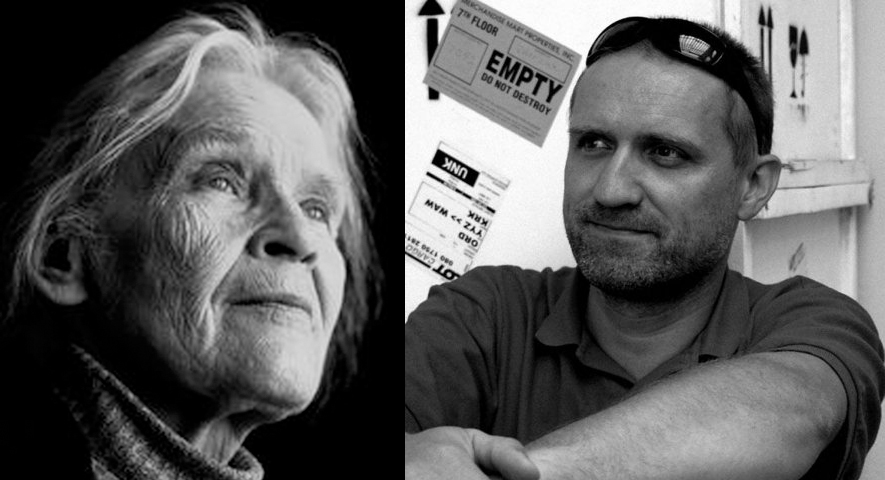

Krystyna Miłobędzka (b.1932) has written plays for children as well as a monograph and a volume of essays on children’s theatre. She is the author of twelve books of poetry. Her collected Zbierane. 1960-2005 (Gathered: 1960-2005) appeared in 2006, and zbierane, gubione (gathered, lost) in 2010. Recipient of numerous awards, she was nominated for the NIKE Prize in 2006 and won the Silesius Award in 2009. In 2013 she was awarded the Silesius for Lifetime Achievement. She lives in Puszczykowo near Poznań, Poland.

Wojciech Bonowicz (b.1967) is a poet, journalist and editor; he writes a column for the weekly Tygodnik Powszechny. He has published six poetry volumes: Pełne morze (High Seas) was awarded the prestigious Gdynia Literary Prize in 2007 and shortlisted for the most important literary award in Poland, the NIKE Prize. His most recent collection is entitled Echa (Echoes; Biuro Literackie, 2013). Bonowicz also writes nonfiction and children’s books. He lives in Kraków, Poland.

Photographs: Bonowicz by Anita Poniklo; Miłobędzka by Elżbieta Lempp.